Recherche

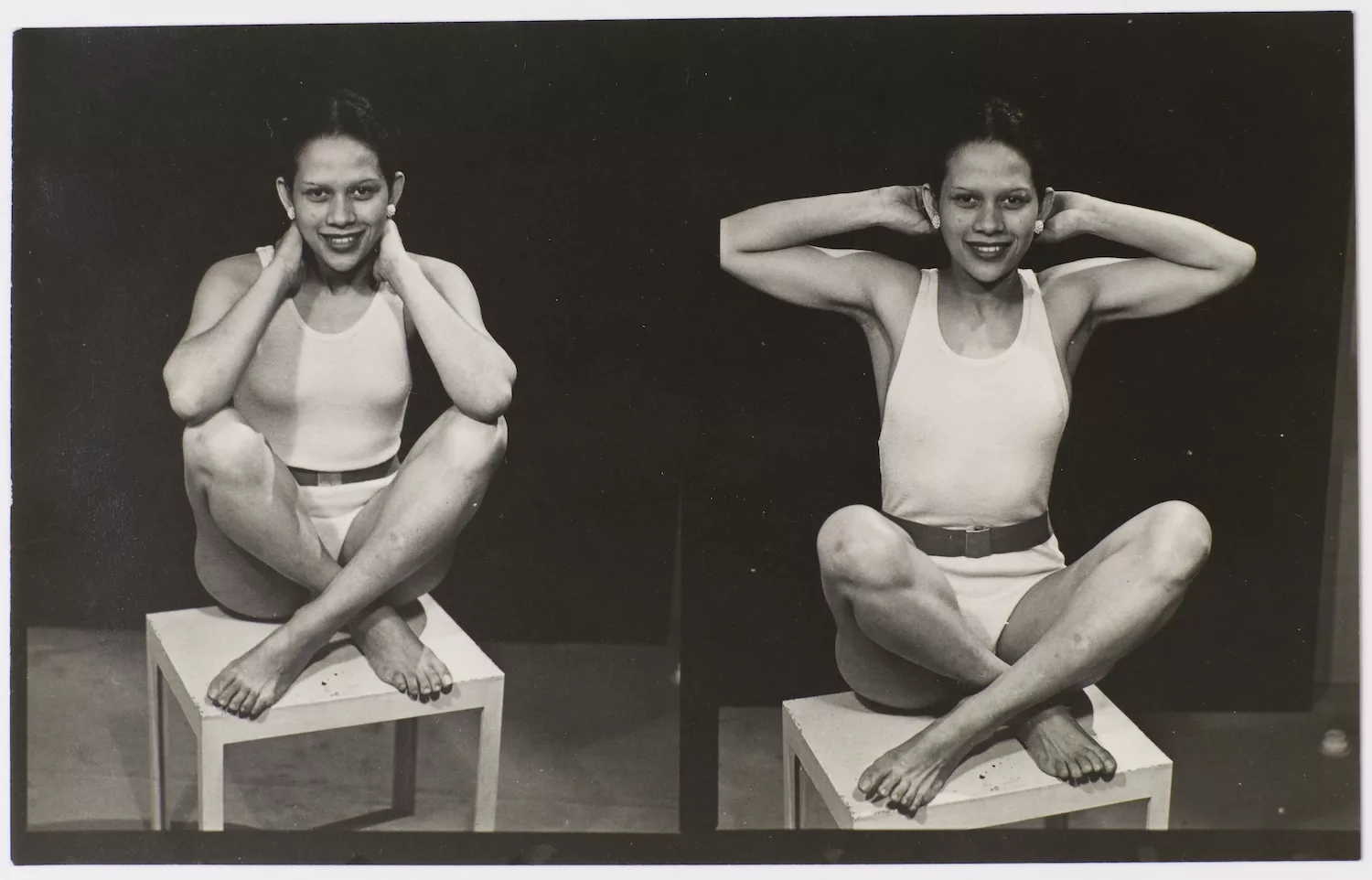

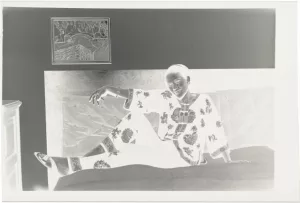

Man Ray, Adrienne Fidelin (deux images), 1937, épreuves gélatino-argentiques, 5,5 x 8,9 cm, Centre Pompidou – Musée national d’art moderne – Centre de création industrielle © Man Ray Trust / ADAGP © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Guy Carrard

