Research

Louise-Joséphine Sarazin de Belmont, Vue du château de San Giuliano, près de Trapani, Sicile, c. 1824-1826, oil on canvas, 22.9 × 29.9 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington

Sofonisba Anguissola, Portrait Group with the Artist’s Father Amilcare Anguissola and her Siblings Minerva and Astrubale, c. 1559, oil on canvas, 157 × 122 cm, Nivaagaards Malerisamling, Copenhague

Books presenting an overview of the landscape art, whether in painting, printmaking or drawing, contain few mentions of female artists and frequently overlook them altogether when it comes to eras preceding the 20th century. This oversight is rarely noted or explained. It may nevertheless be useful to explore the issue by looking back at earlier eras and examining the historiography of art; indeed, what is missing can often be just as intriguing as what is present.

Let us begin with Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects by the artist and writer Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574). The first two editions of this book – published in 1550 and 1568, respectively – differ in some respects. In “A Hand More Practiced and Sure”: The History of Landscape Painting in Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists’, the art historian Karen Hope Goodchild demonstrates that the author’s discussion of the landscape is considerably more developed in the 1568 edition, which hints at the genre’s growing importance in the arts.1 Accused of Tuscan chauvinism, G. Vasari also adds a number of northern European artists to this new edition. But while he praises their skills, he references landscape painting to argue that 16th century Italian artists surpass them. He further expands it by mentioning a few women artists, in addition to Properzia De’ Rossi (1490–1530), whom he has already discussed in the 1550 version. He is silent when it comes to their landscapes, yet he does admire canvases by Sofonisba Anguissola (c. 1532–1625) that include background landscapes, a feature he highlights and extols in work by some of his countrymen. He had the opportunity to view her Portrait Group with the Artist’s Father Amilcare Anguissola and her Siblings Minerva and Astrubale (c. 1559) at her father’s home and mentions it in his book, although he does not discuss the mountains visible behind the sitters.2

A century later, in 1667, the French architect and art theorist André Félibien explained the hierarchy of genres as follows: “Thus he who paints fine Landscapes, is above him who only paints Fruits, Flowers, or Shells: He who paints after Life is more to be regarded than he who only represents still Life; and as the Figure of a Man is the most perfect Work of God upon Earth, it is also certain that he who imitates God in painting human Figures is by far more excellent than all others”.3 The still life clearly occupied the lowest position in the hierarchy. At the top was history painting, which required a solid command of the human anatomy gained by drawing live models. This type of practice was less accessible to women, which effectively restricted them to painting scenes without human figures.

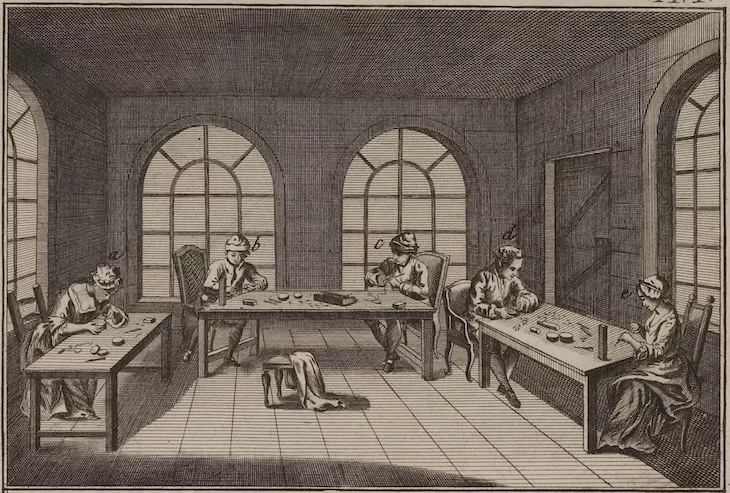

Is this why a “gender-based division of artistic labour”4 became the norm in family-run studios, the women primarily painting backgrounds featuring landscapes and architecture? The sociologist Séverine Sofio references this division in eighteenth-century painters’ and sculptors’ guilds, but it may also have been common in academician artist dynasties such as the Boullogne (or Boulogne) family, which A. Félibien discusses in his Entretiens sur les vies et sur les ouvrages des plus excellents peintres anciens et modernes (Conversations on the Most Excellent Painters, Ancient and Modern). In particular, he praises Geneviève (1645–1708) and Madeleine Boullogne (1646–1710), who executed the ‘ornaments’5 of a decorative ensemble that their father Louis Boullogne (1609–1674) made for the chamber of Antoine Le Menestrel, chief court usher of France and treasurer of public buildings.

