Research

Painting restoration, an aspect of collection history that remains regrettably little known, was long practised by men and women whose main line of work was selling or producing paintings. Their shops and homes often sat side by side, with employees and family members coming and going throughout the day. This arrangement undoubtedly made it easy for women to carry out professional duties and keep an eye on their households at the same time. In the workshop, parents, children, apprentices and servants would all labour alongside each other in an approach allowing women and girls to play an active role. After learning the trade, they might serve behind the counter or at the workbench, but today their identities and specific duties are often impossible to trace.

A recently published dictionary of Parisian restorers covering the period from 1750 to 1950 lists around one thousand professionals, amongst whom only around sixty women are mentioned.1 A few names were gleaned from professional directories2 and museum archives,3 the women always easily identifiable from annotations detailing their marital status or kinship bonds: “widow of”, “wife of” or “daughter of”.

At the helm of a business

At that time, the work of painting restoration encompassed two very distinct specialisms, one concerned with the support and the other with the paint layer. Long regarded as the craft rather than the art of the practice, support restoration earned prestige with the first executions of canvas lining and, above all, due to the skill of those who pioneered the transfer technique.4 In this field, various prominent women left their mark on history, particularly after becoming widows. The special legal status granted to widows in the Ancien Régime enabled them to officially take over the management of their late husbands’ workshops.5 Such was the case for a widow named Lange (dates unknown), who in 1688 was remunerated for lining Titian’s renowned Pardo Venus (also known as Jupiter and Antiope).6 This is one of the earliest documented examples of the technique in which a new canvas is adhered to the back of an original to reinforce it.

A few decades later, another widow, Marie-Jacobe Godefroid (c. 1700–1775), used this same technique. She became as famous as her contemporary and rival Robert Picault (1705–1781), who brought the transfer technique to France, by offering this service at a more competitive price and, moreover, by revealing the method involved and thus foiling the strategies of other competitors.

Marie-Jacobe Van Merle was born into a family of artists and artisans. Registered at the Académie de Saint-Luc as a “master’s daughter”, she married Ferdinand-Joseph Godefroid (1709–1741), a merchant and painting restorer, in 1726; together they had seven children. Her sudden widowhood prompted her to take over the management of their business, located in Paris at the Cloître Saint-Germain. As her new status permitted, she also succeeded her husband in the coveted position he held with the king “for the maintenance and restoration of His Majesty’s paintings” and consequently received a pension, which from 1743 she shared with her business partner François Louis Colins (1699–1760). In this way, she built an exceptional career, her determination and professional skills enabling her to thrive in the trade for more than thirty years. Her work was not limited to the royal and princely collections but also included the large-scale decorations of the Château de Versailles and the Rubens paintings in the Palais du Luxembourg’s Galerie Médicis. While she focused primarily on canvas and wooden supports, she also carried out cleaning, inpainting and varnishing procedures, although she delegated major retouching assignments to her colleagues.7

Working in the capacity of a pupil, wife or daughter of a male restorer

It is challenging to make general statements about the tasks entrusted specifically to women in art restoration workshops, and even harder to identify distinct careers, apart from a few exceptions. Even when a single person performed certain restorations, the distinction between a painting’s support and paint layer led, as previously noted, to a division of labour within the profession. The retouching of highly valued works was entrusted to renowned painters; in this area, women restorers seem often to have been limited to more minor tasks. For instance, when Mademoiselle Veret (dates unknown) assisted celebrated restorer Edme Mathias Barthélemy Röser (1737–1804) at the Louvre, her duties included “blocking in the fillers”, i.e. laying down the initial tones, and “stippling” spots and cracks;8 this work was obviously less distinguished than the retouching performed by E. M. B. Röser himself. Nonetheless, she lived more than twenty years beyond her master, and her listing in restorers’ section of the commercial almanacs until 1823 confirms that she continued to work, although no additional records of her practice have been found.

