Research

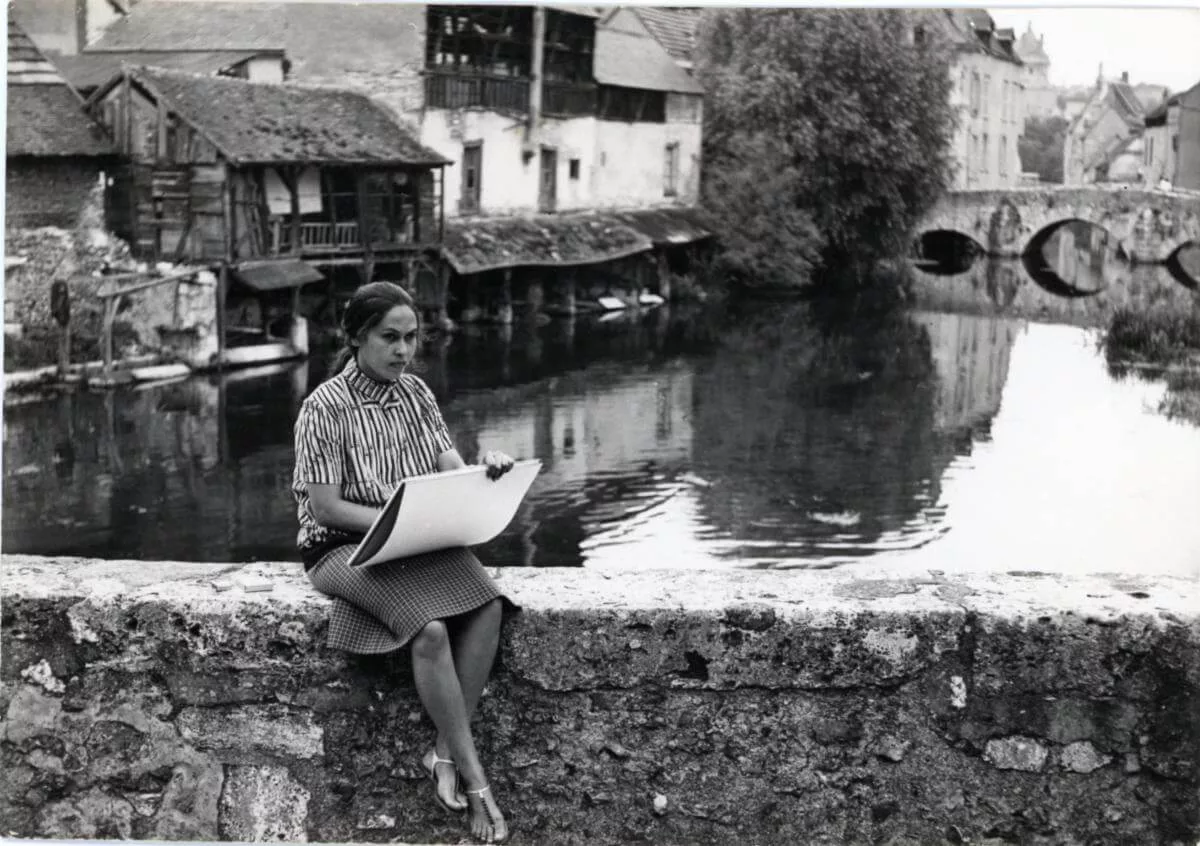

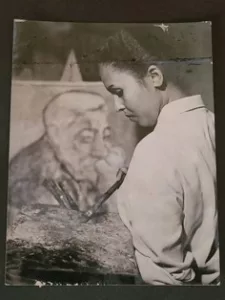

Luce Turnier sketching in Rue de la Grenouillère, Chartres, France, Summer 1960, Collection Centre d’Haïti, All rights reserved