Clare Patrick est la lauréate de la deuxième édition du programme Marie-Solanges Apollon porté par AWARE: Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, qui vise à promouvoir la recherche sur les pratiques artistiques transculturelles des artistes femmes d’ascendance africaine, en s’inspirant du concept d’Atlantique noir développé par Paul Gilroy. La publication du texte qui suit a été précédée d’une table ronde organisée le 3 juillet 2025 au centre de documentation d’AWARE, à Montparnasse, réunissant la commissaire d’exposition et chercheuse Claire Tancons, l’artiste sonore et écrivaine Jamika Ajalon, ainsi que Clare Patrick.

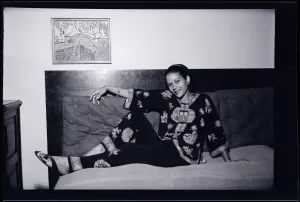

Man Ray, Adrienne Fidelin, vers 1938, 6 x 9 cm, impression gélatino-argentique © Man Ray Trust / ADAGP © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / image Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI

Man Ray, Adrienne Fidelin, vers 1938, 6 x 9 cm, Négatif gélatino-argentique sur support souple nitrate © Man Ray Trust / ADAGP © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / image Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI

Adrienne Fidelin (1915-2004) apparaît dans de nombreuses images, mais ses contributions ont été floutées, recouvertes d’un voile opaque. Artiste de spectacle guadeloupéenne active à Paris dans les années 1930, elle est surtout connue à travers sa relation avec le photographe franco-américain Man Ray (1890-1976). Compagne de ce dernier durant au moins quatre années à partir du milieu des années 1930, elle laisse une empreinte visible dans des centaines d’œuvres et d’écrits de Man Ray et de leurs contemporain·es. Pourtant, les monographies de Man Ray ne lui consacrent rarement plus qu’une note de bas de page et l’on s’est systématiquement moins souvenu d’A. Fidelin que des autres « muses » de l’artiste, Kiki de Montparnasse (1901-1953) et Lee Miller (1907-1977). La présence d’A. Fidelin dans le Paris de l’entre-deux-guerres est rendue visible notamment par les archives de Man Ray, mais est ignorée des récits canoniques (expositions, archives, biographies, catalogues). Ce constat invite à réviser l’historiographie du surréalisme en mettant en lumière les réseaux de l’Atlantique noir, à repenser le rôle du corps et du travail performatif, et à reconsidérer le poids de l’influence socio-culturelle.

In Her Hands : Adrienne Fidelin, performance et fréquences diasporiques — table ronde avec la participation de Claire Tancons, Jamika Ajalon et Clare Patrick, chercheuse en résidence à AWARE. Organisée dans le cadre de la résidence Marie-Solanges Apollon, le 3 juillet 2025. © AWARE : Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions

In Her Hands : Adrienne Fidelin, performance et fréquences diasporiques — table ronde avec la participation de Claire Tancons, Jamika Ajalon et Clare Patrick, chercheuse en résidence à AWARE. Organisée dans le cadre de la résidence Marie-Solanges Apollon, le 3 juillet 2025. © AWARE : Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions

In Her Hands : Adrienne Fidelin, performance et fréquences diasporiques — table ronde avec la participation de Claire Tancons, Jamika Ajalon et Clare Patrick, chercheuse en résidence à AWARE. Organisée dans le cadre de la résidence Marie-Solanges Apollon, le 3 juillet 2025. © AWARE : Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions

La résidence de recherche Marie-Solanges Apollon, qui m’a menée à Paris, s’appuie sur la notion d’Atlantique noir développée par Paul Gilroy. Celle-ci a orienté mes recherches autour des concepts d’interaction transnationale et de migration contrainte, tout en m’amenant à engager un dialogue avec les travaux de Tracy Denean Sharpley-Whiting, Claire Tancons, Ingrid Kummels, Tina Campt et Saidiya Hartman, afin de réfléchir aux interrogations féministes portant sur la présence, l’absence et les processus de « fabrique de soi1 ». La définition de la diaspora par l’historienne de l’art social Petrine Archer-Straw – « une forme discursive liée à la dispersion, à la différence et à la multiplicité2 » – a également enrichi ma manière d’aborder l’imagerie d’A. Fidelin. En considérant sa trajectoire entre la Guadeloupe et la France métropolitaine, ce projet resitue A. Fidelin au sein d’une présence noire transnationale à Paris. L’exploration des dynamiques de déplacement, d’influence et de circulation permet ainsi de considérer son histoire comme une méthode pour élaborer des récits plus nuancés de l’histoire de l’art.

