Research

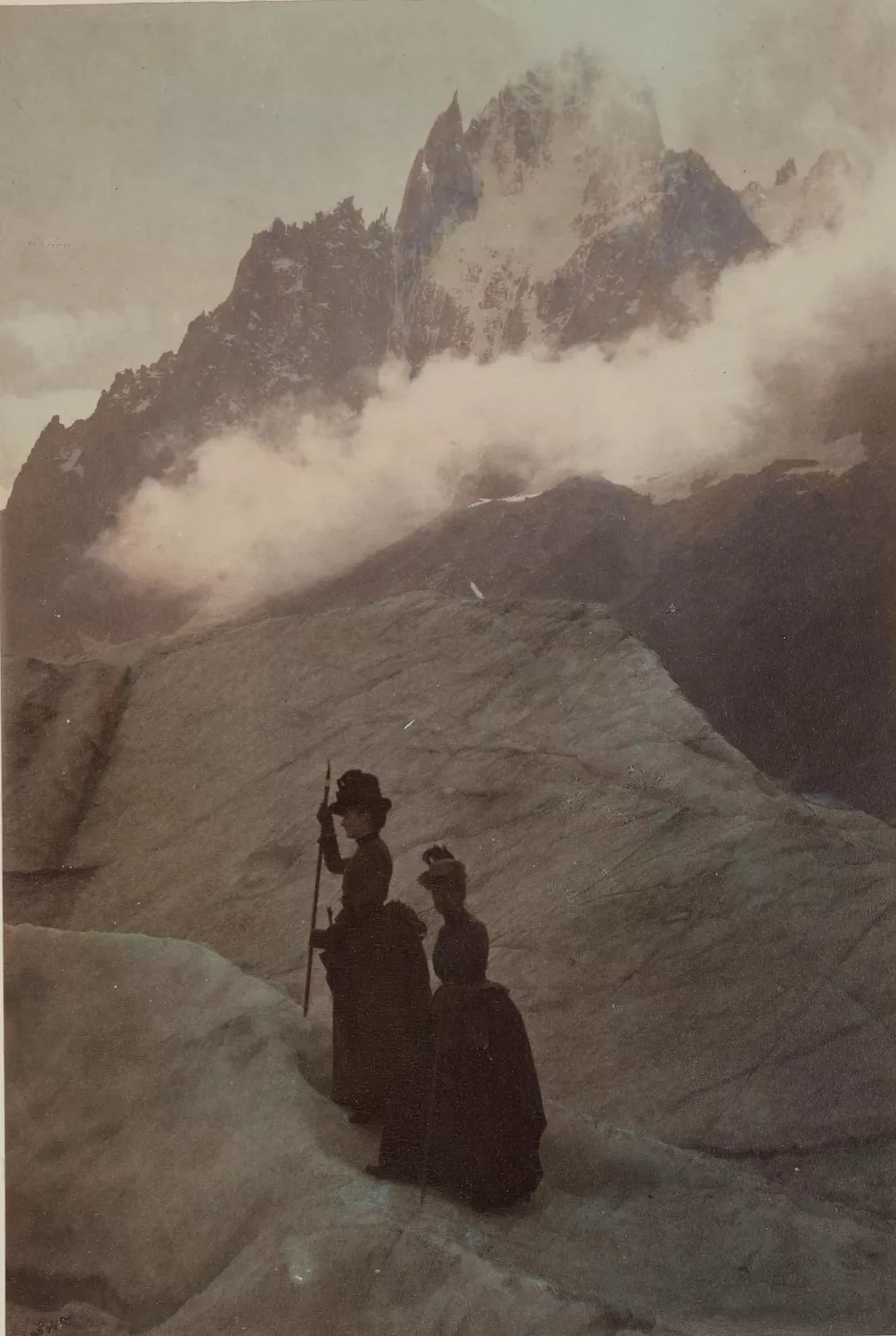

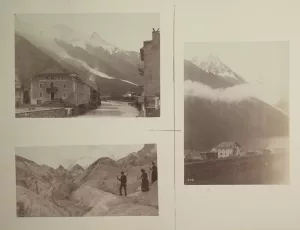

J. A. Chain, The Chain gang abroad: around Europe with a Camera, 1888, Photograph album containing 274 mounted albumen prints, many with hand-coloring, 16 3/20 x 20 17/20 in. (41 x 53 cm), Princeton University Library

Women are not usually seen as the heroes and protagonists of the American West and its landscape, especially in myth and art.

