Research

Louise-Joséphine Sarazin de Belmont, Selbstbildnis Sarazin de Belmont, Louise Josephine, Landschaftsmalerin [Self-portrait of Louise-Joséphine Sarazin de Belmont, landscape painter], 1849, graphite on paper, 16.7 x 20.4 cm, Kupferstich-Kabinett, Dresde

According to the art historian Linda Nochlin, from the Renaissance to the 19th century, women artists seldom had the opportunity to draw nude models, a practice considered essential for developing one’s skills. This led women to restrict themselves “to the ‘minor’ fields of portraiture, genre, landscape, or still life.”1 But paradoxically, very few women landscape painters working before 1850 are to be found in the historiography of landscape art.

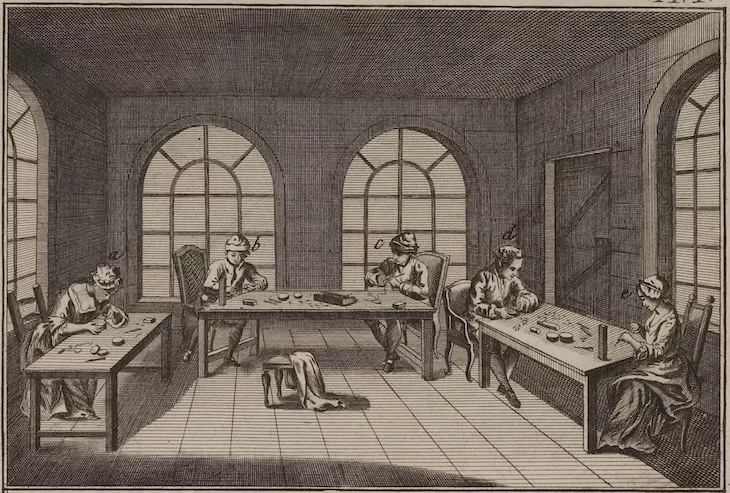

In 17th-century France, women had to contend with the misogyny of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, which also placed landscapes low in the genre hierarchy. Yet this dual contempt for the landscape and women artists was not the same from one European country to the next. Moreover, current research suggests that over the course of Louis XIV’s reign (1643–1715), landscape painting gradually freed itself from its classification as a secondary, ornamental genre.2 Women do not seem to have played a major role in this shift, however. Art courses offered by the Académie, the École royale des élèves protégés and, to a lesser extent, the various free drawing schools founded in Paris and other French cities in the 18th century generally prohibited women (the École gratuite de dessin pour les jeunes personnes de Paris was created only in 1803). This meant that training in the family circle or in private studios were often the sole options available to women. And for this to be possible, they usually had to belong to a family of artists. In trade guilds, women often enjoyed a more favourable status, but the gender-based division of labour in families – which led women to paint backgrounds and therefore landscapes, amongst other features – undoubtedly prevented them from identifying their contributions.

Claudine Bouzonnet-Stella, La culture des jardins et la greffe des arbres fruitiers, d’après Jacques Stella, 1650-1674, etching, burin, laid paper, 24.6 x 31 cm, musée des beaux-arts, Orléans

Geertruydt Roghman, ‘t Huys te Zuylen [The House in Zuylen], d’après Roeland Roghman, 1646-1647, etching, paper, British Museum, London

Some 17th-century landscapes known to have been made by women are copies or interpretations of works by men in the circles of these women artists. While men, in the West, were associated with creation, women were often confined to a reproductive role – in all senses of the term. That said, it must be remembered that originality was not yet a major criterion in the evaluation of artwork. Examples of this practice include the prints Claudine Bouzonnet-Stella (1636–1697) made after works by her uncle Jacques Stella (1596–1657) and, many years later, those of Jeanne Françoise Ozanne (1735–1795) after drawings by her brother Nicolas Marie Ozanne (1728–1811). Women artists furthermore often combined various approaches, producing original works, interpretations and copies. In the northern Netherlands, Geertruydt Roghman (c. 1625–1657) produced an intriguing body of work that can be divided into two types: one consisting of prints of landscapes drawn by her brother, Roeland Roghman (c. 1627–1692), amongst others, and another made up of original works depicting women occupied with domestic tasks in indoor spaces.

This dichotomy reflects a gender stereotype that cuts across both time and geography: women’s confinement to domestic and interior spaces had significant consequences for landscape art, especially since the practice of drawing – and later painting – en plein air studies intensified in the 17th and 18th centuries, respectively. The media women artists used were closely tied to the domestic sphere. They did not always work with oil on canvas but sometimes chose more fragile, delicate media – drawing, cut paper and embroidery – incorporating readily available materials that women were routinely taught to use. An excellent example of this is Landscape after Painting by Salvator Rosa by Mary Linwood (1755–1845).3 Works made with such media are challenging to preserve and have unfairly been perceived as crafts rather than art. However, researchers have recently begun reevaluating them, studying them from the new perspectives in human sciences and art criticism and, like the art historian Andrea Pappas, opening new avenues for interpretation.4

