Amrita Sher-Gil

Singh Iqbal, Amrita Sher-Gil, New-Delhi, Vikas, 1984

→Sundaram Vivan, Amrita Sher-Gil: A Self Portrait in Letters and Writings, New-Delhi, Tulika, 2010

→Dalmia Yashodhara, Amrita Sher-Gil : art & life : a reader, New Delhi, Oxford University Press, 2014

Amrita Sher-Gil, Ernst Museum, Budapest, 5 September – 3 October 2001

→Amrita Sher-Gil, Tate modern, London, 28 February – 22 April 2007

→Remembering Amrita Sher-Gil: From the Repository of National Gallery of Modern Art, National Gallery of modern art, New-Delhi, 2015

Indian painter.

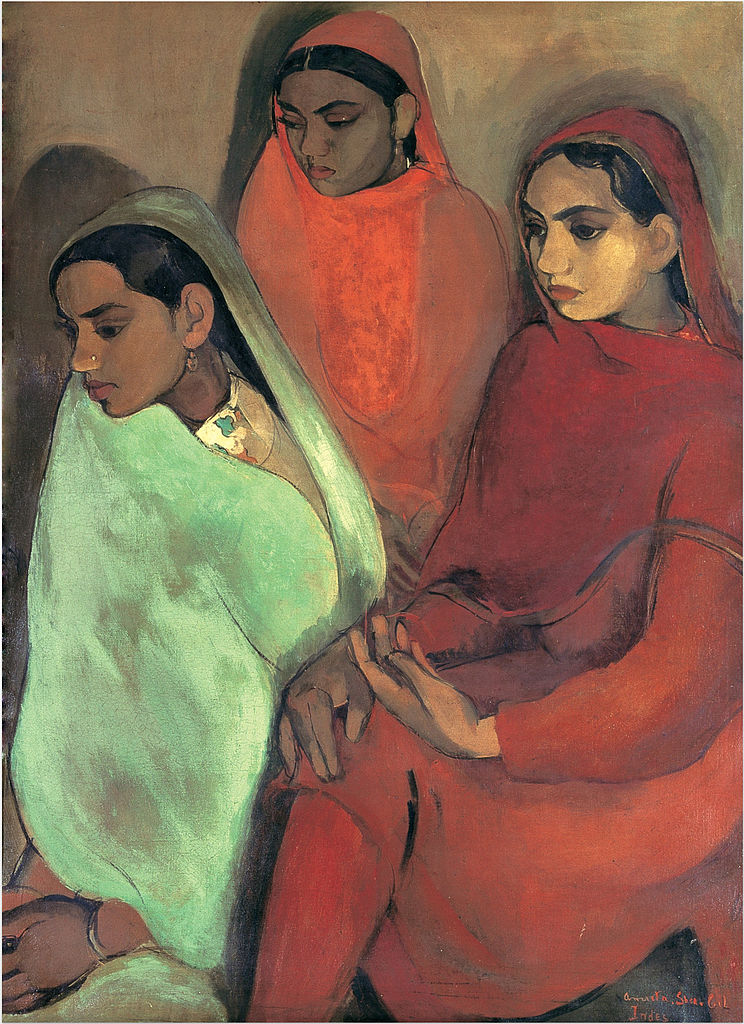

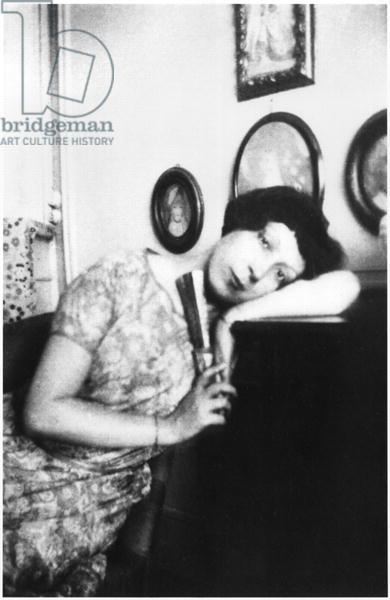

The daughter of a Sikh aristocrat and a mother that came from the Hungarian bourgeoisie, Amrita Sher-Gil was born in Hungary, where her family lived during World War I, before moving back to Simla, in the north of India, in 1919. She was introduced to visual arts and music from a very young age, and showed a predisposition for drawing. The family moved to Paris in 1929 so that she could follow the classes of Pierre Vaillant at the Grande Chaumière Academy, and attend Lucien Simon’s workshop as a “free student” at the School of Fine Arts until 1934. She made mostly life portraits during these Parisian years, and concentrated on studio and outdoor painting in a style similar to Post-Impressionism and classical interwar Realism. In 1934 her Parisian works became more introspective and her style increasingly pared down. Conscious of the limits of her art, she questioned her identity and decided to go back to India. At first, her romantic imagination prompted clichés depictions of India: tearful mothers in Mother India (National Gallery of Modern Art [NGMA], New Delhi, 1935) or sombre portraits of anonymous villagers. However, she sought to transform her style by confronting it with the country’s classical artistic tradition.