J’aborde cette recherche d’un point de vue curatorial, guidée par des questions et par la quête de connexions. Les pistes émergent dans les interstices : lorsque l’on lit entre les lignes, que l’on décode des lettres-palimpsestes, que l’on prend le silence pour preuve et que l’on comble les lacunes par l’imagination. Il n’existe pas, à ce jour, d’archive institutionnalisée d’A. Fidelin – ses papiers personnels se trouvent plutôt dans des archives familiales ou dans des anecdotes transmises oralement. Dans une démarche transnationale, j’ai suivi sa trace dans le fonds d’archives Man Ray conservé à la bibliothèque Kandinsky du Centre Pompidou, mais aussi au Getty Research Institute, au Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, au Victoria and Albert Museum, à la Tate Britain et à la Farleys House & Gallery – consciente que son image demeure la propriété d’autrui. Ce déplacement fait écho à la formule de Stuart Hall, selon laquelle ce qui est « pensé comme dispersé et fragmenté en vient, paradoxalement, à être représentatif de l’expérience moderne3 ». Son nom apparaît de manière inconstante : Ady, Adrienne, Adie, et parfois Casimir Joseph Adrienne Fidelin. À la bibliothèque Kandinsky, j’ai découvert un document mal classé : une lettre échangée pendant la guerre avec Paul Éluard (1895–1952), incorrectement répertoriée sous le nom de « Fidolin ». Je m’interroge sur le nombre d’autres occasions manquées de retrouver sa trace. Dans une boîte d’archives se trouve le contour de son pied dessiné sur du papier brun ; une autre lettre arbore des lèvres flottantes, rappelant une peinture de Man Ray habituellement associée à L. Miller, ainsi que des croquis de ses chats à signer. Une lettre de Man Ray adressée à A. Fidelin évoque « notre petite maison4 » à Saint-Germain-en-Laye – une demeure habituellement attribuée uniquement à Man Ray dans ses biographies, tandis que les mots-valises ludiques « Manady, Addyman5 » laissent deviner la vie commune bâtie par le couple et l’avenir qu’ils envisageaient ensemble.

Face aux lacunes et aux silences qui entourent A. Fidelin, on réalise que reconsidérer sa personne nécessite de conjurer une présence par l’absence. Elle réapparaît dans des mains dessinées et dans des inscriptions manuelles. Dans ce qui est peut-être l’une des seules descriptions d’A. Fidelin comme figure active, P. Éluard la désigne comme la femme avec des « nuages dans les mains6 ». Les Mains libres (1937) est un projet collaboratif qui réunit P. Éluard et Man Ray et voit le jour lors de l’un des rassemblements d’été des surréalistes – un cercle qui compte aussi Pablo Picasso (1881-1978), Dora Maar (1907-1997), Roland Penrose (1900-1984) et Nusch Éluard (1906-1946), tous·tes apparaissant aux côtés d’A. Fidelin sur plusieurs photographies. Sa présence peut être suivie tout au long de cette collaboration, tant visuellement que dans les descriptions, alors que les hommes échangent dessins et poèmes, déployant ainsi un jeu parent du cadavre exquis. Par la suite, Mary Reynolds (1891-1950) réalise une reliure sur mesure de l’ouvrage, où elle représente une présence-absence des mains à travers des gants cousus sur la couverture. L’un des nombreux dessins qui constituent Les Mains libres, intitulé La Femme au bras cassé, prend la forme conventionnelle d’un portrait d’A. Fidelin. Son visage est représenté de trois quarts, dessiné par des lignes continues, qui tracent de manière minimaliste les contours de ses traits et de ses épaules. En bas à gauche, on peut lire l’inscription « La femme au bras cassé » et, comme dans le prolongement de son épaule ou peut-être de la ligne d’une boucle de cheveux, son nom, « Ady », écrit en miroir. Ses mains n’apparaissent pas dans cette image, pas plus que son bras prétendument cassé.

