Itsuko Hasegawa

Itsuko Hasegawa, Kozo Kadowaki, et.al., Dialogue− Itsuko Hasegawa, Hiroshi Hara, and Toyo Ito in the Age of Crisis, Tokyo, Montreal: Millgraph and CCA, 2025

→Itsuko Hasegawa, Hasegawa Itsuko no Shikou, Tokyo: Sayusha, 2019

→Itsuko Hasegawa, ITSUKO HASEGAWA, Tokyo: Kajima Publishing, 2015

Landscape Architecture, Künstlerhaus, Salzburg, August 2009

→Itsuko Hasegawa: Réalisations et projets récents (Recent Buildings and Projects), l’Institut français d’architecture (IFA), Paris, March 20-May 31, 1997; “Fluctuations,” Aedes Galerie East, Berlin, July 11-August 14, 1997; Norsk Form, Oslo, 1997; Nederland Architectuur Instituut (NAi), Rotterdam, 1998

→Architecture as Second Nature: Hanging Garden, Gallery MA, Tokyo, March 27-April 26, 1989

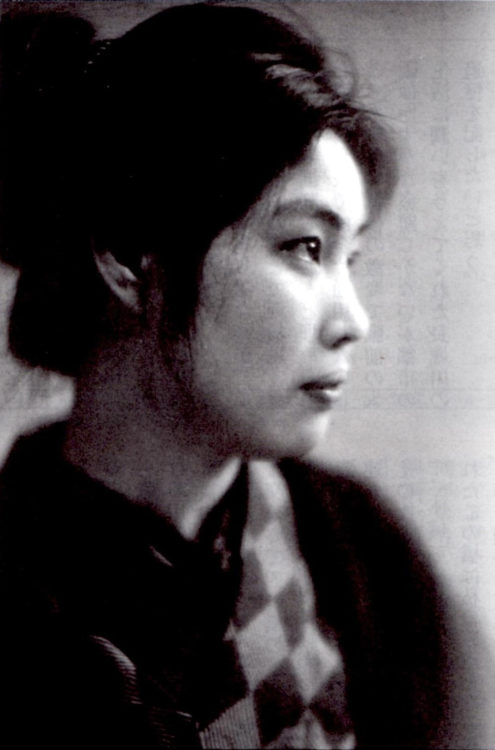

Japanese architect.

Hasegawa Itsuko is not only an innovative architectural designer but also a pioneer in redefining the traditional role of the profession. She has worked to enrich architecture by listening to the diverse voices of residents and users, seeking to integrate architecture more deeply into society.

Hasegawa was born in 1941 in the port city of Yaizu. She was a curious and multi-talented child. During her days at a girls’ school, she collected mountain plants, sailed yachts and wrote and directed plays. Although she aspired to pursue a career in architecture, she faced gender-based obstacles that nearly derailed her ambition. However, the architectural models she created at the local university, where she had enrolled only reluctantly, opened up a door to her future. The models caught the eye of renowned architect Kiyonori Kikutake (1928–2011), who recognised her talent.

Hasegawa’s career is notable for her rare experience working with Japan’s two leading architects at the time: first with Kikutake for over ten years starting in the mid-1960s, and later with Kazuo Shinohara (1925–2006), whose architectural philosophy sharply contrasted with Kikutake’s. This experience may have shaped her distinctive mission to liberate architecture and its users from authoritarian control. The early residential projects she undertook in her own right during her time at the Shinohara Laboratory, such as House in Yaizu 1 (1972) and House in Midorigaoka (1975), are characterised by a minimalist aesthetic, which reflects Shinohara’s influence. At the same time, her emphasis on open, flexible spaces that foster interaction amongst residents and a close relationship with nature led to increasing demand for residential designs.