Female academicians such as G. and M. Boullogne were rare at this time; the sisters were among only three women to exhibit works at the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture’s 1673 salon (one of its first). The salon booklet mentions G. Boullogne’s painting, a landscape whose current location is unknown; it may have been destroyed, like the rest of her works. It was the last landscape by a woman to appear at the salon until 1791, apart from paintings that were not ‘pure’ landscapes, such as A Hound with Dead Game in a Landscape, exhibited in 1787 by Anne Vallayer-Coster (1744–1818).

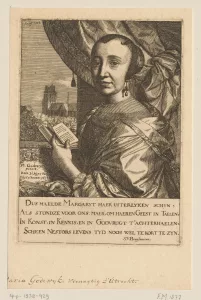

Samuel van Hoogstraten, La poète et peintresse Margaretha van Godewijk près d’une fenêtre donnant sur la Grande Église Notre-Dame à Dordrecht. Sous le portrait, un texte de quatre lignes en néerlandais, 1677, gravure, 17.4 × 12.8 cm, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Joanna Koerten, Vierge à l’Enfant avec saint Jean, c. 1703, cut paper, 6.98 × 5.71 cm, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Margaretha de Heer, Un chou rouge, un escargot, un papillon, une libellule, une abeille et un cloporte dans un paysage, undated, oil on wood, 39.4 × 29 cm, © Kunsthaus Zürich, Vereinigung Zürcher Kunstfreunde, 2013

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when it came to academicians of either gender, one could not see the forest for the trees, so to speak. An entire less ‘exhibited’ world existed in France and other countries. In other words, women landscape artists may very well have been working in these non-academic environments, but identifying them today is difficult due to their lesser visibility. In the northern Netherlands, due to various factors, women artists appear to have benefitted more from the seventeenth century’s opulence and landscape art flourished there. The Dutch painter and biographer Arnold Houbraken (1660–1719) highlighted some of them his nostalgic Groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen [The Great Theatre of the Netherlandish Painters and Paintresses, 1718-1721] inspired by Introduction to the Higher Academy of the Art of Painting: or The Visible World (1678) by the artist and theorist Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627–1678). The mere fact that A. Houbraken referred to women artists in his book’s title is revealing.

Another important detail is that A. Houbraken and S. van Hoogstraten themselves both painted landscapes. In their respective publications, they also both mention the landscape paintings and embroideries of Margaretha van Godewijk (1627–1677). A. Houbraken furthermore references Joanna Block, née Koerten (1650–1715), whose body of cut-paper pieces included landscapes, although few traces of them remain. But the seventeenth-century Netherlands saw other women landscape artists who went unmentioned by A. Houbraken. Examples include Margaretha de Heer (c. 1603–between 1659 and 1665, who was married to Andries Pieters Nyhoff), and Catharina van Knibbergen (active between 1630 and 1660), although it is difficult to learn anything more about them. However, the art market’s renewed appreciation for women artists of the past is helping bring their works back into prominence and facilitating the determination of rightful attributions.

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Vue du lac de Challes et du Mont Blanc, 1807-1808, pastel blue-grey paper, 40.64 × 51.75 cm avec le cadre, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis

Catherine Edmée Simonis Empis, née Davésiès de Pontès, Vue de la forêt de Pongibaud (Auvergne) ; paysage historique (Histoire de Brachim, de Grégoire de Tours), 1842, oil on canvas, 198 × 256 cm (avec cadre), musée du Louvre, Paris

Did women art historians, or rather their precursors, speak more about women landscape artists than their male counterparts? This does not seem to have been the case, judging from Plumes et pinceaux. Discours de femmes sur l’art en Europe (1750-1850). Anthologie (Pens and Brushes: Women’s Discussions of Art in Europe) (2012), edited by Mechthild Fend, Melissa Hyde and Anne Lafont. For the period in question, some female authors like Germaine de Staël, Félicité de Genlis, Alida de Savignac and Marianne Colston write about landscape paintings but mention only male artists, who seem to be the only ones they know or value.