The late nineteenth century quote and directive often attributed to Horace Greeley, “Go West, young man, go West and grow up with the country,” epitomizes this stereotype. The country actively encouraged men to be the leading figures of the Western story. Renowned male artists of the West, such as Frederic Remington (1861-1909) and Charles Russell (1852-1916), furthered this view through their dramatic depictions of fearless cowboys in paint and bronze. Later, it was John Wayne’s masculine cowboy silhouette that symbolized the West.

Utah and Colorado women artists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, though, challenge these myths. Their paintings and photographs complicate the stories we tell about the Rocky Mountains, the Western landscape, and women’s place therein.1 Their works and careers reveal that the American West was never the simple, masculine rugged frontier that lives large in the American conception, but something layered, nuanced, and multi-gendered.

Helen Henderson Chain, Royal Gorge on the Arkansas River, 1890, Oil Painting on canvas, 43 × 22 in. (109 × 58.9 cm), Courtesy History Colorado, Courtesy History Colorado-Denver, Colorado

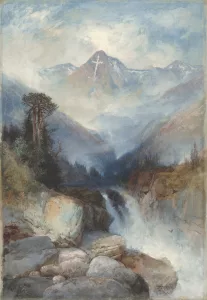

Thomas Moran, Mountain of the Holy Cross, 1890, watercolor and gouache over graphite on blue laid paper, 17 13/16 × 12 3/8 in. (45 × 31 cm), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

J. A. Chain, The Chain gang abroad: around Europe with a Camera, 1888, Photograph album containing 274 mounted albumen prints, many with hand-coloring, 16 3/20 × 20 17/20 in. (41 × 53 cm), Princeton University Library

J. A. Chain, The Chain gang abroad: around Europe with a Camera, 1888, Photograph album containing 274 mounted albumen prints, many with hand-coloring, 16 3/20 × 20 17/20 in. (41 × 53 cm), Princeton University Library

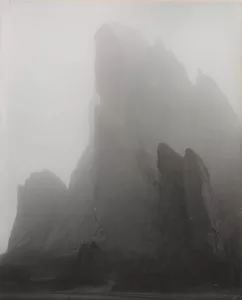

Laura Gilpin, Ghost Rock, 1919, Platinum print, 9 5/8 × 7 9/16 in. (24.5 × 19.2 cm), © 1979 Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas

Alfred Stieglitz, The Dying Chestnut, 1919, Gelatin Silver Print, 9 ½ × 7 ½ in. (24 × 19 cm), The Art Institute of Chicago

Helen Henderson Chain’s (1849-1892) dramatic and romantic landscape paintings specifically demonstrate this complexity. Her works such as Burros on the Trail (1870–1890) and Old Miners Cabin (1885) follow the stylistic traditions of the Hudson River School painters who came west, like Thomas Moran (1837-1926) and Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902). These artists and their contemporaries created the template for how the West was to be painted—dramatic, romantic, godly. H. Henderson Chain followed their example, painting dramatic vistas that emphasize diagonal lines, large expansive spaces, and the smallness of the humans who inhabit them.2

While doing this, she climbed and explored the mountains of Colorado alongside her husband, subverting the idea that it was only men who could paint the drama of the West.3 In photographs she took in Europe, H. Henderson Chain and other women are seen traversing the landscapes in long dark dresses, hiking poles in hand. Her self-documentation as a mountain climber and artist further destabilize an imagined West where only men are free to explore.

Laura Gilpin (1891-1979), active in Colorado and New Mexico a few decades after H. Henderson Chain, is another figure that exemplifies these nuances. Photography, like landscape painting, was male-dominated in the early twentieth century—and especially those who took cameras to desolate and rugged landscapes, were assumed to be men. But L. Gilpin, who was gifted a Kodiak Brownie camera on her twelfth birthday, became one of the most important photographers of the American West. Her photographs capture the drama of the landscape, yet with a pictorial softness and painterly quality.