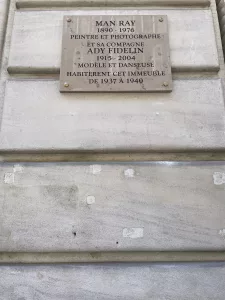

Plaque commémorative en hommage à Adrienne Fidelin et Man Ray, 40 rue Henri Barbusse, Paris, France, 2025 © Clare Patrick

Plaque commémorative en hommage à Adrienne Fidelin et Man Ray, 40 rue Henri Barbusse, Paris, France, 2025 © Clare Patrick

Atelier de Man Ray, 2 bis rue Férou, Paris, France, 2025 © Clare Patrick

En explorant la manière dont les mains des artistes tiennent, façonnent, créent – tout en laissant parfois très peu de traces – j’ai noué des liens avec plusieurs artistes contemporain·es transdisciplinaires. Durant ma résidence à la Villa Vassilieff, j’ai rencontré Jamika Ajalon, Minia Biabiany, Malik Crumpler, Mike Ladd, Attandi Trawalley et Anouchka Agbayissah. J’ai arpenté les Buttes-Chaumont, Montreuil, Saint-Denis, le Père-Lachaise et les berges de la Seine. Curieux·ses des marques et des modes de manifestation, nous avons discuté de la présence, de la fugitivité et de nouvelles formes de mémoire. Ces échanges ont infléchi ma lecture de l’identité d’A. Fidelin, insaisissable, semblable à un nuage, changeante – ouvrant ainsi un cadre d’analyse plus vaste. J’ai suivi les pas des personnalités de Montparnasse, retrouvant chacun des appartements de Man Ray qu’A. Fidelin aurait pu partager avec lui. La proximité des adresses d’autres artistes – Gertrude Stein (1874–1946), P. et N. Éluard, P. Picasso – ainsi que la multitude de bars et de cafés, permet d’imaginer aisément la fréquence de leurs échanges. Les séjours estivaux successifs dans le sud de la France – Mougins, Cannes, Antibes – et même jusqu’en Cornouailles, témoignent d’années d’amitiés au sein du groupe surréaliste. En marchant, je pense à ces amitiés forgées lors de conversations nocturnes, autour d’un déjeuner ou encore d’un verre, et qui traversent des années d’interactions continues.

La vie artistique de A. Fidelin à Paris gravit autour de la danse7, du spectacle, du mouvement surréaliste8 et de son activité de modèle9. Elle arrive à Paris au moment où la biguine10 fait fureur sur la scène florissante du jazz. Son goût pour la scène, dans les clubs de Montparnasse et au Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, est évoqué dans les lettres qu’elle et son mari André Art adressent à Man Ray durant les années 1940 et 195011. Le roman de Gisèle Pineau, Ady, Soleil Noir (2021)12, fabule dans les interstices du savoir historique : loin de se conformer aux codes attendus de la métropole, l’A. Fidelin de G. Pineau s’adonne à la danse et fréquente les cercles artistiques parisiens afin de forger sa propre subjectivité13. Le travail de François Lévy-Kuentz, qui assemble des extraits filmés par Man Ray dans Un été à la Garoupe (2021)14, laisse apparaître un court passage tremblant où l’on distingue une silhouette voilée que je suppose être celle d’A. Fidelin. Elle se meut lentement, tendant les mains vers la caméra. Les lignes de ses paumes ont été noircies à l’encre. Si bref soit-il, ce plan révèle un intérêt pour une performance qui dépasse les clubs pour investir l’espace de l’atelier – une exploration du geste, du voilement et de la création abstraite, en cohérence avec une trajectoire d’expérimentations surréalistes.