Margareta de Heer, Stilleben med landskap [Still life with landscape], undated, watercolor and gouache on parchment, 46.5 x 47.5 cm with frame, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

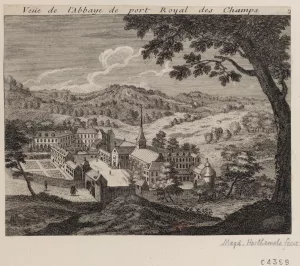

Louise-Magdeleine Horthemels, Veüe de l’abbaye de Port-Royal des Champs, between 1710 and 1713, for original engraving, etching, burin, paper, Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Estampes et photographie, Paris

Landscapes by women artists were frequently part of a production which wasn’t specialized in landscape; they were generally only occasional landscape artists, which makes them less visible to landscape historians today. This is the case, for instance, for Louise-Magdeleine Cochin, née Horthemels (1686–1767) and her series of prints of the Abbey of Port-Royal des Champs, which includes several landscape views likely inspired by various artists. The same goes for Anna Maria de Koker (active in the 17th century, died in 1698), best known for her poems than for her landscape engravings. ‘Paintresses’ and female printmakers who specialised in still lifes or portraits occasionally made landscapes, although these often remained in the shadows since the artists were usually known for only one type of work. One such example is the Dutch artist Margaretha de Heer (c. 1603–between 1659 and 1665), best known for her studies of insects and plants. Her landscapes are so impressive that they have sometimes been attributed to an atypical landscape painter, Hercules Seghers (c. 1590–c. 1638). They appear to be hybrids of the still life and landscape genres; worthwhile insights could be gained from examining them with the approach used by art historian Estelle Zhong Mengual for a work by Martin Johnson Heade (1819–1904): she champions an environmental vision of art history, in which “a study of Western landscape painting is entwined with facets of natural history”.5 This would allow us to more objectively view both the nature-culture dialectic underpinning the genre hierarchy and the marginalisation of women associated with the idea of nature. The philosopher Carolyn Merchant discusses this latter phenomenon in The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology and the Scientific Revolution (1980). Conversely, it may also be useful to explore potential connections between these landscapes and the illustrations in contemporary Dutch emblem books (such as those by Jacob Cats), which played a role in women’s education.6

Simon Denis, Les Cascatelles de Tivoli, avec Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun dessinant, 1790, oil on panel, 48.3 × 62.1 cm, Collection Frits Lugt, Fondation Custodia, Paris

Jean-Baptiste-Marie Pierre, Une jeune femme peignant un paysage, dite « L’Artiste » ou Portrait présumé de MargueriteLecomte, c. 1770, sanguine, Private collection, © Christie’s Images / Bridgeman Images

In France, women artists seemed to internalise the genre hierarchy. In her memoirs, written in the early 19th century, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842) frequently mentions her love of landscapes and her intensive drawing practice in this genre, but does not describe herself as a landscape artist. However, she readily uses this term for men, such as her friend Hubert Robert (1733–1808), whose portrait she painted in 1788. She also recounts an excursion made with Simon Denis (1755–1813) and François-Guillaume Ménageot (1744–1816) to draw the Tivoli waterfalls. S. Denis left behind interesting pictorial records of this outing. The studies É. Vigée Le Brun produced that day undoubtedly had an impact on her work, for instance the background of Portrait of Countess Maria Theresia Bucquoi, née Parr (1793, Minneapolis, Minneapolis Art Institute). Despite this, É. Vigée Le Brun laments her choice to limit herself to portraiture – notably for financial reasons – and regrets not using her time “to make a few paintings with subjects that inspired [her]”.7 The word ‘subjects’ is probably a reference to history painting or genre scenes. She seems to overlook the landscape.

É. Vigée Le Brun belongs to the first of three generations of French women artists that the sociologist Séverine Sofio identifies in what she calls the ‘enchanted parenthesis’ – the period between 1750 and 1850. The second generation, which trained from the early 19th century to around 1820–1825, included women who did not belong to art dynasties but made a name for themselves at the Salon in the field of landscape painting, working exclusively in this genre. One of them was Catherine Edmée Simonis Empis, née Davésiès de Pontès (1796–1879). At this time, Louis-Étienne Watelet’s (1780–1866) landscape art workshop offered landscape art classes for women, a rare opportunity for them to learn landscape painting outside their family circles; amongst others, he taught C. Empis.8 In this same generation, Louise-Joséphine Sarazin de Belmont (1790–1870) trained under Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes (1750–1819), zealot of the historical landscape genre. Landscape drawings and paintings had previously been considered ornamental arts by the 18th-century upper-class to make women more attractive on the marriage market. This bias undoubtedly had a negative impact on evaluations of their work. In around 1770, Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre (1714–1789) drew a young woman working on a landscape painting. Was she an artist or an ‘enthusiast’? With the generation of C. Empis and L.-J. Sarazin de Belmont, landscape art became a socially acceptable way of earning a living, especially given that many were interested in acquiring such works. This development is evident from the publication of many drawing instruction books – for example Le Dessin sans maître, méthode pour apprendre à dessiner de mémoire (Drawing without a master: learning to draw from memory) by Marie-Élisabeth Cavé, née Blavot (1810?–1882), published in 1850 – and from the growing number of portraits and self-portraits of women landscape artists. Those who were married seemed to be championed by their spouses. In the 19th century, for example, Laure Brice’s husband pleaded her cause to the director of French museums in 1837, and Sophie Vincent-Calbris (1819–1859) was married to a man who is believed to have adopted her family name.9