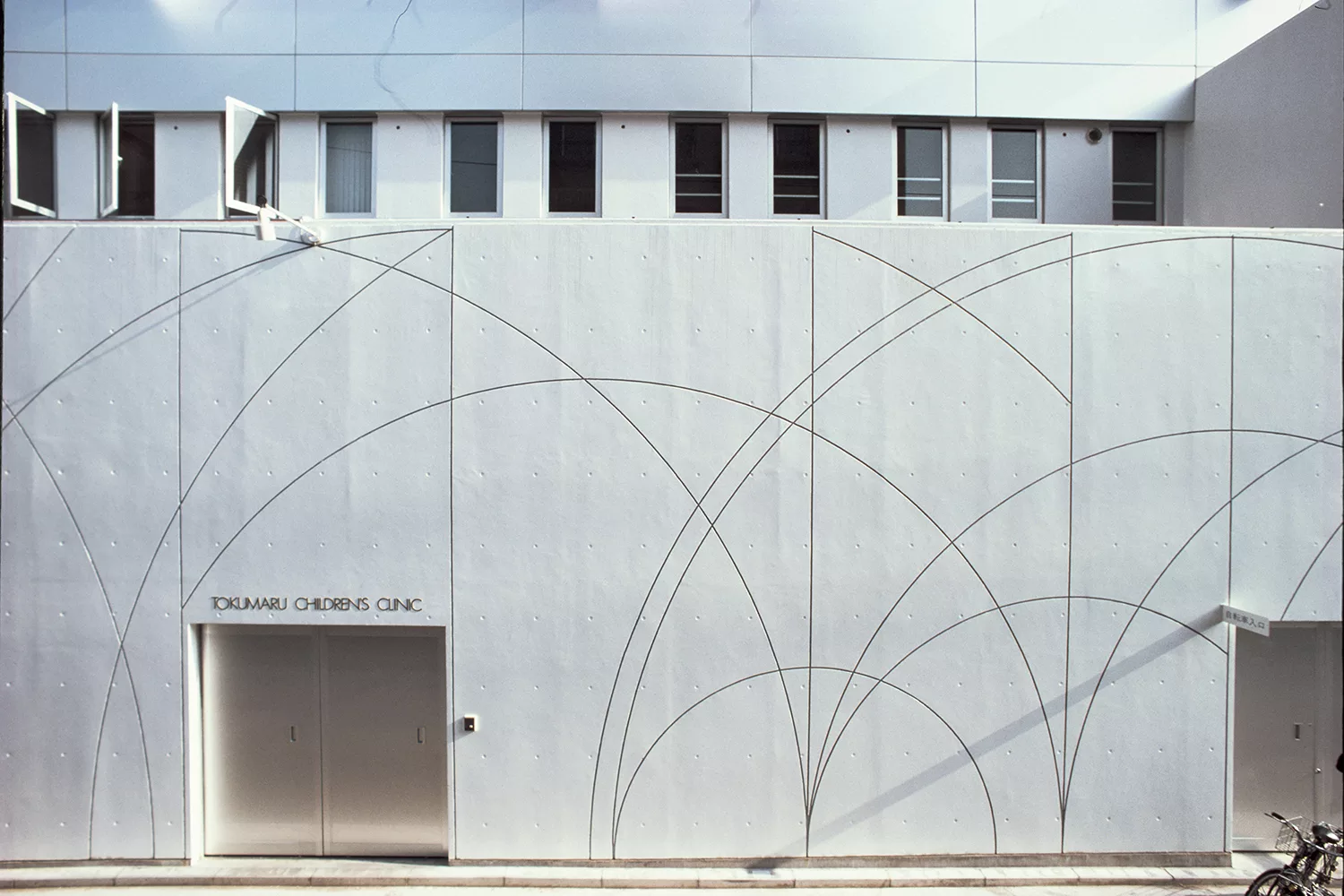

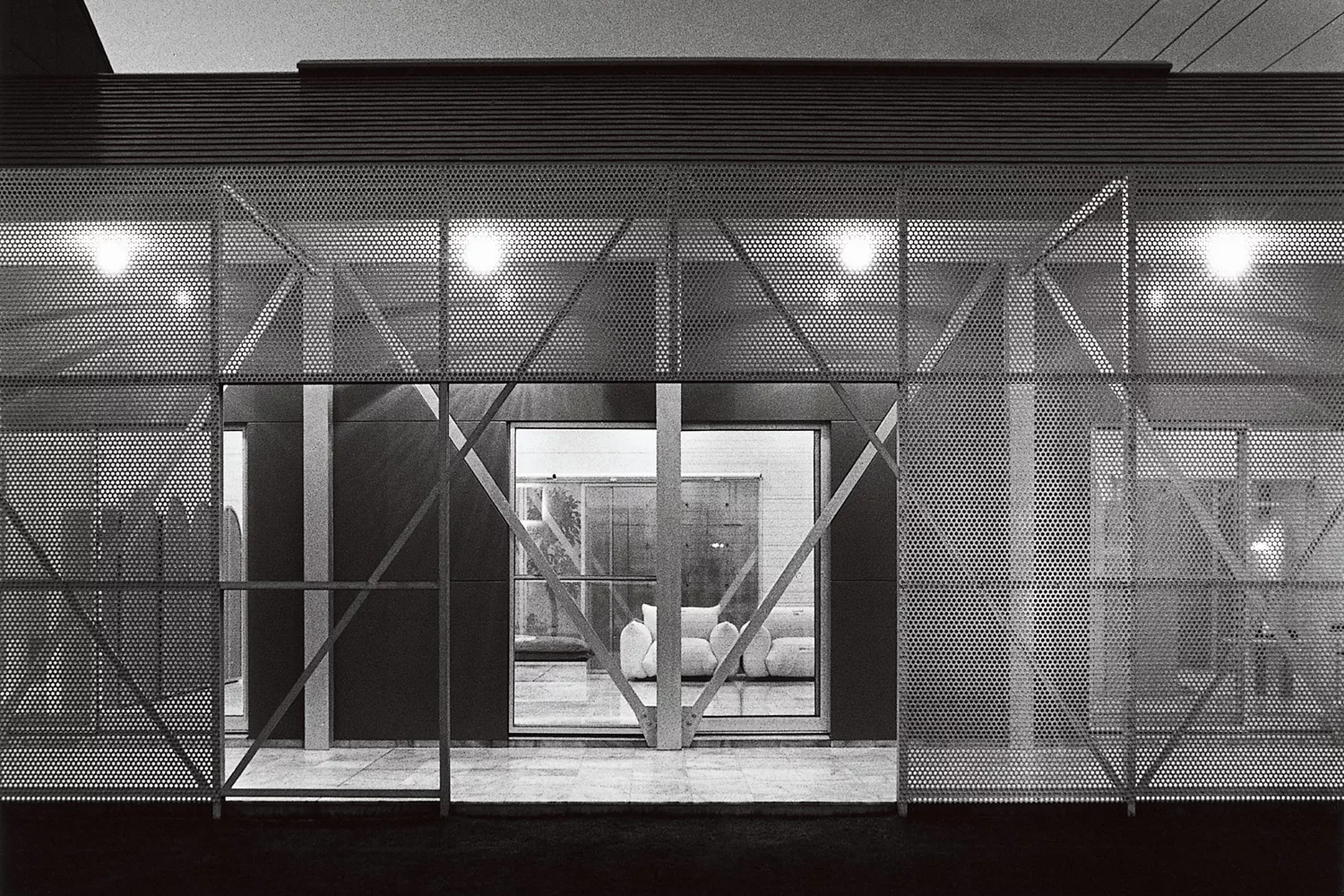

After establishing her own practice in 1979, Hasegawa gained wide attention with her design for the Kuwahara House (1980), where she pioneered the use of perforated metal sheeting on the exterior. This lightweight material allowed faint glimpses of the outside world, strongly resonating with the spirit of the time. Hasegawa’s subsequent project, Bizan Hall (1984), a training facility, featured open, adaptable spaces and a modest scale to harmonise with the surrounding residential neighbourhood. At a time when architecture was typically conceived as self-contained entities, her approach of integrating architecture into the urban context was groundbreaking. For this, Hasegawa received the highly prestigious Architectural Institute of Japan’s Prize for Design. Hasegawa became an undisputed figure in the field of design for the Shonandai Cultural Center (1990), which marked the first time a woman architect won a public architecture competition in Japan. Most of the cultural facility’s functions were placed underground, while the undulating terrain was covered with large and small spheres, house-like structures, forests, walkways and streams. Arranged like an archipelago, the complex formed a natural setting where people could gather, learn, and enjoy themselves – revealing new possibilities for cultural facilities. Hasegawa actively engaged in dialogue with local residents, which demonstrated the value of public participation, significantly influencing Japan’s approach to public architecture. Hasegawa continued to design a number of major public cultural and educational