Dans Le Discours antillais (1989), Édouard Glissant établit un lien entre collectivité et auctorialité, et en invitant à réfléchir sur le rapport entre récit et individu : il s’agit de considérer comment une communauté influence les individus qui la composent, et réciproquement, comment ces individus participent à façonner la communauté elle-même.15 In fine, on ne peut quantifier l’influence, et la présence est par essence intangible. Au-delà de sa singularité, A. Fidelin donne aux surréalistes accès à un monde au sein duquel ils pourraient n’être, sinon, que des invité·es de passage16 : « Dans les clubs de jazz, les citadins et l’avant-garde pouvaient être en contact physique avec des personnes noires pour donner corps à leurs fantasmes17. » Si l’on élude la présence de A. Fidelin au sein du cercle surréaliste dans ces années, qui sont incontestablement leurs plus transformatrices et leurs plus déterminantes, cela revient à faire fi des influences culturelles et sociales plus étendues qui informent leurs recherches artistiques. Ignorer son rôle clef, c’est donc effacer les interactions intimes qui ont lieu entre les surréalistes et une plus large présence de l’Atlantique noir, dès les premières années de l’entre-deux-guerres, au cœur même de Paris.

Bal Blomet, 33 rue Blomet, Paris, France, 2025 © Clare Patrick

Bal Blomet, 33 rue Blomet, Paris, France, 2025 © Clare Patrick

L’activité publique d’A. Fidelin atteint son apogée juste au moment où la Seconde Guerre mondiale disperse les surréalistes, et où sa relation avec Man Ray est interrompue par l’exil de celui-ci aux États-Unis. Après cette séparation, et bien qu’ils maintiennent une correspondance privée au moins jusqu’en 1961, sa présence est plus difficile à retracer, malgré son décès relativement récent en 200418. Comme l’ont souligné W. Grossman et S. Patterson au fil de leurs recherches consacrées à A. Fidelin, le champ des possibles reste obstinément insaisissable. Enquêter sur une vie apporte tout autant de trouble que de lumière, et il est difficile de quantifier l’influence qu’a pu avoir un individu, même lorsque l’on dispose de sources importantes. Cette difficulté s’accentue, comme l’observe Claire Tancons, lorsque « qui vous pouviez être ne dépendait pas tant de qui vous étiez mais de qui les autres voulaient que vous soyez – et vous faisaient croire que vous vouliez être19 ». En outre, les récits des trajectoires diasporiques sont rarement limpides, et le travail qui consiste à les mettre au jour est souvent encadré, voire cloisonné, dans des disciplines qui se croisent peu.

Reconsidérer des interactions négligées peut permettre un élargissement, un ajout de valeurs tonales à des teintes qui, avec le temps, ont été estompées ou décolorées. Lorsque l’on aborde l’influence de contributions culturelles plus vastes, en se concentrant sur des récits qui ont été jusqu’ici partiellement reconnus, des liens se révèlent. Ainsi considérée, l’histoire d’A. Fidelin renferme nombre de pistes et de questions à explorer. Je cherche à poursuivre cette démarche, à la déployer et à faire de la place pour davantage d’espace – pour la spécificité, pour la nuance, pour la reconnaissance et pour la visibilité.

À la suite de sa résidence à AWARE: Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, Clare Patrick a reçu la bourse British Art Network 2025-26, soutenue par la Tate et le Paul Mellon Centre, afin de poursuivre ses recherches sur Adrienne Fidelin.

« Self-making ». Hartman, Saidiya V., Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America, New York, Oxford University Press, 1997.

2

Archer-Straw, Petrine, Paradise, Primitivism, and Parody, dans Enwezor, Okwui, Basualdo, Carlos, Meta Bauer, Ute, Ghez, Susanne, Maharaj, Sarat, Nash, Mark et Zaya, Octavio (dir.), Créolite and Creolization. Documenta11_Platform3, Ostfildern-Ruit, Hatje Cantz, 2003, p. 63-76.

3

Cité d’après Poupeye, Veerle, Caribbean Art, Londres, Thames & Hudson, 1998, p. 184.

4

Man Ray, lettre à Adrienne Fidelin (retournée ou non envoyée), 1er septembre 1940. Box 2, Folder 4, Man Ray Archives, Getty Research Institute, Getty Reference Library, Los Angeles.

5

Man Ray, Selfportrait (1963), Londres, Penguin Random House, 2012.

6

Pineau, Gisèle, Ady, soleil noir, Paris, Philippe Rey, 2021.

