Renée Gailhoustet

Bénédicte Chaljub, Renée Gailhoustet, Une poétique du logement, ed. Monum, coll. Les carnets d’architectes, 2019

→Bénédicte Chaljub, La politesse des maisons, Renée Gailhoustet, architecte, ed. Actes Sud, coll. L’Impensé, 2009, 85 p.

French architect.

Renée Gailhoustet’s extraordinary oeuvre has something to teach us about the role women have held in the history of architecture. Although she never spoke about feminist practices in the profession or considered her work on housing to be a female area of focus, she worked in a highly gendered profession. In 1962, when she began her career, only one percent of women architects ran their own business.

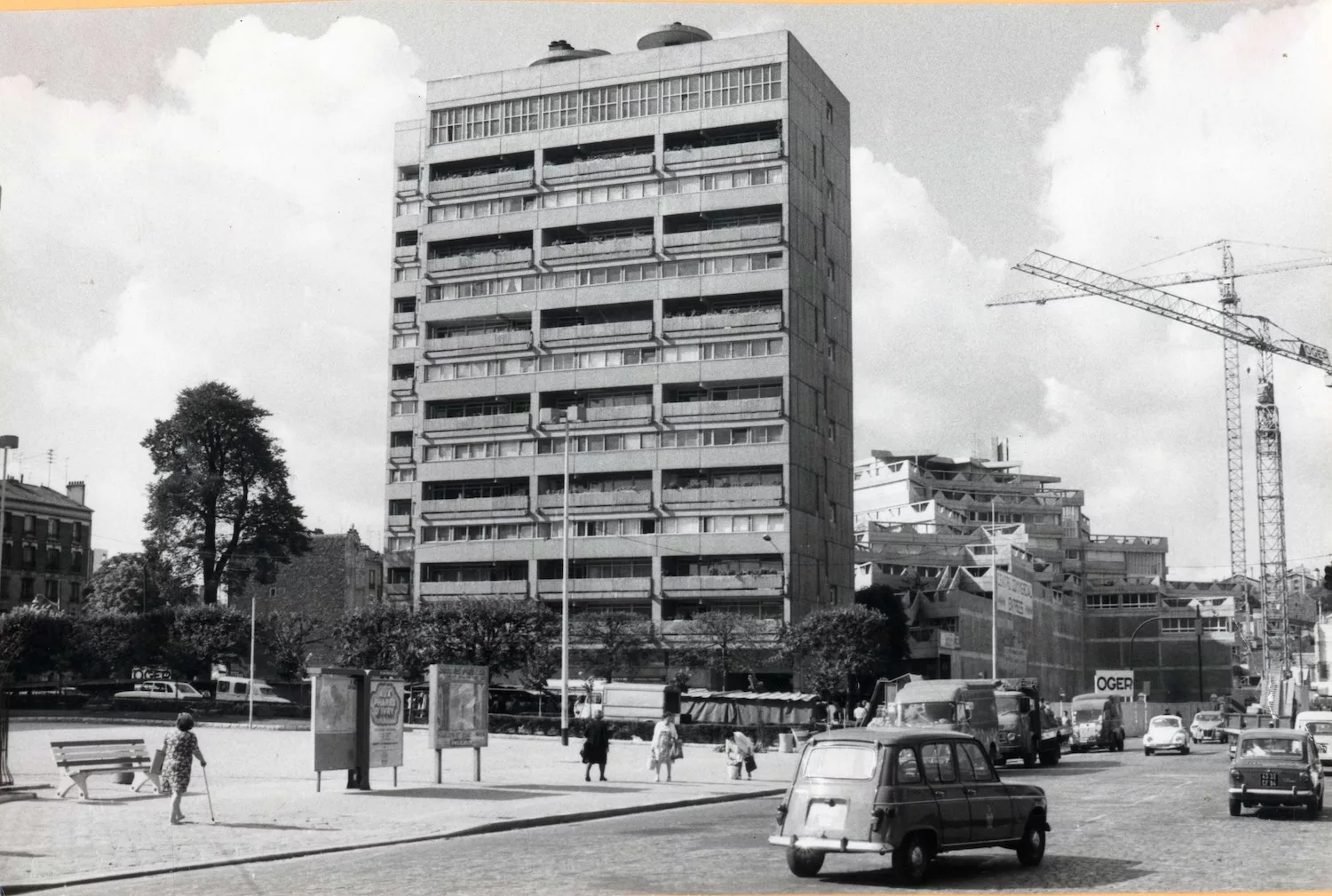

In the previous year, she had completed her studies at the École des Beaux-Arts de Paris, where she was active in the Communist party. Upon graduating, she joined a firm run by Roland Dubrulle (1907–1983), who shared her political views. Soon after taking this position, she received her first project: an eighteen-storey social housing tower (La Raspail, 1968) for the city of Ivry-sur-Seine in the Val-de-Marne department just outside Paris. At around the same time, she began work on Ivry-sur-Seine’s urban renewal project. In her social housing design, she turned away from contemporary models for large complexes, criticising their scale and repetitive “cell” structure. She opted instead for brightly lit spaces, innovative layouts, staggered levels and open-plan concepts that embraced modernity.