From June to August 2024, I completed a research residency at the AWARE Documentation Centre as part of the Marie-Solanges Apollon programme, conducting research on Luce Turnier (1924–1994), a Haitian-born modernist painter and collagist. Her first connection to France came in 1946, when her oil painting Sarcleur (n.d.) was included in an exhibition of Haitian art at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris, sponsored by UNESCO. After completing a residency in New York, L. Turnier was encouraged to continue her artistic journey in Paris. As her daughter, Jézabel Turnier-Traube, recalls in a podcast produced by the Centre Pompidou for the Paris noir (2025) exhibition, “she was advised to come to France because, at the time, France was the country of painters.”1 Heeding that advice, L. Turnier thus left for Paris, where she lived from October 1951 to 1955, supported by a modest grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, the Institut Français d’Haïti and the generosity of friends and family. From 1951 to 1953, she studied at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, where she was exposed to life drawing workshops, abstract expressionism and other modernist aesthetics.2 She returned to France in 1960, fleeing the Duvalier dictatorship in Haiti. With few financial resources, she initially settled with her family in Lucé, a suburb of Chartres. In 1962, she moved to Paris, then in 1965 to Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, a south-eastern suburb of the city. She later relocated to Champigny-sur-Marne, where she remained until her return to Haiti in 1977.

What we know of L. Turnier’s time in France comes primarily from the memories and recollections of her family and friends. Hers is a story that must be told through the voices of others – a second voice – due to the absence of conventional documentation of her presence in a country that, for many people of African descent, represented a refuge from racism in the United States and an opportunity to pursue academic and economic advancement for citizens of formerly colonised nations.

My desire to research L. Turnier’s creative life stemmed from an attempt to answer two fundamental questions: how do we write a person into history? And how do we come to know their lives when little archival material exists to establish their presence? These questions first arose years ago, during the early stages of my dissertation research. While studying traditional and modern Haitian art, I discovered a trove of materials on the founding of the Centre d’Art d’Haïti and the self-taught artists – mostly men – who worked and studied there. However, there was a notable absence of documentation about the women who taught, took classes and produced work at the Centre, such as Marie-José Nadal-Gardère (1931–2020), Rose-Marie Desruisseau (1933–1988) and Andrée Malebranche (1916–2013). This research project is therefore motivated by a desire to contribute to Black Atlantic art history by inserting into the narrative a Haitian woman artist whose presence has been largely elided. It also engages with Black feminist art history and the practice of archival excavation, focusing on the life and creative output of an understudied woman artist. In doing so, it seeks to address both art historical and aesthetic omissions, contributing to the growing scholarship on women artists of the Black Atlantic. This work aligns with the broader mission of AWARE.

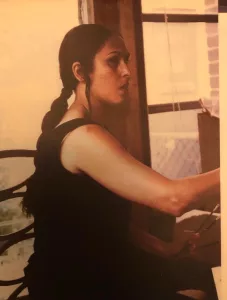

Portrait photograph of Luce Turnier painting, Archival material documented by Jerry Philogène during her 2024 research residency at the AWARE Documentation Centre, as part of the Marie-Solanges Apollon Program