Her palette brightened and her compositions became more fluid. The most accomplished work of her Southern Indian trilogy is Brahmachari (NGMA, New Delhi, 1937), which shows a group of renouncers. She returned to Hungary to marry her doctor cousin and, when she went back to India, finished Two Girls (NGMA, New Delhi, 1939), which displays the full extent of her mastery of various pictorial influences and shows her “East-West Dilemma” (as quoted by K.G. Subramanyan). Her return to Hungary was marked by a gradual simplification of forms. She broke the conventions of miniatures, altered the traditional and customary image of women, and exalted colour in her portraits of confined women, caught between ennui and desire, as in Woman Resting on Charpoy (NGMA, New Delhi, 1940). After her sudden death at the age of 28, a hundred or so of her works were donated to the Indian government as a “gift to the Nation”; they are exhibited prominently at the NGMA in New Delhi, which was inaugurated in 1954. An edition of Marg magazine was devoted to her in 1972, placing her work at the heart of 1970s issues, mainly relating to identity, granting her the status of national, if not international, artist.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Vivan Sundaram about Amrita Sher-Gil

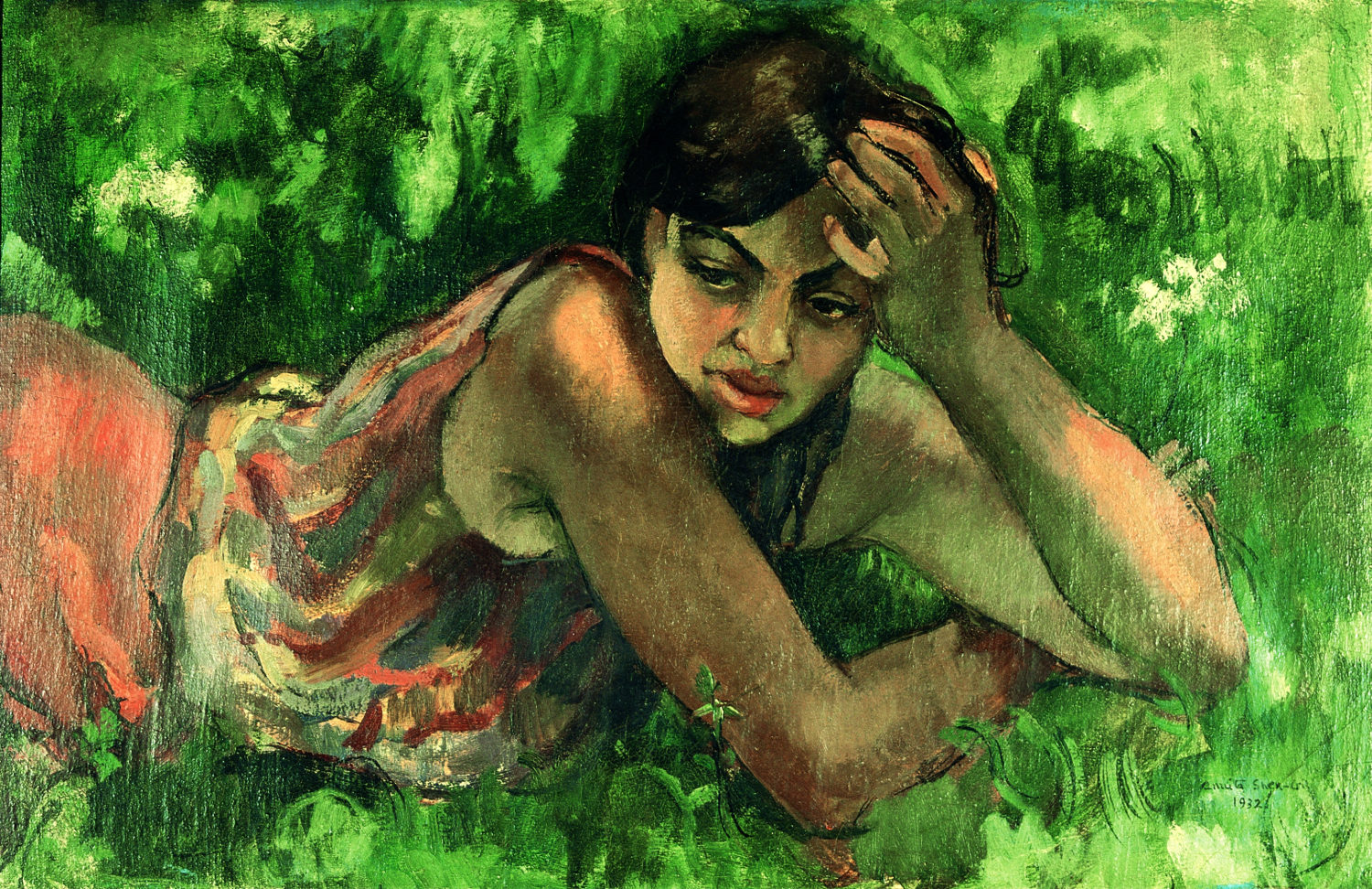

Vivan Sundaram about Amrita Sher-Gil  Amrita Sher-Gil's nephew speaks about her work Untitled [In the garden]

Amrita Sher-Gil's nephew speaks about her work Untitled [In the garden]