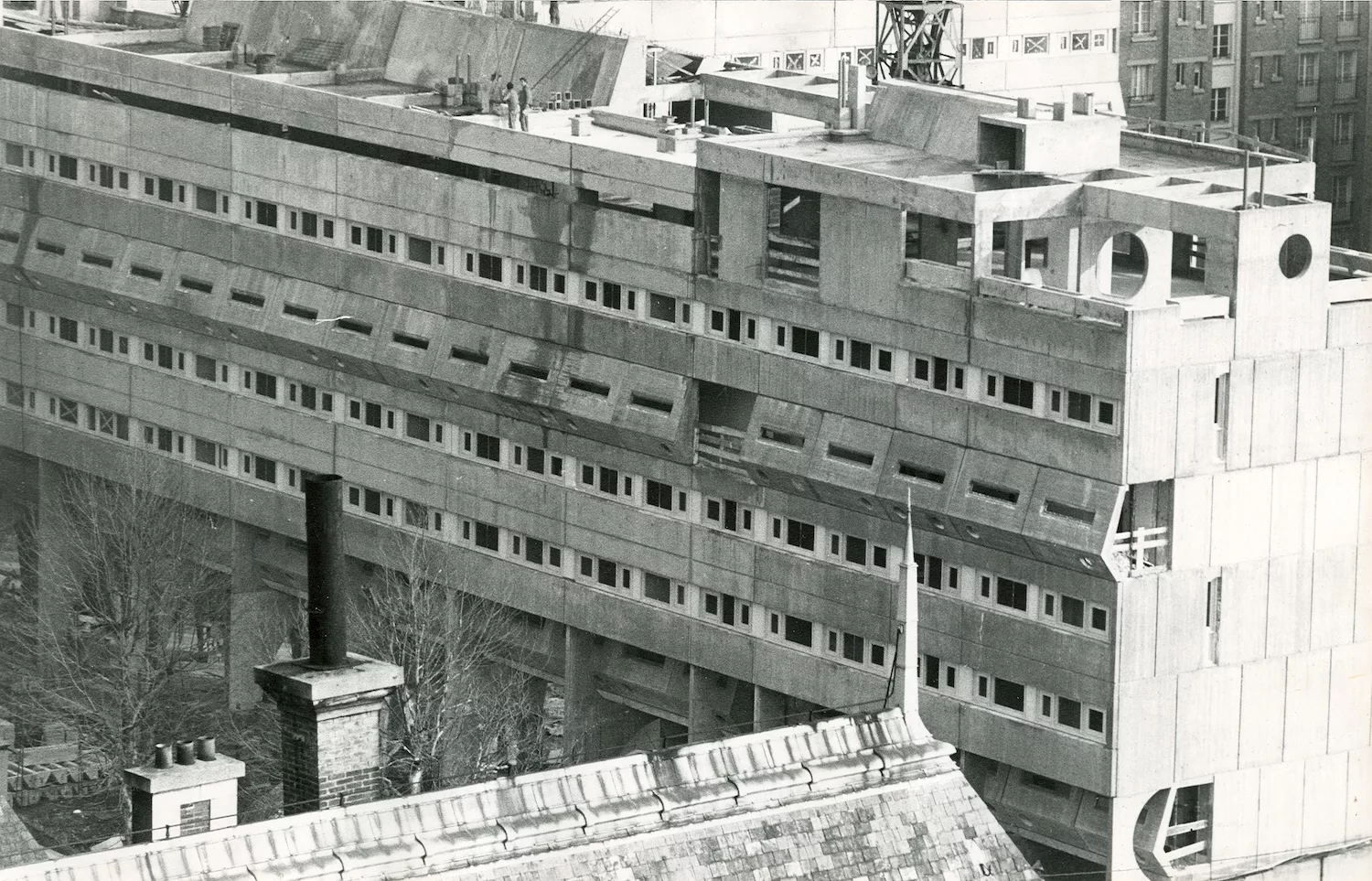

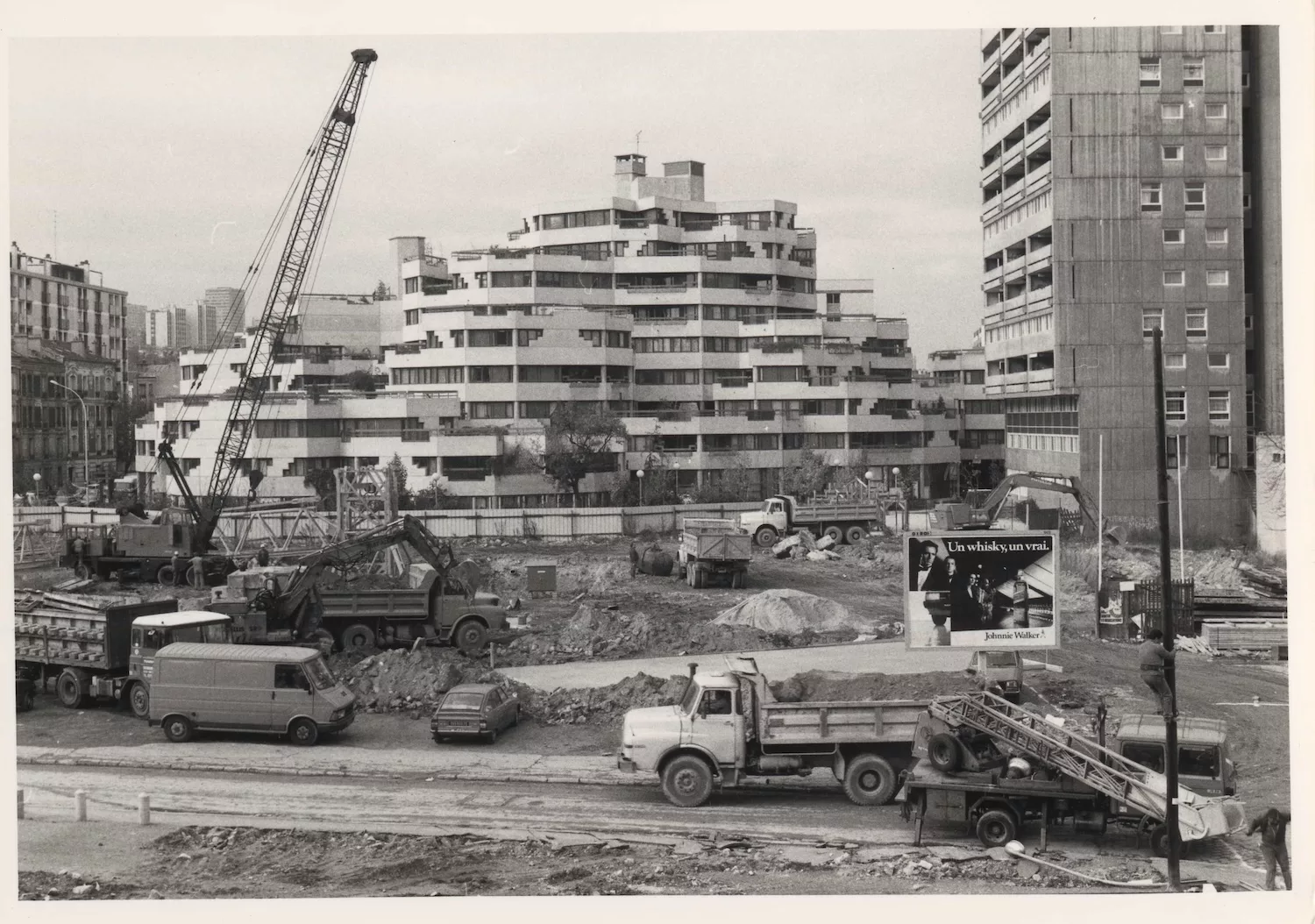

But her groundbreaking béton brut architectural designs for working-class suburban residents required the right production conditions to see the light of day. Her project partners followed her lead, prioritising generous spatial layouts over inner amenities and tirelessly seeking grants. The scope of the Ivry-sur-Seine urban renewal project coordinated by France’s low-income housing office – 2000 units and associated facilities – prompted her to bring a second chief architect on board. She chose Jean Renaudie (1925–1981). The favourable context they enjoyed included a certain permissiveness in the wake of the May 1968 student revolt. This gave J. Renaudie free rein to dream up triangular and pyramid-shaped buildings with terrace gardens, marking a sharp break from customary conventions. R. Gailhoustet drew inspiration from his contribution. Her first towers (Raspail, Lénine, Casanova and Jeanne Hachette, constructed between 1968 and 1975) and her Spinoza housing unit (1972) were followed by