The Ghost Rock. Garden of the Gods (1919) illustrates L. Gilpin’s use of pictorialism, a style that aimed to make photographs look more like paintings. In this composition, L. Gilpin captures the sharp rugged and dangerous cliffs in a black and white haze, their sharpness dulled by the way L. Gilpin photographed them. Her photos of the Grand Canyon also show a softer, more composed perspective of the vast landscape. She homes in on the details, brings the composition in together, and emphasizes the textures, lines, and shapes in her scenes, in ways that contrast to the modern, crisp style of later photographers of the West, including Ansel Adams (1902-1984).

Like H. Henderson Chain’s paintings, L. Gilpin’s photographs can be read simultaneously as masculine and feminine. That L. Gilpin was taking her camera and shooting the western landscape, traversing these dangerous areas, was seen as a masculine act in and of itself—then complicated by the pictorial way in which she captured it.

Her photo Work in the Garden of the Gods (1920) further shows the nuance of gender in the American West—men and women sit under the shadow of a towering cliff, painting en plein air. Her composition directly contradicts the myth of the lonesome cowboy in these spaces. As a lesbian woman in a long-term queer relationship, L. Gilpin’s own biography further challenges assumptions about gender and art in the American West.4

As Colorado and Utah moved into the Progressive and New Deal Eras of the 1920s and 1930s, their cultures and the artworks the women living there created took a turn toward the modern. These periods both brought a focus on bettering society and creating more support for women, children, and families throughout the United States.5 This oftentimes included more support for the arts and artists through programs like the WPA and the founding of art institutions, organizations, and societies.6

There was a sense of hope coming also from women’s suffrage, in the United States passed at the national level in 1920.

Artists started to paint the landscape with fresh eyes and approaches—influenced by the trends of modernism that came out of Europe at the turn of the century and then spread to artists around the world, including in the U.S. The compositions are tighter, emphasizing shape, imagined color, line, and texture more than the vastness and largeness of the landscape. Artists such as Utah’s Mabel Frazer (1887-1981), Louise Richards Farnsworth (1878-1969), and Florence Ware (1891-1972), and Colorado’s Elisabeth Spalding (1868-1954) and Annie Van Briggle Ritter (1868-1929), embraced new ways of thinking about and depicting the West, using vibrant, dynamic landscapes to reflect cultural optimism, mobility, and reform.

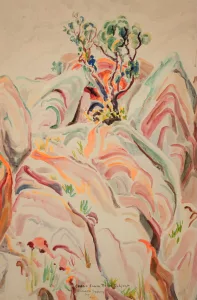

Elisabeth Spalding, Cedar from Rock Subject (Colorado), 1929, 30 × 20 in. [76.2 × 50.8 cm], watercolor on paperboard, Denver Art Museum/Kirkland Museum of Fine and Decorative Art

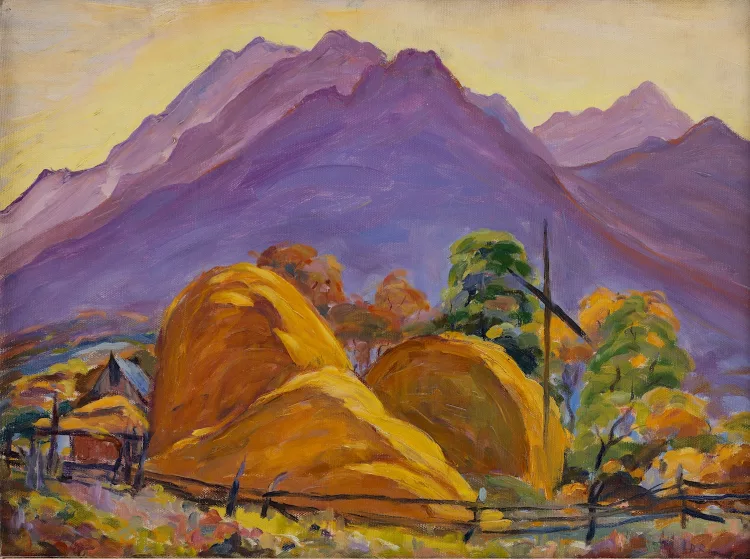

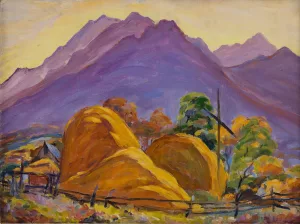

Louise Richards Farnsworth, Hay Stacks, 1935, oil on board, 18 × 24 in. [45.7 × 61 cm], Springville Museum of Art

