Mierle Laderman Ukeles

Kari Conte (ed.), Mierle Laderman Ukeles: Seven Work Ballets, Berlin, Sternberg, 2015

→Miwon Kwon, “In Appreciation of Invisible Work: Mierle Laderman Ukeles and the Maintenance of the ‘White Cube’.”, Documents, n°10, Automne 1997, p. 15-18

→Sue Spaid, Ecoventions: Current Art to Transform Ecologies, OH: Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinatti, 2002

Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Maintenance Art, Queens Museum of Art, New York City, September 18, 2016 – February 18, 2017

→Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Matrix 137, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford (USA), September 20 – November 15, 1998

→Fragile Ecologies, Queens Museum of Art, 1992

→Touch Sanitation Show, Ronald Feldman Fine Arts et DSNY West Fifty-Ninth Street Marine Transfer Station, New York, 1984

US eco-artist.

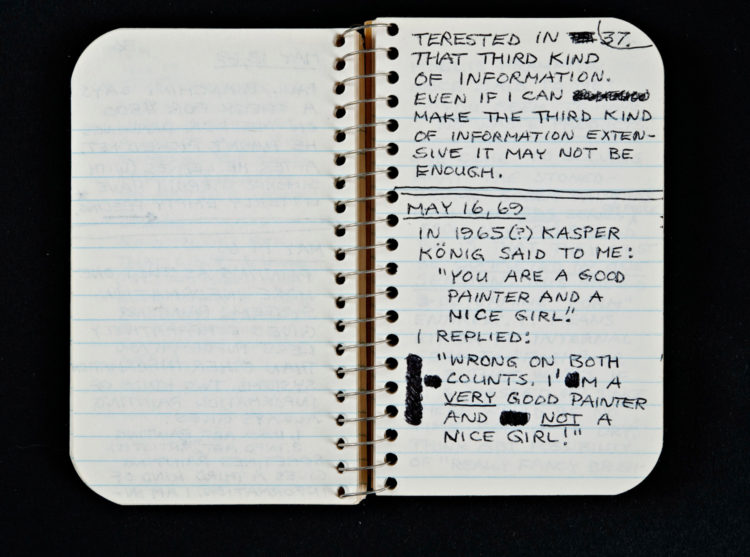

Ecofeminist conceptual artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles first made a name for herself more than fifty years ago with her Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969!, a critical extension of the readymade concept that allowed her to reclaim her own artistic agency through care activities traditionally practiced by stay-at-home mothers. M. L. Ukeles was deeply hurt when, after her pregnancy became obvious, she was pressured to drop out of an arts degree programme at the Pratt Institute. At the time, she saw this rejection as the end of any chance for a career in the arts.

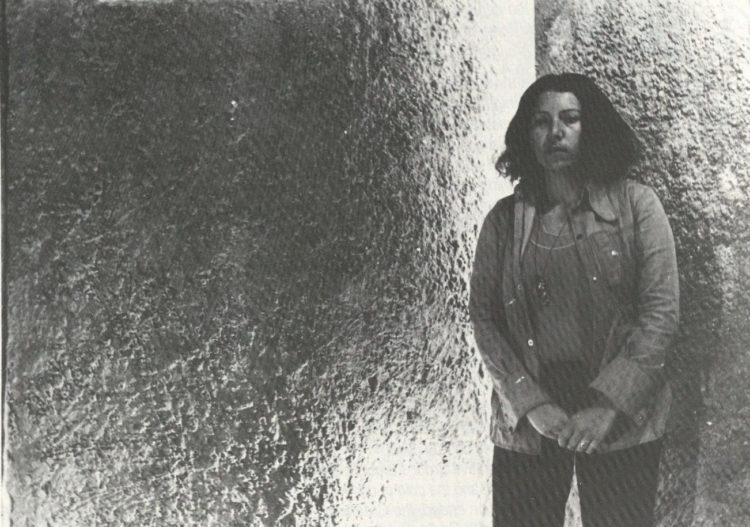

From the very beginning, with her manifesto, M. L. Ukeles connected feminism, ecology, care and subordination in a project aimed at enabling her to transcend traditional gender roles and instituted a forward-looking ethic to living and working. Making and documenting performance art were the first steps she took in implementing what has been called “household art”. Staged initially at her home (with the involvement of her husband, whom she had married in 1966, and their children), then in museum settings starting in 1973 (for example mopping floors and cleaning furniture at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut), her performance pieces gave striking visual form to this bold, new strategy aimed at disrupting the roles imposed on women.