complexes with innovative geometrical forms and planted terraces in Ivry-sur-Seine (Le Liégat, 1982; Le Marat, 1986), Aubervilliers (La Maladrerie, 1985) with the firm Sodédat, and Saint-Denis (Îlot 8 de la ZAC Basilique, 1985). She continued to design similar structures in Villejuif (1985) and on France’s Reunion Island (Le Port, La Possession, 1989).

In the mid-1980s, shifts in attitudes and urban planning regulations, coupled with smaller project scales, forced R. Gailhoustet to return to standard building conventions and brick or stucco cladding in Gentilly, Villetaneuse and Romainville (1994–1996), but she continued to pursue architectural and spatial innovations and maintained her exacting standards in terms of housing quality. She also designed a middle school in Montfermeil (1993). The many buildings she designed over her career are enjoyable to live in and encourage a sense of appropriation.

Though J. Renaudie won France’s Grand Prix National de l’Architecture in 1981, R. Gailhoustet’s contribution would not be recognised for another forty years. In 2018, she received the Médaille d’Honneur from France’s Académie d’Architecture, followed by the Berlin Grand Art Prize (2019), the Architecture Prize from the Royal Academy of Arts in London and the Grand Prix d’Honneur from the French Ministry of Culture (2022). La Maladrerie and Le Liégat were both given the Architecture Contemporain Remarquable label (in 2008 and 2022) and La Raspail was listed as a historical monument (2021).

Le quartier de la Maladrerie – Aubervilliers | Conseil départemental de la Seine-Saint-Denis, September 2023 (French)

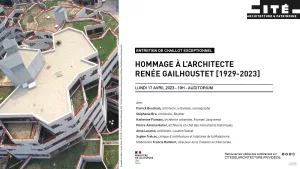

Le quartier de la Maladrerie – Aubervilliers | Conseil départemental de la Seine-Saint-Denis, September 2023 (French)  Hommage à l’architecte Renée Gailhoustet [1929-2023] | Citée de l’Architecture, May 2023 (French)

Hommage à l’architecte Renée Gailhoustet [1929-2023] | Citée de l’Architecture, May 2023 (French)  Renée GAILHOUSTET, Architecte. Journée d’étude, 31 mars 2015 | ENSAD Limoges, March 2015 (French)

Renée GAILHOUSTET, Architecte. Journée d’étude, 31 mars 2015 | ENSAD Limoges, March 2015 (French)