Anne Van Briggle Ritter, Rising Thunderheads, 1926, oil on board, 18 × 21 ½ in. [45,7 × 54,6 cm], Denver Art Museum/Kirkland Museum of Fine and Decorative Art

Elisabeth Spalding, Castelorosso. Rock of Asia Minor Shore, 1934, watercolor, 9.5 × 12.5 in. [24,1 × 31,8 cm], Denver Public Library

Florence Ware, Wasatch Mountains, n.d., oil on canvas, Springville Museum of Art, Gift from Rodney and Bonnie Moore

E. Spalding’s Cedar from Rock Subject (Colorado) (1929) embodies these changes. Instead of emphasizing the vast grandeur of the Colorado Rockies, Spalding places a lone tree at the center of her composition, the multicolored layers of rock radiating out beneath it. In L. Richard Farnsworth’s Haystacks (1935), the mounds of bright yellow cut hay are as physically and visually dominant as the purple Wasatch Mountains in the background.

Their paintings emphasize movement, the play of light and shadow, and an overall brightness and modern sensibility to the land in the west. They stand in sharp contrast to the daunting and impenetrable wilderness of the nineteenth-century Hudson River School depictions. These bold colors and undulating lines paint the Utah and Colorado mountains and desert as something modern, fresh, and hopeful.

In Utah, Alice Merrill Horne (1868-1948) was a leading figure in the progressive movement—advocating for better arts funding and support, children’s health, and other humanitarian causes. It was her advocacy and work as a state legislator that created the first state arts agency in the United States, the Utah Art Institute, in 1899. Her influence and philosophy in Utah tied beauty and art to both moral and spiritual growth, and she worked tirelessly to support and advocate for Utah artists.7 For Horne, and other devout members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (most commonly known as the Mormon Church), this was not only a moral and civic duty, but a uniquely devotional one. Horne was the leader of a group of women, and other artists in Utah, who saw the creation of and advocacy for art and beauty as a way to spread and practice their religious beliefs.8

In Mormon Utah, where women were expected to prioritize family roles, art also offered a socially acceptable path to prominence, even for non-Mormon women like Florence Ware (1891-1972). Art was a kind of loophole to these cultural limitations. Because it could deal with beautifying the home, or capturing the beauty of God’s nature, it was seen as a “safe” realm for women to gain some prominence, power, and prestige as public advocates and community leaders for the arts. Through their artistic output and administrative duties in academia or in arts institutions and organizations, these women sought, and in many ways obtained, more freedom and independence. Their civic leadership and institutional influence challenged the myth of women as passive figures on the frontier; they were not merely subjects of the story of the American West, but active shapers of its cultural and social landscape.9

The women also traveled significantly, throughout the western United States and beyond, contradicting the idea that their world was static and in one place. Many of the women artists studied in Paris, or in the eastern United States, at the Art Institute of Chicago or Students League of New York for example, and traveled extensively throughout Europe. They often took what they learned in these formal settings back home and translated it for local audiences. Louise Richards Farnsworth (1878-1969) grew up in Utah but moved to New York as a young woman. Her work was lauded back East for capturing the landscape of the West and its spirit.10 Mabel Frazer (1887-1981) studied in Chicago and later in Italy, and traveled extensively throughout the southwest. She was often quoted talking about the importance of the Western land to her work.11 This mobility contradicted the image of the isolated, provincial Western woman, revealing instead a generation of artists who were cosmopolitan and modern while still deeply engaged with the Western landscape.

Together these artists show us that the West and its landscape cannot be neatly divided into masculine and feminine; or wild and civilized; it is always both. The dominant narrative likes to imagine the West as monolithic, but these women and their work show it was never that simple. Their artwork and depictions of the West dismantle its story as a singular male domain. Notably, as white women, their work and this deconstruction has limits. The complexities of settler colonialism, borderlands, and racism are largely absent from their work, as are, for the most part, Native American peoples and their communities (the exception in this particular group of artists may be L. Gilpin, who spent significant time photographing Navajo people).12 Their art does not usually challenge the racial myths that dominate how the West has been understood and portrayed. Despite this, their art reveals some of its complexity rather than its myth.

