Olive Rebecca Rush

Gilmore, Jann, Olive Rush: Finding Her Place in the Santa Fe Art Colony, Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 2016

→Guest, Grace, “Olive Rush, Painter,” New Mexico Quarterly, Albuquerque: University of New Mexico, Volume XXI, Winter 1951, no. 4, p. 406-421

→LeVinnes, W. Thetford, “Artists Work in Quiet Amid Survival of Ancient Cultures in Santa Fe Area,” Kansas City Times, May 31, 1949

Olive Rush Paintings, Art Gallery of the Museum of New Mexico, April 1-30, 1957

→Olive Rush, Washington Arts Club, Washington, DC, April 1944

→Exhibition of Paintings by Olive Rush, Allerton Galleries, Chicago, April 21-May 5, 1928

American painter.

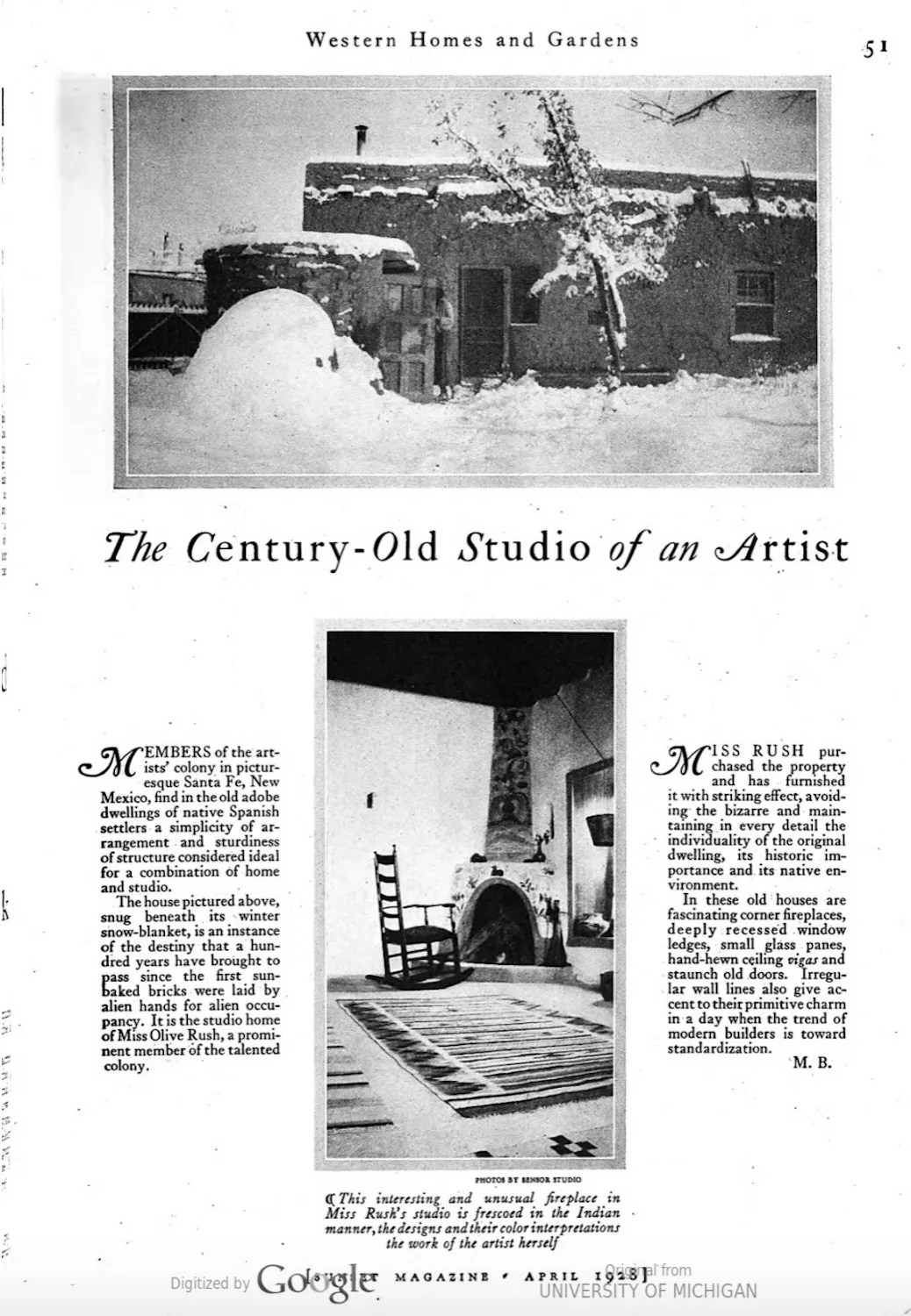

Olive Rush was born a Quaker amongst six siblings, and was the first in her family to attend college. At an early age, she exhibited artistic talent at Fairmount Academy, which was located on her family’s farm. She later enrolled in Earlham College, where she was encouraged to attend professional art school in the Eastern United States, first studying at the Corcoran Museum School in Washington, DC. After visiting the Chicago 1893 World’s Fair’s Women’s Building, she moved to New York City, having been encouraged by women’s advancements in the arts as a profession. She studied at the Art Students League from 1895 until 1899. During this time, O. Rush illustrated for Harper’s Weekly and later for the New York Tribune. While she worked, she lived and shared studios with other women art students and, as was the custom, spent several summers in New England art colonies.

Noted teacher Howard Pyle (1853–1911) accepted O. Rush in his Delaware illustration school in 1904. Camaraderie with other women artists continued as she travelled to Belgium, England and Paris. There she associated with friends at Reid Hall, the American Girls’ Club, located at 4 rue de Chevreuse, which provided women with a haven for “serene creative moments” at mealtimes, teas and special exhibitions. At this Latin Quarter club, O. Rush interacted with fellow artists Ethel Pennewill Brown (1878–1960), Alice Schille (1869–1955), Ethel Mars (1876–1959), Blanche Lazzell (1878–1956) and Anne Goldthwaite (1869–1944).

