Agnès Varda

Perceval Sophie (ed.), Agnès Varda : l’île et elle. Regards sur l’exposition, exh. cat., Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, Paris, (18 June – 8 October 2006), Paris/Arles, Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain/Actes sud, 2006

→Chéroux Clément & Ziębińska-Lewandowska, Karolina (eds.), Varda-Cuba, exh. cat., Musée National d’Art Moderne – Centre Georges-Pompidou (11 November 2015 – 1 February 2016), Paris, Éditions du Centre National d’Art et de Culture Georges-Pompidou, 2015

Agnès Varda, Galerie Municipale du Château d’Eau, Toulouse, November 1987

→Agnès Varda, y a pas que la mer : exposition, Musée Paul-Valéry, Sète, 3 December 2011 – 22 April 2012

French film-maker, photographer and visual artist.

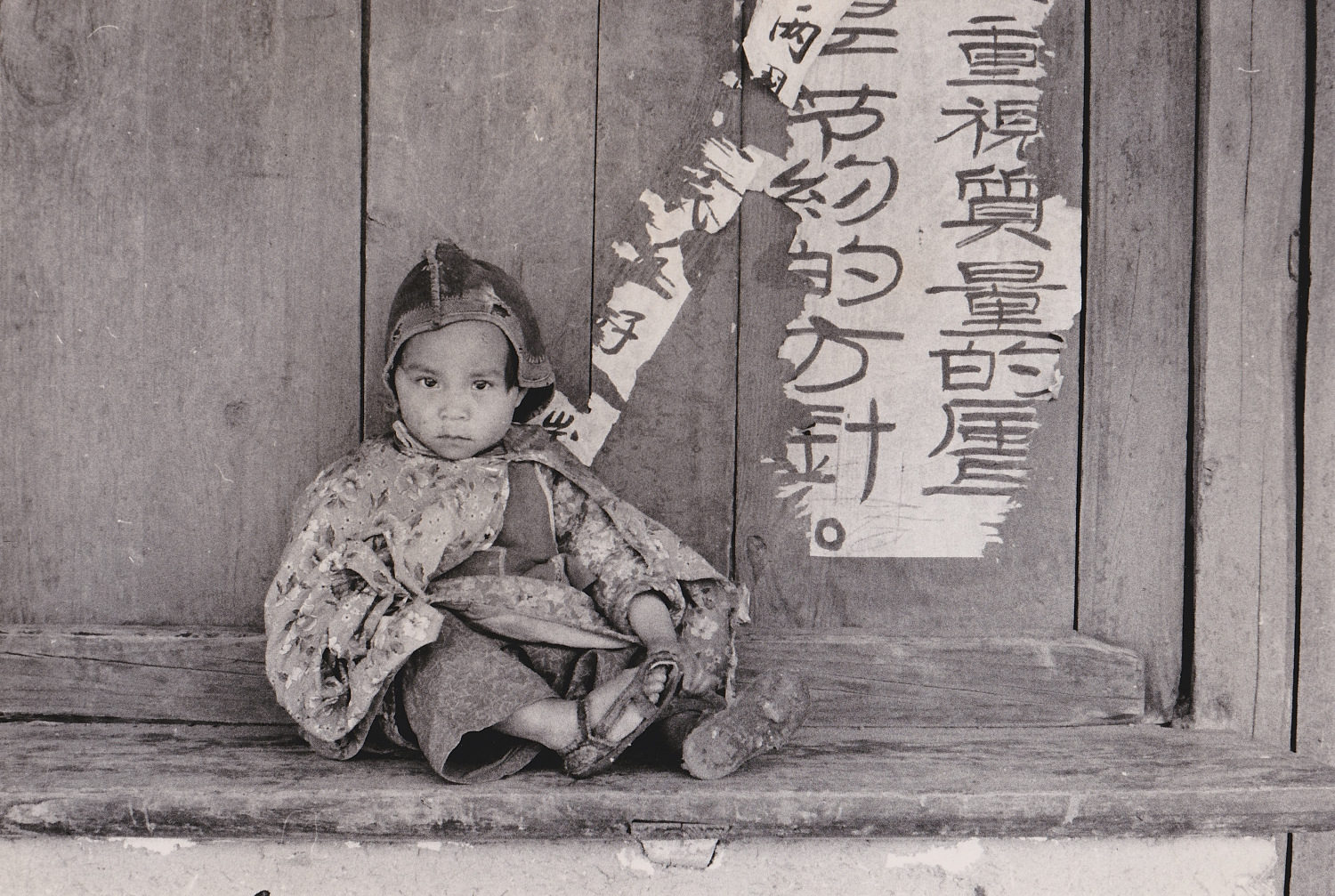

After living in Belgium and then in Sète (southern France), Agnès Varda studied photography in Paris at the École de Vaugirard, and became a photographer at Jean Vilar’s National Popular Theatre from 1951 to 1961. Without any technical knowledge, and without even being a film enthusiast, she made her first film in 1954, La Pointe courte, wich portrayed the story of the demise of a relationship, into which were interspersed depictions of a fishing neighbourhood in Sète. Alain Resnais provided the editing for the project. A successful first attempt; the film was acclaimed by critics as a breath of fresh air, and won the Grand Prix for avant-garde film in Paris. This earned its director the nickname “the grandmother of the New Wave”, which she rejected because she did not feel part of any collective. She soon created her own production company, Ciné-Tamaris, which enabled her to establish herself as a “craftswoman” and to pursue her creative work in complete freedom. While she continued working with short films – a medium she was particularly fond of because it permitted creative impulses to take form more quickly – she also produced feature films, an art form she viewed as yet another zone of experimentation. She seized every opportunity she could: a commission about the châteaux of the Loire (Ô saisons, ô châteaux, 1957), another on the Riviera (Du côté de la Côté, 1958), a work based on photographs taken during a trip to Cuba (Salut les Cubains, 1963), and a film about an uncle rediscovered by chance in San Francisco (Oncle Yanco, 1967). In these works, she displays a gift for turning everything into film and juggling with formats, genres, and conventions – making reality and fiction merge through the elegance of a playful subjectivity, a unique way of looking at things, one that is both mischievous and generous. Always curious about the other, she celebrates the encounter in all its forms within her “subjective documents” (to use her own words), such as L’Opéra-Mouffe (1958, a notebook documenting a pregnancy in the Mouffetard neighbourhood); Daguerréotypes (1975, “filmography of [her] neighbours”, selected for the Best Documentary Oscar); and Cléo de 5 à 7 (1961 Méliès Prize), a feature