Interviews

Olinda Reshinjabe Silvano and Silvia Ronincaisy Ricopa, © Photo: Alina Ilyasova, all rights reserved

Gala Berger, Olinda Reshinjabe Silvano and Miguel A. López. Curators of the exhibition Madres Plantas y Mujeres Luchadoras. Visiones desde Cantagallo [Mothers Plants and Struggling Women. Visions from Cantagallo] at MAC Lima, 2022, © photo: Juan Pablo Murrugarra

Exhibition view, Madres Plantas y Mujeres Luchadoras. Visiones desde Cantagallo [Mothers Plants and Struggling Women. Visions from Cantagallo], MAC Lima, 2022, © photo: Juan Pablo Murrugarra

Exhibition view, Madres Plantas y Mujeres Luchadoras. Visiones desde Cantagallo [Mothers Plants and Struggling Women. Visions from Cantagallo], MAC Lima, 2022, © photo: Juan Pablo Murrugarra

Exhibition view, Madres Plantas y Mujeres Luchadoras. Visiones desde Cantagallo [Mothers Plants and Struggling Women. Visions from Cantagallo], MAC Lima, 2022, © photo: Juan Pablo Murrugarra

Exhibition view, Madres Plantas y Mujeres Luchadoras. Visiones desde Cantagallo [Mothers Plants and Struggling Women. Visions from Cantagallo], MAC Lima, 2022, © photo: Juan Pablo Murrugarra

Towards the end of the 1990s, the Seminario de Historia Rural Andina (SHRA), founded in 1966 by historian Pablo Macera at the National University of San Marcos in Lima, Peru, initiated an ambitious effort to highlight Amazonian indigenous history. Part of this project has involved organising exhibitions of work by artists from the Shipibo-Konibo community, amongst them Elena Valera Bawan Jisbe (1968–) and Lastenia Canayo García Pecón Quena (1962–). The research, workshops and exhibitions developed with the project led, in 2008, to the inclusion of kené designs on the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage by the Peruvian National Institute of Culture, in an official recognition of the aesthetic, symbolic and spiritual value of these motifs. This dynamic endured into the 2020s: in 2022, the MAC Lima, under the impetus of Gala Berger and Miguel A. López, hosted the exhibition Madres Plantas y Mujeres Luchadoras. Visiones desde Cantagallo [Mothers Plants and Struggling Women. Visions from Cantagallo]. The exhibition was devoted to the contemporary visions of Shipibo-Konibo women artists residing in Cantagallo, a neighbourhood of Lima that is home to one of Peru’s largest urban indigenous communities.1 Canela Laude-Arce met one of the exhibition’s artists and curators, Olinda Reshinjabe Silvano (1969–).

O. Silvano is a Shipibo-Konibo artist, singer, community spokesperson and traditional healer based in the indigenous neighbourhood of Cantagallo, Lima, Peru. In this interview for AWARE, she discusses her artistic practice and the importance of collective work, notably within the groups Madres Artesanas de Cantagallo [Artisan Mothers of Cantagallo] and Soi Noma. As her works are becoming increasingly visible in Peru and in the art market, this exchange also considers the ways in which Shipibo-Konibo art is received in a variety of contexts. Finally, O. Silvano explores the challenges she faces in her position as a community spokesperson and the essential role played by the Cantagallo Shipibo-Konibo community in the struggle to end discrimination and preserve indigenous cultural and artistic traditions.

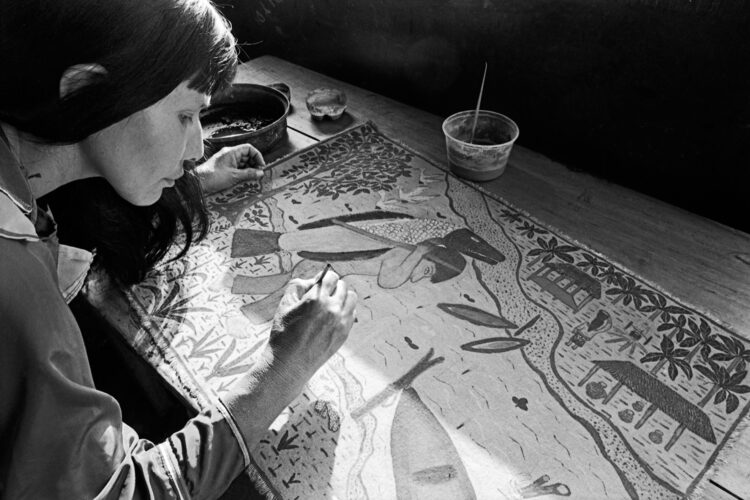

Olinda Reshinjabe Silvano in her studio in Cantagallo, August 2024, © photo: Canela Laude-Acre

Olinda Reshinjabe Silvano in her studio in Cantagallo, August 2024, © photo: Canela Laude-Acre

Olinda Reshinjabe Silvano in her studio in Cantagallo, August 2024, © photo: Canela Laude-Acre

Olinda Reshinjabe Silvano in her studio in Cantagallo, August 2024, © photo: Canela Laude-Acre

Canela Laude-Arce: Dear Olinda, could you describe to us how your artistic practice began?