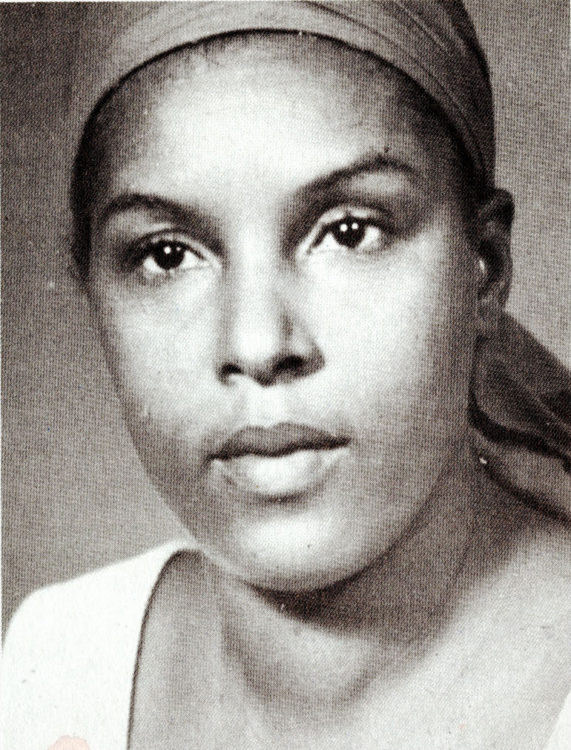

Portrait photograph of Luce Turnier, Archival material documented by Jerry Philogène during her 2024 research residency at the AWARE Documentation Centre, as part of the Marie-Solanges Apollon Program

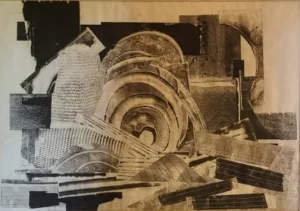

Work by Luce Turnier, Documented by Jerry Philogène during her 2024 research residency at the AWARE Documentation Centre, as part of the Marie-Solanges Apollon Program

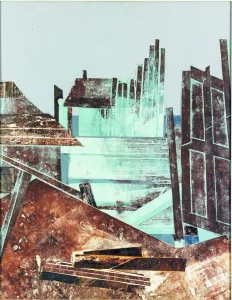

Work by Luce Turnier, 1970, Documented by Jerry Philogène during her 2024 research residency at the AWARE Documentation Centre, as part of the Marie-Solanges Apollon Program

Most of my residency was spent in Paris, where I conducted numerous interviews with her daughters, Jézabel and Léonora, as well as with friends who owned several of her paintings and collages – either gifted to or purchased by them. While in Paris, I also had access to many of her personal papers and diaries, along with sketchbooks preserved by her daughters. I spent a few additional days in Tuscany and Strasbourg, interviewing friends and viewing paintings and drawings by Turnier in their possession. L. Turnier’s story is one of a creative life that resists conventional archives – what is written, what is known, what is expected. It does not follow a narrative of tragedy, rather one marked by omission and elision. Instead, it reveals a prescient and compelling creativity shaped by an individual who refused to let gender or race constrain her artistic ability or ambition. Through these personal memories, handwritten letters on delicate paper, postcards, and black-and-white and colour photographs pieced together, a portrait emerges: a life brimming with imagination, creative energy and joy, yet shadowed by financial and personal challenges. In interviews with her daughters and close friends, we come to know a deeply private and proud individual, devoted to her art, constantly drawing and painting, seeking ways to develop her artistic practice.

Luce Turnier, Nude Woman in Chair, 1977, oil painting on masonite, 32 x 48 in. [81.3 x 121.9 cm], Courtesy of Gardy St. Fleur Collection & Saint Fleur inc.

Luce Turnier, Untitled, 1986, oil on canvas, 109 x 99 cm, Courtesy of Gardy St. Fleur Collection & Saint Fleur inc.

L. Turnier’s subjects ranged from still lifes to landscapes to portraits, all rendered in subtle, muted tones that conveyed a quiet intimacy and affection for her self-possessed sitters. In those sensuous lines and softened colours, she expressed her deep love for painting the Black figure. As a gesture of support, friends often commissioned her to create portraits of themselves or their family members. However, many of her figure paintings were produced after her return to Haiti in 1977. In an interview conducted in English by Donato “Danny” Pietrodangelo in the 1980s in Port-au-Prince, she noted:

“- My favorite period is between 1965 and 1972.

– And that’s when you were in Paris.

– Because that was more abstract. That’s a special period. I like it. […] That’s the time in my life that I had the most concentration. In my whole life.

– At that time, you – from what I’ve read – were experimenting a little more too.