Anne Brontë, Woman gazing at a sunrise over a seascape, 1839, pencil on paper, Haworth, Brontë Parsonage Museum

Finally, the landscape is an instrument for appropriation, both symbolic (especially via art) and tangible, especially where real estate is concerned, the history of women’s access to landownership must be considered for a full appreciation of fluctuations in their landscape art. In England, an unexpected source of insights into these issues of appropriation is the novel The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, published in 1848 during the Springtime of Nations by Anne Brontë (with the pseudonym Acton Bell), whose brother Branwell and sister Charlotte had begun careers as painters. The story takes place mainly in the 1820s. Its protagonist, Helen Graham, an occasional portraitist, becomes a professional landscape painter to free herself and her son from her abusive husband. She ultimately gains her freedom and becomes a landowner.10 Considered scandalous in its time, this novel draws readers into the tensions between the picturesque and the sublime, and between Romanticism and realism, from a point of view cognisant of gender inequalities.11 It serves as subtle confirmation of how the broader field of landscape art history can benefit from a history of landscape art informed by gender studies and intentionally incorporating women landscape artists.

Linda Nochlin, Women, Art, and Power and Other Essays, Boulder: Westview Press, 1988, p. 160.

2

Hugo Coulais, L’Éveil du paysage. Peindre la nature sous le règne de Louis XIV, doctoral thesis supervised by Christine Gouzi, Paris: Sorbonne Université, 2022.

3

Theresa Kutasz Christensen, ‘Mary Linwood’, AWARE, 2024, https://awarewomenartists.com/artiste/mary-linwood/.

4

Andrea Pappas, Embroidering the Landscape: Art, Women and the Environment in British North America, 1740–1770, London: Lund Humphries, 2023.

5

Estelle Zhong Mengual, Apprendre à voir. Le point de vue du vivant, Arles: Actes Sud, 2021, p. 26.

6

It is important, however, to take the precautions recommended by art historian Svetlana Alpers in ‘On the Emblematic Interpretation of Dutch Art’, the appendix of her book The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983, pp. 229–234.

7

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Souvenirs (1755–1842), Paris: Honoré Champion, 2015, pp. 386–387 and 430.

8

Séverine Sofio, Artistes femmes. La parenthèse enchantée (XVIIIe-XIXe siècle), Paris: CNRS Éditions, 2016, pp. 307–309.

9

For Laure Brice, see S. Sofio, Artistes femmes…, op. cit., p. 293. For Sophie Vincent-Calbris, see Camille Belvèze and Alice Fleury (ed.), Où sont les femmes? Enquête sur les artistes femmes du musée, exh. cat. [Lille, Palais des Beaux-Arts, 20 October 2023–11 March 2024], Lille: Invenit, 2023, p. 68.

10

Alexandra K. Wettlaufer, ‘Brontë’s Portraits of Romantic Resistance: The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’, in Portraits of the Artist as a Young Woman: Painting and the Novel in France and Britain, 1800–1860, Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2011, p. 241: ‘Demonstrating woman’s ability to conceive and produce both artworks and children, Helen transcends the classically gendered structures of artistic production and reproduction. [. . .] Brontë has put her in control of her son, her artwork, her now deceased husband’s property (which originally came from Helen’s family anyway), and her erotic life’.

11

In this regard, see ‘Landscape and Politics’ in Malcolm Andrews, Landscape and Western Art, Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 157: Andrews points out that “the degree to which landscape is bound up with issues of property and territorial control, the masculine ‘command’ of a view. Women were credited with an aptitude for sensitive miniaturist portraits of cottages, village scenes, flowers, but were held to lack the intellectual virility to be able to organize a spacious, multifarious landscape.”

Marie Gord is head of research and documentation at the Louvre-Lens. She developed an interest in landscape painting while researching symbolist landscapes in Lombardy during her art history studies. A co-curator of the exhibition Paysage. Fenêtre sur la nature (The Landscape: A Window on Nature) (March–July 2023, Louvre-Lens), she authored an essay titled ‘Peintresses et paysages: l’art de faire tapisserie’ (‘Women Painters and Landscapes: The Art of Making a Tapestry’), examining women’s absence from the history of landscape painting, for the catalogue.

Marie Gord, "Women Artists and the Landscape in the West: Pathways and Obstacles." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/women-artists-and-the-landscape-in-the-west-pathways-and-obstacles/. Accessed 11 February 2026