Olinda Reshinjabe Silvano: It hasn’t been easy. I come from a modest family in the indigenous community of Pauviano, in Bajo Ucayali. Never in my life did I imagine I would one day make it to Lima. When I was a child, my grandmother cared for me using plants like piri piri, which she would apply to my eyes and body so that my whole being could absorb their properties. [Note: O. Silvano was born prematurely and required special care in her early years. In several interviews, she describes how her grandmother placed an ‘invisible crown’ on her head – something she believes still protects and inspires her to this day.2] At the time, I didn’t realise that this process was all part of my preparation for the future. Art changed me – it took me far.

Since childhood, I’ve loved to draw. I lacked the proper materials so I would sweep the ground under a tree and trace shapes in the earth. In my community, we had to grow cotton and wait a year, sometimes more, before we could spin it into thread for weaving. So I drew directly in the soil – even if, by the end of the day, the rain would wash it all away. As I got older, I managed to buy a small piece of embroidered fabric. I would collect the stray threads scattered on the ground and use them to create my first embroidery pieces. When I was eight, a foreign woman bought one of my works. That moment gave me the strength and motivation to keep going. I also learned the art of kené from my family.

As a teenager, I decided to leave for Pucallpa. I wanted to study, dress how I liked and be free. My grandmother had other plans for me: she wanted me to marry an older man. I, on the other hand, wanted to learn, to work, and to carve out my own path, even if it meant doing it alone. At the time, that was a real challenge.

In 1996 I left Pucallpa for Lima, in search of a better life and a future for my children. At first I settled in Comas, but through my cousin I learned that a community was forming in Cantagallo. From the moment I arrived, I felt a deep connection – as if I were returning to my roots, to my identity. I began selling handmade crafts there, even though we faced many hardships: discrimination, mistreatment and precarious living conditions. As an Indigenous woman, I’ve learned to work with honesty and to live through effort and perseverance. We fight. We hold on to hope – even when exhaustion weighs us down, even when our feet burn from walking too far. I used to work from six in the morning until eight at night, just to bring something home to my family. That’s how I grew up – learning to do everything. My father taught me how to fish, to plant, to craft, and most importantly, to work with kindness and to help others.

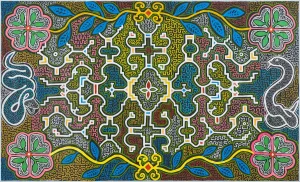

Soi Noma Collective, Maya Kené. Río Ucayali, 2024, Courtesy of Galería del Paseo, Lima

Julia Ortiz and Olinda Reshinjabe Silvano, Historias de la selva y la ciudad [Stories of the Jungle and the City], 2013, oil paint, natural dyes, and traditional Shipibo embroidery on tocuyo cotton canvas, 130 × 153 cm

C. Laude-Arce: The collectives to which you belong – Madres Artesanas de Cantagallo [Artisan Mothers of Cantagallo] and Soi Noma – are based in the Shipibo-Konibo community in Cantagallo. How did this community develop?

O. Silvano: When I arrived in Cantagallo in 2000, it was little more than an empty, barren lot. My house was one of the first to be built, and soon other families began to join us. Little by little, we started selling our crafts and working together, speaking our own language. That’s essential to me – because I’m not mestiza: even though I speak Spanish, there are times when people still don’t fully understand me. That’s how our community developed. And yet, after twenty-five years, we still haven’t been granted land titles. The Peruvian state continues to deny us recognition. We don’t understand why, as Indigenous people, we are still unable to obtain legal acknowledgment of land that is rightfully ours. [Note: O. Silvano’s father died from injuries sustained during a beating in Cantagallo while defending his right to occupy the land. The artist has notably explored this tragedy in her piece Historias de la selva y la ciudad [Stories of the jungle and the city, 2013], created in collaboration with artist Julia Ortiz (1975–), who also lost her father, a victim of terrorism. With the assistance of curator César Ramos Aldana, it was one of the first works by O. Silvano to be presented in an institutional context, at the exhibition Mujeres de la floresta. Arte originario, popular y contemporáneo [Women of the forest. Indigenous, popular and contemporary art] at the Centro Cultural de España in Lima, in 2013.3]

On the night of 4 November 2016, at eleven o’clock, a devastating fire swept through our community. We lost everything – our homes, our belongings… we were left with nothing. But with courage and solidarity, we began to rebuild, little by little. Creating murals became a form of therapy for us. After going through such a traumatic experience, many of us struggled to sleep. These works of art brought us a sense of peace and gave us the strength to continue our fight. Through this struggle, we managed to secure essential infrastructure: a dining hall, an infirmary, access to water and electricity, a water tank and a cultural centre. We continue to work toward our next goal – creating a proper health centre.