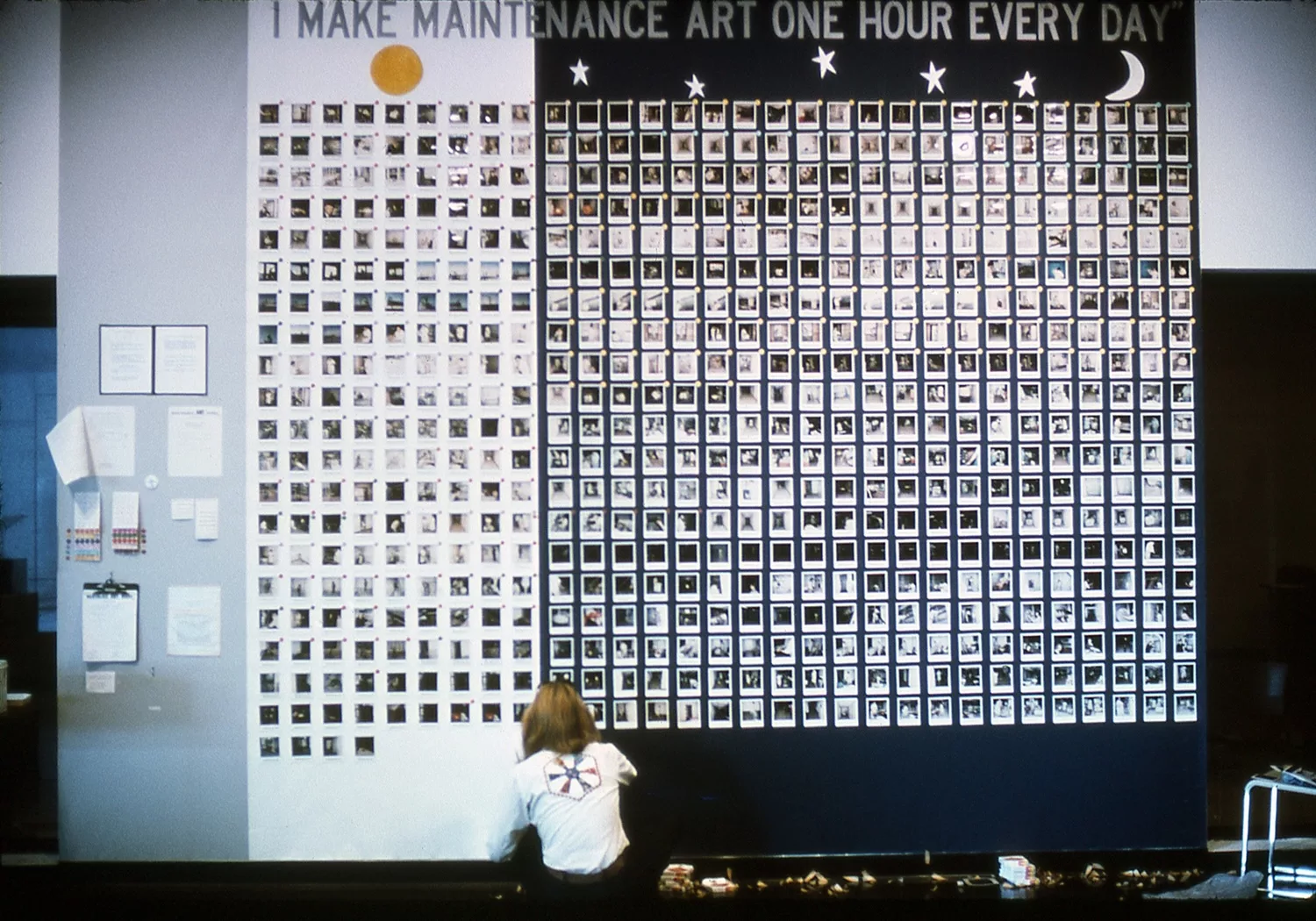

In 1976, two years after earning her master’s in interrelated arts, M. L. Ukeles expanded the duration and scope of her visual analyses. For I Make Maintenance Art One Hour Every Day (1976), she spent a month in New York interacting with the 300 maintenance workers of an office building in a business district where a branch of the Whitney Museum was also located. In this undertaking, she showed how the American economic system relied on maintenance workers who, while vital to business operations, were largely overlooked and unseen because they worked at night.

The following year, she approached the New York City Department of Sanitation with an offer to serve as an unpaid artist-in-residence. Having thus anchored herself in the institutional sphere, she embarked upon Touch Sanitation(1979–1980), a performance piece over a year in the making that culminated in a multimedia installation. For this project, she met with each of the Department of Sanitation’s 8,500 employees to tell them “Thank you for keeping New York City alive” and to take an official photograph. She accompanied these workers on all their rounds and gathered their personal stories as part of her stand against their degrading working conditions; she even went so far as to challenge city officials on this point.

Seeing the city as a living organism and an environment, M. L. Ukeles was one of the first to understand the emergence of social ecology and to separate the idea of ecology from nature. In line with this commitment, in 1989 she entered and won the Percent for Art commission’s competition for a contribution to the redevelopment of the Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island opposite Manhattan. At the time, it was the world’s largest dump and the massive waste accumulation had generated severe pollution, even disrupting air traffic. Its gradual transformation into a recreation park began in 2008 and is slated for completion in 2035; currently, the site encompasses an area equivalent to two and a half Central Parks. Over the past four decades, she has worked to commemorate the landfill, which she views as a collective work co-created with all New Yorkers.

Although she has been represented throughout her career by New York gallery Ronald Feldman Fine Arts and has received numerous awards and grants, the first major retrospective devoted to her art did not take place until 2017. In 2023 ARTnews ranked Touch Sanitation third in its list of New York’s 100 most iconic works of art, a belated recognition that nevertheless delighted M. L. Ukeles, who divides her time between New York and Tel Aviv.

A biography produced as part of the programme “Common Ground”

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2026