7

Tancons, Claire, « Women in the Whirlwind: Withholding Guadeloupe’s Archipelagic History », Small Axe, vol. 16, no 3, novembre 2012, p. 152.

8

Grossman, Wendy A., « Entre l’appareil et la toile. Man Ray, Pablo Picasso, et la représentation d’Adrienne Fidelin », traduit de l’anglais par Étienne Gomez, Photographica, no 2, 2021, p. 11-33 [https://doi.org/10.54390/photographica.363].

9

Patterson, Sala Elise, « Yo, Adrienne », New York Times, 25 février 2007 [https://www.nytimes.com/2007/02/25/style/tmagazine/25tmodel.html].

10

Une danse populaire originaire de Martinique et de Guadeloupe, popularisée à Paris par les personnes venues des Caraïbes lors de l’ère du jazz.

11

Lettre originale au sein du fonds d’archives Man Ray, bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Pompidou, Paris.

12

Hartman, Saidiya, « Venus in Two Acts », Small Axe, vol. 12, no 2, no 26, juin 2008, p. 1-14.

13

Kearney, Beth et Thomas, Bonnie, « Uncovering Adrienne Fidelin: Disorderly Subjectivity in Gisèle Pineau’s Ady, soleil noir », Francosphères, vol. 11, no 2, décembre 20221, p. 227-245 [https://www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/doi/epdf/10.3828/franc.2022.17].

14

Le titre de ce film masque l’étendue des prises, car les scènes ont été tournées lors de voyages à travers le sud de la France tout au long des années 1930 et incluent des prises de vue des ateliers parisiens de Man Ray.

15

Glissant, Édouard, Le Discours antillais, Paris, Gallimard, coll. « Essais », 1981.

16

Le 33, rue Blomet était alors un point de ralliement de la diaspora à Paris et un lieu de découverte pour des générations d’artistes avant-gardistes. Voir les textes de John Cowley et d’Ingrid Kummels. Aujourd’hui renommé Bal Blomet, le club a été réhabilité par un investisseur privé. Je n’ai pas obtenu de réponse à ma demande d’accéder à leurs archives dans l’espoir de combler les lacunes persistantes de l’historiographie. Dans le hall d’entrée, j’ai toutefois vu des affiches montrant, parmi les client·es, des artistes blanc·hes (Brassaï, Alexander Calder, Jean Cocteau et P. Picasso), et comme unique star, l’artiste Joséphine Baker. Mes recherches dans les programmes conservés au sein des archives plus fournies et accessibles du Théâtre des Champs-Élysées ne m’ont pas permis de retrouver de documentation physique de la carrière artistique d’A. Fidelin.

17

Archer-Straw, Petrine, Negrophilia, New York, Thames and Hudson, 2000, p. 16. Traduit de l’anglais.

18

« En 1998, un ancien assistant de Man Ray interrogé à son sujet la pensait morte. » Felder, Rachel, « Overlooked No More: Ady Fidelin, Black Model “Hidden in Plain Sight” », New York Times, 29 avril 2022, [https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/29/obituaries/ady-fidelin-overlooked.html]. Traduit de l’anglais.

19

Tancons, Claire, « Women in the Whirlwind: Withholding Guadeloupe’s Archipelagic History », op.cit., p. 155. Traduit de l’anglais.

Clare Patrick est née et a grandi au Cap, en Afrique du Sud. En 2023-2024, elle a été Curatorial Fellow à NXTHVN, à New Haven. Elle a auparavant occupé des postes curatoriaux à la Norval Foundation et à l’Eclectica Contemporary, au Cap, ainsi qu’au Royaume-Uni, à mother’s tankstation et The Lightbox. Clare Patrick a enseigné l’histoire de la photographie au Paris College of Art et contribue au développement des programmes de L’AiR Arts Association. En tant que directrice artistique de SAAG Anthology et de No! Wahala Magazine, elle soutient les solidarités diasporiques et le développement de la pensée autour des pratiques artistiques africaines contemporaines.

Clare Patrick, « Entre ses mains : Adrienne Fidelin » in Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, [En ligne], mis en ligne le 3 octobre 2025, consulté le 28 janvier 2026. URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/magazine/entre-ses-mains-adrienne-fidelin/.