There is much written on myth, art, and women in the American West that influences this essay. For further reading see: William Truettner, The West as America: Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier, 1820–1920 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991), Henry Nash Smith, Virgin Land: The American West as Symbol and Myth (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1950), William H. Goetzmann and William N. Goetzmann, The West of the Imagination (New York: Norton, 1986), reprinted by University of Oklahoma Press in 2009; Patricia Trenton, Independent Spirits: Women Painters of the American West 1890–1945 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996); Virginia Scharff and Carolyn Brucken, Home Lands: How Women Made the West (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010); Heather Belnap and James R. Swensen, “Women and the Arts in Twentieth Century Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 91, no. 4, special issue (2023).

2

For more on Henderson Chain see Deborah A. Wadsworth, Helen Henderson Chain: Art & Adventure in Early Colorado(Denver: Denver Public Library, 2014).

3

For further context, see Barbara Cutter, “‘A Feminine Utopia’: Mountain Climbing, Gender, and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth-Century America,” Journal of Women’s History 33, no. 2 (Summer 2021): 61–84.

4

For more on Gilpin and queerness, see Louise Siddons, Good Pictures Are A Strong Weapon: Laura Gilpin, Queerness, and Navajo Sovereignty (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2024).

5

For information on suffrage and these eras see: Colleen McDannell, Sister Saints:Mormon Women Since the End of Polygamy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019); Rebecca Mead, How the Vote Was Won: Woman Suffrage in the Western U.S., 1868–1914 (New York: New York University Press, 2004); Patricia Lyn Scott and Linda Thatcher, Women in Utah History: Paradigm or Paradox (Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, 2005); R. Todd Laugen, The Gospel of Progressivism: Moral Reform and Labor War in Colorado, 1900-1930 (Denver: University Press of Colorado, 2010).

6

Part of the hopefulness these women could feel and achieve came in part because they were white and middle or upper middle class. Racial and class divides further complicate the conception of the American West that is discussed in this essay. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) was an American New Deal agency, created in 1935 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, which employed millions of jobseekers to carry out public works projects and provided jobs in the arts during the Great Depression. The agency was responsible for building infrastructure, but also supported numerous art projects.

7

For more on Horne’s ethos and contributions, see Alice Merrill Horne, Devotees and Their Shrines: A Handbook of Utah Art (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1914) and Harriet H. Arrington, “Alice Merrill Horne,” in Worth Their Salt: Notable But Often Unnoted Women of Utah, ed. Colleen K. Whitley (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1996).

8

See Heather Belnap, “Aesthetic Evangelism, Artistic Sisterhood, and the Gospel of Beauty: Mormon Women Artists at Home and Abroad, circa 1890-1920, in Mormon Women’s History: Beyond Biography ed. Rachel Cope, Amy Easton-Flake, Keith A. Erekson, and Lisa Olsen Tait (Lanham, Maryland: Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 2017).”

9

For more on women shaping the Utah art world, see Emily Larsen, “The Power of Paint,” Utah Historical Quarterly 91, no. 4 (2023): 269–283.

10

See “Critics Acclaim Artistry of Utah Women Painter,” The Salt Lake Tribune, April 28, 1934.

11

In 1932, she said, “I have always said that great art could not be borrowed or transplanted; it must have roots deep in a native soil.” Salt Lake Tribune, 2 October 1932. For more on Frazer, see James R. Swensen, “A Tyrannical Grace,” Utah HIstorical Quarterly 91, no. 4 (2023): 302–314.

12

See Carlyle Schmollinger, “An Enduring Force: The Photography of Laura Gilpin among the Twentieth-Century Navajo,” The Thetean: A Student Journal for Scholarly Historical Writing 42, no. 1, Article 9 (2013).

Emily Larsen is Director of the Springville Museum of Art, one of Utah’s oldest visual arts organizations and a champion of Utah artists. She holds degrees from Brigham Young University and the University of Utah, and has published and presented widely on Utah’s cultural heritage. A passionate advocate for the power of art to shape communities and inspire connection, she also serves on the boards of the Utah Historical Society, Artists of Utah, and Epicenter. She is co-authoring, with Dr. Heather Belnap, a forthcoming book on women and Utah art, c.1880–1950.

Publication as part of the exhibition Women Artists of the American West: Trailblazers at the Turn of the 20th Century

Emily Larsen, "Women Artists: Reframing the Rockies." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/artistes-femmes-recadrer-les-rocheuses/. Accessed 5 March 2026