Yet in the late 18th and early 19th century, women artists practiced landscape painting with passion and sometimes found success in it – those from France include Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842), Louise-Joséphine Sarazin de Belmont (1790–1870) and Catherine Edmée Simonis Empis, née Davésiès de Pontès (1796–1879). F. de Genlis, however, was aware of the difficulties women artists faced: “If a painter intends to instruct his daughter in his art, he never conceives the project of making her a painter of history, but will continually repeat, she should attempt only to paint portraits, miniatures, or flower-pieces. Thus is she discouraged, and thus is the fire of her ambition stifled; she paints roses; she was born, perhaps, to paint heroes!”6 This diatribe contains no mention of landscapes or genre painting. Did flowers sum up the genres of still life and landscape ? Were they forgotten? Or were they intentionally omitted – and why?

Over the course of the nineteenth century, the dogma of genre hierarchy fell away. At the same time, the number of women artists rose considerably. Two women exhibited landscapes at the Paris Salon in 1791, four in 1817, fourteen in 1845, forty-nine in 1877 and seventy-two in 1907. But no women landscape artists appear in Charles Baudelaire’s Salons of 1845, 1846 or 1859 or in John Ruskin’s 1843 Modern Painters: Their Superiority in the Art of Landscape Painting to All the Ancient Masters.

If we turn to the latter half of the nineteenth century, women landscape artists are finally mentioned in an art history publication – albeit in a female-only context – in Women Painters of the World, from the Time of Caterina Vigri, 1413–1463, to Rosa Bonheur and the Present Day (1905), edited by the Welsh art critic Walter Shaw Sparrow. Yet W. S. Sparrow summarised women’s relationship to the landscape as follows: “Women have seldom been drawn in art to nature in the woods and fields. The gentler sex, as a rule, has not appreciated landscapes.”7 He appears to echo a gender stereotype that took hold or gained strength in various circles over the nineteenth century: namely, that apart from a few exceptions, women did not like rural landscapes. As for urban landscapes, there is no question of them.

This may explain the absence of women artists from twentieth-century reference works such as Kenneth Clark’s 1949 Landscape into Art. Later, in Signs of Recovery: Landscape Painting and Masculinity in Nineteenth-Century France (2000), Steven Adams shows how critics and theorists outlined the archetype of a “virile but child-like landscape painter”.8 captivated by a nature imbued with feminine qualities. What place might women landscape artists have held in this history, in the highly gendered, heteronormative society of the nineteenth century? What history of landscape art could have been written, with such a legacy and before the emergence of research on connections between gender and the landscape, if not one that omits women artists entirely?

Karen Hope Goodchild, ‘“A Hand More Practiced and Sure”: The History of Landscape Painting in Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists’, Artibus et Historiae, no. 64, January 2011, pp. 25-40.

2

Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, vol. 5, trans. Gaston du C. de Vere, London: MacMillan & Co., Ltd, 1913, p. 128.

3

André Félibien, Seven conferences held in the King of France’s cabinet of paintings, trans. anonymous, London, 1740, xxvi–xxvii.

4

Séverine Sofio, Artistes femmes, la parenthèse enchantée. XVIIIe–XIXe siècle, Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2016, p. 30.

5

André Félibien, Entretiens sur les vies et sur les ouvrages des plus excellens peintres anciens et modernes, avec la vie des architectes, Imprimerie de S. A. S., 1725, vol. 4, p. 311.

6

Félicité de Genlis, Tales of the Castle, or Stories of Instruction and Delight, trans. Thomas Holcraft, 9th ed., London, 1785, pp. 202–203.

7

Walter Shaw Sparrow, Women Painters of the World, from the Time of Caterina Vigri, 1413–1463, to Rosa Bonheur and the Present Day, London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1905, p. 59.

8

Steven Adams, ‘Signs of Recovery: Landscape Painting and Masculinity in Nineteenth Century France’, in Steven Adams and Anna Gruetzner Robins (ed.), Gendering Landscape Art, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000, p. 14.

Marie Gord is head of research and documentation at the Louvre-Lens. She developed an interest in landscape painting while researching symbolist landscapes in Lombardy during her art history studies. A co-curator of the exhibition Paysage. Fenêtre sur la nature (The Landscape: A Window on Nature) (March–July 2023, Louvre-Lens), she authored an essay titled ‘Peintresses et paysages: l’art de faire tapisserie’ (‘Women Painters and Landscapes: The Art of Making a Tapestry’), examining women’s absence from the history of landscape painting, for the catalogue.

Marie Gord, "Women Artists and the Landscape in the West: Critical Misfortune." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/linfortune-critique-des-peintresses-de-paysage/. Accessed 13 February 2026