Other women practised art restoration as well, frequently by virtue of their marital ties. Thus, Madame de Monpetit (dates unknown), wife of painter Vincent de Montpetit (1713–1800), and Madame Boutelou (dates unknown), who was married to engraver Louis Alexandre Boutelou (1761–179?), were likewise active in restoration work. In 1794 the Louvre’s first restorer recruitment competition even attracted an application from a married couple: a certain Duval, “Dutch painter and restorer” and his wife. Such historical records demonstrate women’s practical involvement in painting restoration.9

Lastly, training was naturally facilitated by family ties: Marie Émilie Maillot (1798–1836), a daughter, wife and mother of restorers, was introduced to the trade by her father, Pierre Carlier (1743–1818), who worked for the royal museums. She was mentioned alongside him as early as 1817, although her role was not clearly specified, and she continued her career after marrying restorer Nicolas Sébastien Maillot (1781–1857), who had also trained in her family’s workshop and later took over its management himself. M. E. Maillot worked tirelessly at her husband’s side and contributed to all his significant projects. Surviving memoirs suggest that the painting retouches were mainly done by her husband, who was also a professional painter, while she handled cleaning and varnishing. This division of labour may account for the disparity in their wages: M. E. Maillot earned five francs per work session, whereas her husband received six to nine francs. Although the quality of their respective duties is difficult to judge today, what is certain is that although she began at a very young age, her career did not enable her to assume leadership of the family workshop.

Women as both painters and restorers

In the final decades of the Ancien Régime, a phenomenon emerged that undeniably facilitated women’s access to professional artistic training;10 their inclusion as exhibitors at the Paris Salon, albeit very limited, is evidence of this. For many of these women painters, art restoration represented a supplementary source of income. Antoinette Béfort (1788–1868),11 who showed works at the 1810 and 1812 Paris Salons, was noted in 1824 for having “restored and varnished a painting by Perugino”.12 Moreover, artists exhibiting at the Paris Salon could undertake institutional copy commissions, which became increasingly common in the first half of the 19th century. Official portraits and religious paintings were reproduced on commission, and women artists were often called upon for this work. Copying was considered a respectable pursuit and also offered opportunities to practice and learn from the great masters. Indeed, mastery of copying was required in restoration, as demonstrated by the proceedings of the Louvre’s second recruitment competition in 1848, which aimed to register restorers on a list of qualified practitioners. Of the 126 applicants, there were just five women, and they were registered only for the examinations focused on “repairing” the paint layers of history and genre paintings. Madame Giraudeau (dates unknown) and Madame Colin (dates unknown) are documented in this regard, while the others are also known to us as copyists and Paris Salon exhibitors: Catherine Esther Paris-Persenet (1804–1887),13 Estelle Dupré (dates unknown)14 and Valentine Mihl or Milh (dates unknown).15

Defining women’s role in the workshops

Aside from the art classes slowly becoming accessible to women, family workshops practising professional endogamy remained the primary vector for women’s training in restoration until the mid-20th century. When women succeeded their husbands, was it merely to run the businesses, or did they also receive training to perform restoration work themselves? The archives are often silent on this point. The fact remains that women were allowed to continue a workshop’s operations, whether they were a restorer’s widow – such as Marie Madeleine Belot (c. 1847–1814),16 Angélique Honorine Haro (1801–1869)17 and Thérèse Vallé (1808–1893)18 – or daughter, like Mademoiselle Heuzey (dates unknown)19 and Louise Mercier (1862–after 1924).20

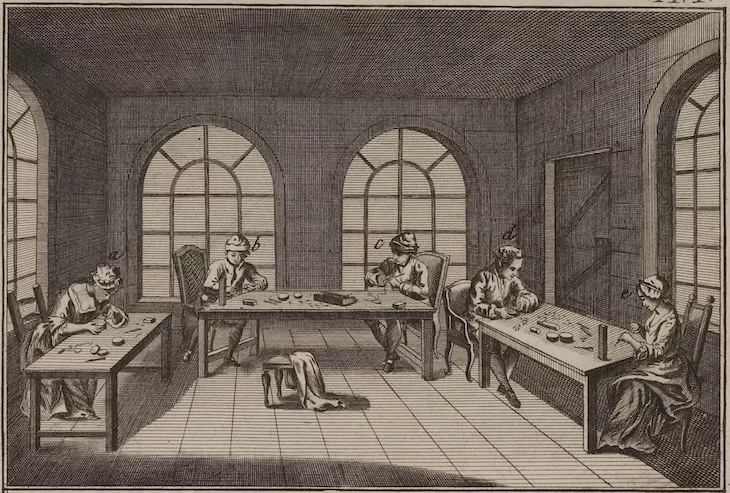

Documentation of women’s practice as restorers at workshops is as sparse as that for other employees or family participants. A rare photograph of the workshop of Marc-Terence Müller de Schongor (1865–1938) founded in around 1880 nevertheless offers insight into their role, showing two women equipped, like the men, with hand rests and palettes, essential implements of their profession.21