– […] That’s when I started collage for the first time. […] Now I am doing people because I enjoy it very much. […] In Haiti especially. It is not because I am… I don’t know… nationalist, but I think people are very graceful. I am very interested in the figure more than anywhere else. I think the landscapes are more beautiful in France. I like and enjoy more to do landscapes in France, but I enjoy more to do people here.”3

Luce Turnier, Untitled, 1969, collage, 8 × 9 in. [20.32 × 22.9 cm], Collection Fondation Marie et Georges S. Nader

Luce Turnier, Cabane de chantier, c. 1970, Collage, oil on paper, 92 × 74 cm, Collection of Jézabel Turnier-Traube, Courtesy of the Centre Pompidou

During an interview with her daughter Jézabel in August 2024, she reaffirmed that it was in France, during a period of artistic exploration, that L. Turnier began experimenting with collage – an approach that would eventually become a fundamental part of her oeuvre. She began collecting scraps of black and white paper discarded from the mimeograph machine at her workplace, becoming fascinated by the shapes and textures these loose fragments offered. Jézabel recalled how her mother would scatter the cut-up papers across the living room floor, walking slowly around them until a composition revealed itself. She recounted:

“She was working in a law firm as a secretary. [Note: In the podcast produced by the Centre Pompidou for the Paris Noir exhibition, Jézabel Turnier-Traube mentions that this occurred while her mother was working as a secretary at the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS).] She was very bad, [laughs] but the bosses liked her. At that time, there were no photocopiers – just mimeograph machines where you had to load the ink by hand. There was always lots of leftover paper, and she would take it home. She liked the effect of the ink on the paper, the texture of it. A year later, the machine was old and they wanted to throw it out, but they let her take it home. So she had it in the living room, along with her inks. She’d arrange everything on a board, trying different layouts until she figured out the composition she wanted.”

With subtlety and intention, L. Turnier emerged as a pivotal figure engaged in the visual experimentation and aesthetic complexities of Black modernism; her work compels us to rethink African diasporic art historiography by acknowledging Haiti’s cultural, aesthetic and ideological contributions. L. Turnier’s expressive portraits of both men and women sitters elevate the Black figure as a subject of beauty, grace and dignity, emphasising its formal and conceptual significance. Through soft brushstrokes and subdued backgrounds, her canvases radiate a quiet serenity, allowing the presence of her subjects to resonate with emotional and visual depth. A close examination of the formal dynamics of her compositions – particularly her portraits – and the nuanced portrayal of figuration and the representation of women invites us to consider the power and potential of her practice as a conceptual provocateur within the tradition of portraiture.

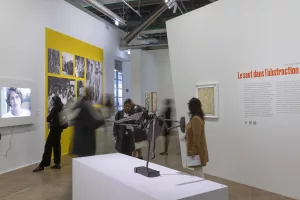

View of the Paris Noir exhibition at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, On screen: video of Luce Turnier interviewed by Donato “Danny” Pietrodangelo © Hervé Véronèse, Courtesy of the Centre Pompidou

Presentation dedicated to Luce Turnier within the Paris Noir exhibition (2025) at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, © Photo: Louise Thurin

Perhaps most importantly, a focused analysis of L. Turnier’s life and oeuvre challenges the male-dominated narrative that has long shaped the origin story of modern Haitian art. Her work reveals the complex intersections of social class, racialisation, gender and representation – reframing how we understand modern Haitian and diasporic art histories.

“From 1945 to 1990, L. Turnier had a continuous if underrecognized exhibition record in France, other European countries, the United States, and Haiti. As we know, the dominant history of Western modernism omits or sidelines artists who have made the political and personal choice to stay on the islands. But in L. Turnier’s case, it is not only her geographic location that has rendered her oeuvre marginalized but also her working outside of what canonically has been recognized as “Haitian art.”’ 4

L. Turnier’s story – like those of many women artists, particularly those of African descent – is marked by neglect, obfuscation and inadequate support. Some details of her life seem to have already been lost, such as documentation of her April 1952 exhibition at the Cité Universitaire’s International House in Paris, where she is known to have exhibited alongside Haitian painters Roland Dorcély (1930–2017), Luckner Lazard (1928–1998) and Max Pinchinat (1925–1985).5 Yet her work will no longer remain in separate and marginalised spaces. L. Turnier now stands alongside artists who are being recovered, reclaimed and reinserted into the annals of Black Atlantic art history. Ultimately, my research project is in dialogue with the broader processes of recovery, cultural memory and the production of history – posing critical questions about who gets remembered, how narratives are shaped and what becomes part of the archive.6