In 1914 O. Rush visited the American Southwest, where she had the first women’s solo exhibition in New Mexico. She spent the winter in Phoenix and Tucson, Arizona, and painted Indian Children at San Xavier (tohono o’odham Village). Later at the state’s Grand Canyon, O. Rush wrote about her trip into the canyon in bloomers and a divided skirt where the sun shone, birds sang and blooming flowers were “strange to a Hoosier (Indiana) tourist”. Before she reached Santa Fe, she stopped at the Laguna and Acoma pueblos to observe Indian life and painted Portrait of an Indian Family. The Albuquerque, NM newspaper wrote of “her genius as a painter” making her “one of the best women painters in the United States” (“Santa Fe Society Notes: Art is Long”, Albuquerque Morning Journal, May 24, 1914).

O. Rush became a nationally-known easel painter and New Deal true fresco muralist under the 1930s Federal New Deal programmes. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) employed creatives including artists to create art depicting the role of the common man and familiar American places – what is today termed the Regionalism Movement. O. Rush painted true fresco murals at the Santa Fe Public Library in 1934, and in 1936 adorned the ceiling entrance of the Biology Building at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces, with a theme of cotton and chili farming. Rush also painted two US Post Office Building murals (on canvas) for the Post Office in Pawhuska, Oklahoma in 1938 and the Florence, Colorado Post Office in 1939. Each mural depicted scenes indigenous to these locations.

O. Rush was amongst the first to teach Native American art students to interpret their own culture at the Santa Fe Indian School. O. Rush pushed for their native works to be shown at the 1932 Chicago Century of Progress Exposition the next year. Several of these pueblo students later became successful artists, including Santa Clara’s Pablita Velarde (1918–2006). O. Rush co-founded the Friends Meeting in her home and bequeathed it to the Quakers. As an early environmentalist, she objected to paving roads in her historic neighbourhood, promoted open spaces and hosted community events in her popular garden.