Although women restorers were still very much in the minority over the first half of the 20th century, nonetheless their involvement in projects for the City of Paris is attested by a few names, such as that of Élisabeth Faure (1906–1964),22 and even for the Louvre, with Mademoiselle Evrard (dates unknown), who worked on the collections in the aftermath of the First World War. Yet no woman was hired in the Louvre’s recruitment competition of 1935: Marguerite Henckel (dates unknown), the only female candidate, clearly did not demonstrate sufficient skills, although “her great docility suggests that, if necessary, she could serve as an assistant,” as workshop head Jean-Gabriel Goulinat (1883–1972) noted in the examination’s deliberation report.23 Women were thus consistently active in the field of restoration, yet remained largely invisible until the latter half of the 20th century. Only a few documented cases attest to their work: more than their male counterparts, female restorers had to operate in the deepest shadows. They did however gain greater prominence as the profession matured over the two centuries and ultimately adopted a formal ethical code in the 21st century.

Nathalie Volle, Béatrice Lauwick and Isabelle Cabillic (eds), Dictionnaire historique des restaurateurs. Tableaux et œuvres sur papier. Paris, 1750–1950 (Paris: Mare & Martin et Louvre Éditions, 2020).

2

Commercial almanacs.

3

Collection of the Archives des Musées Nationaux, held at the Archives Nationales.

4

A procedure in which the paint layer is removed from its original support and attached to a new backing.

5

Freed from a husband’s authority, widows acquired full legal rights which enabled them to manage their own property and enter into contracts on their own behalf.

6

Nathalie Volle, “Titien et ses restaurateurs: Jupiter et Antiope, un tableau palimpseste”, Technè, no. 27–28, 2008, pp. 21–28.

7

Colins until his death in 1760, then Guillemard and her own son, Joseph Ferdinand Godefroy (1729–1788).

8

Documentation of her work appears in the Musée du Louvre’s accounts for 1801 and 1802.

9

Archives Nationales 20144790/117.

10

See Séverine Sofio, Artistes femmes. La parenthèse enchantée (XVIIIe-XIXe siècle) (Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2023), pp. 307–309.

11

She was a student of Gioacchino Serangeli (1768–1852), who himself had studied under Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825).

12

Archives Nationales 20150539/17.

13

A genre and portrait painter, pastellist and copyist, she studied under Auguste Couder (1789–1873) and exhibited at the Paris Salon from 1831 to 1868.

14

She exhibited at the 1850 Paris Salon and produced copies purchased by the State between 1848 and 1875.

15

She showed works at the Musée de Nantes in 1845 and 1848, then at the 1848 Paris Salon, and painted many copies commissioned by the State.

16

Marie Madeleine Belot (née Place) took over from her husband, Michel Belot (1730–1792).

17

In 1844 Angélique Honorine Haro (née Osmont) assumed control of Maison Haro, established in around 1824 by Jacques-François Haro (1797–1844).

18

In 1845 Thésèse Esther Vallé (née Harpé) took over Maison Vallé, founded in around 1825 by Pierre Auguste Vallé (1801–1845).

19

Restorer Ferdinand Heuzey’s daughter continued his business at the same address starting in 1882.

20

Louise Mercier, daughter of restorer Charles Mercier (1832–1909), exhibited at the Paris Salon from 1879 to 1907 and took over his workshop in 1910 before partnering with Albert Jehn in 1912.

21

Dalila Müller (1867–1935), second from right, stands next to her brother Marc-Terence Müller.

22

A pupil of Lucien Simon (1861–1945), she exhibited at the Paris Salon from 1933 and worked on numerous projects in Paris, including the church of Saint-Merry in June 1941.

23

Archives Nationales 20150497/33.

Béatrice Lauwick, "Women painting restorers in Paris before 1950." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/les-restauratrices-de-peinture-a-paris-avant-1950/. Accessed 25 January 2026