film about a singer awaiting the results of a medical analysis and wandering around Paris in a state of both poetry and anxiety. In this film especially, her form was innovative (we follow Cléo’s day and thoughts in real time), and her themes were courageous (death, taboos surrounding cancer, the Algerian war); it became a cult classic. After Le Bonheur, another daring film awarded many prizes (1964, Delluc Prize, Silver Bear at Berlin), Varda followed her companion, Jacques Demy (they met in 1958), to Los Angeles, where she hung out with Warhol and his gang. While there, she made two films bearing witness to the period (Black Panthers, 1968; Lions Love, 1969).

In the years that followed, two films she directed, Réponses de femmes (1975), and L’une chante l’autre pas (1976), marked a high point in the struggle for women’s rights, treating their serious topic with lively wit. The works of A. Varda are tied up with and shed light on the eras in which they were made, while her own artistic activity has evolved in tandem with technical and social changes. In 1985, she was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice film Festival for Sans toi ni loi, a reconstruction of the tragic last days of a young vagabond (Sandrine Bonnaire) using the testimony of people who crossed paths with her; one her greatest achievements, this film remains her greatest commercial success. After two closely related films with/about Jane Birkin* (one titled Jane B. par Agnès V., 1987) and three others in homage to Demy (including one titled Jacquot de Nantes, 1991), her career took a new turn in1999. She welcomed new technologies in photography, and saw in her small digital camera new ways of remaining close to her subjects, she directed a highly personal work which touched a large number of viewers: Les Glaneurs et la Glaneuse (2000). Exploring social themes, in line with her documentary method of investigation and her liking for narratives marked by abrupt shifts, she sought out people struggling against precariousness with wit and ingenuity. In 2008, she made Les Plages d’Agnès, a self-portrait that reflected on her work and her life, and for which she was awarded the César for best documentary film. More recently, she has also created installations, including L’Ile et Elle, which was shown by the Cartier Foundation for Contemporary Art in 2006 and Les Cabanes d’Agnès, which was exhibited in 2009 at the Lyon Biennale of Contemporary Art. She has received a host of prizes and distinctions from around the world, including the René-Clair Prize from the French Academy, which rewarded the whole of her œuvre in 2002, and the Carrosse d’Or (awarded by the Society of Film Directors) at the 2010 Cannes Festival; among her most prestigious awards is the Palme d’honneur of the Cannes Festival, which she was the first woman to receive, in 2015.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2018

L'île et elle: Agnès Varda at Fondation Cartier

L'île et elle: Agnès Varda at Fondation Cartier