Exhibition view, Encuentro de ríos [Confluence of Rivers], Soi Noma collective, Galería del Paseo, Lima, 2024

Exhibition view, Encuentro de ríos [Confluence of Rivers], Soi Noma collective, Galería del Paseo, Lima, 2024

Exhibition view, Encuentro de ríos [Confluence of Rivers], Soi Noma collective, Galería del Paseo, Lima, 2024

ARCOMadrid 2025, Wametisé: ideas para un Amazofuturismo [Wametisé: ideas for an Amazofuturism], All rights reserved

C. Laude-Arce: You mentioned the creation of collective mural works. How would you describe the importance of community work in your artistic practice? And have you noticed a shift in how Shipibo-Konibo art is perceived – both in Peru and internationally?

O. Silvano: In 2014 we founded the Shipibo-Konibo muralist collective Soi Noma, which I lead. It originally brought together only women from the Cantagallo community, including Wilma Maynas Inuma (1964–) and Silvia Ronincaisy Ricopa (1965–). Our first mural was created on 28 July, Peru’s national holiday. Over time – and especially during the COVID-19 pandemic – our group grew. Today, the group consists of twelve women and four men muralists. Little by little, Peruvians have started to appreciate our artistic work. We’ve painted in places such as the San Isidro Cultural Center and, in 2015, at LUM in Lima. [Note: In 2024, the Soi Noma collective presented its first solo exhibition at Galería del Paseo in Lima. Curated by Giuliana Vidarte, Encuentro de ríos [Confluence of Rivers] featured works by O. Silvano, S. Ricopa and artists Salome Buenapico Silvano (1987–), Dora Inuma (1952–), Delia Pizarro (1979–), Cordelia Sánchez Pesin Kate (1965–), Sadith Silvano (1988–), Jessica Silvano (1982–) and Nelda Silvano (1970–).4]

However, it is abroad that we receive much greater recognition. For example, our textile design creations have been very well received in the United States – in California, New York and Santa Fe – because they meet a growing demand for sustainably made clothing, here using natural dyes extracted from plants such as mahogany, mango and guava. [Note: Outside Peru, O. Silvano has participated – either individually or collectively – in exhibitions held at the Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver (2018) for Arts of Resistance: Politics and the Past in Latin America, at the Centre de Cultura Contemporània of Barcelona (CCCB) in 2024 for Amazonias. El futuro ancestral [Amazonias. The ancestral future] and as part of the thematic programme Wametisé: ideas para un Amazofuturismo [Wametisé: ideas for an Amazofuturism] at ARCOMadrid in 2025.]

Muralism has become a space of resilience and therapy for us. Painting together allows us to express our emotions, share, laugh, imagine and sing. It has brought us comfort in difficult times. Today, in addition to our collective work, I am regularly invited to paint abroad. When I travel, I can only take two or three colleagues with me. We’ve already created murals in Washington, at the Inter-American Development Bank, and soon we’ll be heading to Argentina. Kené embodies unity, and I hope that through it, the Shipibo-Konibo identity will not disappear.

Berger, Gala, “Mother Plants and Struggling Women: Visions From Cantagallo: An Interview with Olinda Silvano”, Independent Curators International (2022). Online: https://curatorsintl.org/records/23598-intensives-in-action-gala-berger

2

Lance, Samantha, “Olinda Reshinjabe Silvano: Finding Solidarity with Indigenous Communities through Ancient Shipibo-Konibo Practices”, The Power Plant (2023). Online: https://www.thepowerplant.org/learn-and-explore/features/olinda-reshinjabe-silvano-finding-solidarity-with-indigenous-communities-through-ancient-shipibo-konibo-practices

3

Yllia, María Eugenia, “Julia Ortiz and Olinda Silvano (Reshinjabe) Rewrite Their History”, INSITE Journal (2022). Online: https://insiteart.org/common-thread/in-focus/julia-ortiz-and-olinda-silvano-reshinjabe-rewrite-their-history

4

Vidarte Basurco, Giuliana. “Pintar un nuevo kené en territorios de migración y crisis medioambiental: Olinda Silvano Reshinjabe y el colectivo Soi Noma”. América sin Nombre, 32 (2025): pp. 179–197, https://doi.org/10.14198/AMESN. 27622

Olinda Reshinjabe Silvano (1969–) is a Shipibo-Konibo artist, singer, community spokesperson and traditional healer. Originally from the region of Bajo Ucayali, she moved to Lima in the 2000s and participated in the founding of the indigenous neighbourhood of Cantagallo. She is the president of the AYLLU women’s association, and works to protect traditional knowledge and the rights of Andean and Amazonian indigenous communities. Her works have been displayed at the CCCB in Barcelona, the ARCO art fair in Madrid, the Inter American Development Bank and the museum of the National University of San Marcos in Lima.

Canela Laude-Arce is a French-Peruvian political scientist, holding degrees from King’s College London, SOAS University of London and the Institut des hautes études de l’Amérique latine. Her work specialises in the intersection of cultural and political issues, particularly in Latin America. In her recent research, she has analysed the art of the Peruvian Amazon and its exhibition in museums in France and Peru. She is a regular contributor to Lupita magazine, where she publishes portraits of Latin American artists based in Paris.

Canela Laude-Arce, "An invisible crown: the voice of Olinda Reshinjabe Silvano." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/une-couronne-invisible-la-voix-dolinda-reshinjabe-silvano/. Accessed 12 June 2025