Podcast, Visites d’expos: Paris noir, Centre Georges Pompidou, 2025. Transcription: https://www.centrepompidou.fr/fileadmin/user_upload/Agenda/PDF/transcriptions-podcast/20250319_Paris_noir_-_transcription_du_podcast.pdf Free translation from the French: “On lui a conseillé de venir en France parce qu’à l’époque, la France, c’était le pays des peintres.”

2

Listed in the 1951 Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report, p.428: “HAITI. Miss Luce Turnier, Port-au-Prince; $300 for artists’ materials essential for her studies in painting in France as a fellow of the French government”. https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/Annual-Report-1951.pdf.

3

Interview by Donato “Danny” Pietrodangelo, 1983. Timestamps: 01:33–; 10:30–11:23. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2-oQkQ-u5Rk

4

Philogene, Jerry. “Beyond and against the Archives: Luce Turnier, a Feminist Haitian Modernist.” Small Axe, ‘What and When was Caribbean Modernism? | A 2024 Small Axe Project, 2025.

5

In her unpublished and meticulously researched essay on Roland Dorcély, Judith Kumin notes, “Dorcély, Lazard, Pinchinat and Luce Turnier all had a group exhibition at the Cité Universitaire’s International House in April 1952.” However, despite our combined efforts, neither Kumin nor I have been able to locate further documentation of this exhibition.

6

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston, Beacon Press, 1995.

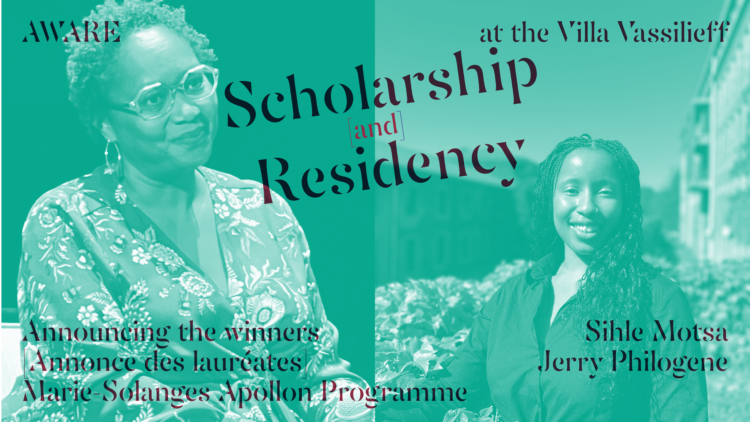

Jerry Philogene is Associate Professor and Director of the Black Studies Program at Middlebury College. She was previously Associate Professor in American Studies Department at Dickinson College, where she specialised in interdisciplinary American cultural history, art history and visual arts of the Caribbean and the African diaspora with an emphasis on the Francophone Caribbean. Dr. Philogene is an independent curator. In 2023 she co-organised with Katherine Smith Myrlande Constant: The Work of Radiance, an exhibition on the contemporary textile works of Haitian artist Myrlande Constant (1968–), at the Fowler Museum, UCLA. Jerry Philogene is the recipient of a 2020 Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant for her book manuscript The Socially Dead and Improbable Citizen: Visualizing Haitian Humanity and Visual Aesthetics. In 2024, she was the first resident of AWARE’s Marie-Solanges Apollon programme, which seeks to highlight women artists of the Black Atlantic.

Jerry Philogene, "Searching for Luce Turnier: The France Years (1951–1955 & 1960–1977)." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/a-la-recherche-de-luce-turnier-les-annees-francaises-1951-1955-et-1960-1977/. Accessed 7 March 2026