facilities, including the Sumida Culture Factory (1994), Yamanashi Fruit Museum (1995) and Niigata Performing Arts Center (1998). In each case, she expanded the possibilities of architecture through repeated dialogue with users. She also conducted interviews and workshops on programmatic and operational aspects, offering proposals that went beyond the conventional role of the architect. Though her efforts to transcend traditional boundaries often met with resistance, she remained committed to addressing the disconnect between architecture and programme planning, which continues to persist worldwide.

Hasegawa views public architecture as a harappa, or open field. Cultural facilities, in her view, should not be monumental structures but rather accessible and welcoming spaces – like a harappa – where diverse people can interact freely. She strives to create architecture that becomes a ‘second nature’, like satoyama – the cultivated natural zones between village and mountain. Throughout the 2000s and 2010s, Hasegawa continued to design large-scale institutions such as Shizuoka Taisei Junior and Senior High School (2004) and Suzu Performing Arts Center (2006), as well as numerous housing complexes and private residences. More recently, her focus has turned to education and cultural enrichment in architecture. In 2016 she established Gallery IHA in central Tokyo, followed in 2017 by the non-profit organisation ‘Kenchiku-to-art-no-dojo’ (Training Hall for Architecture and Art), creating a platform for dialogue and exhibitions for young architects and students. In 2018 Hasegawa received the Royal Academy Architecture Prize from the Royal Academy of Arts in the UK.