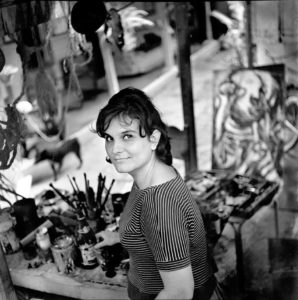

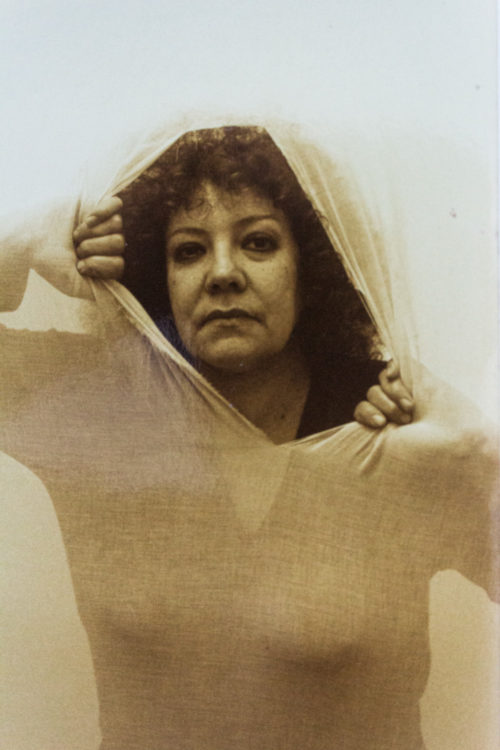

Antonia Eiriz

Antonia Eiriz: Ensamblajes, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Havana, 1964

→Antonia Eiriz: Tributo a una legenda, Museum of Art, Fort Lauderdale, 1995

Cuban painter.

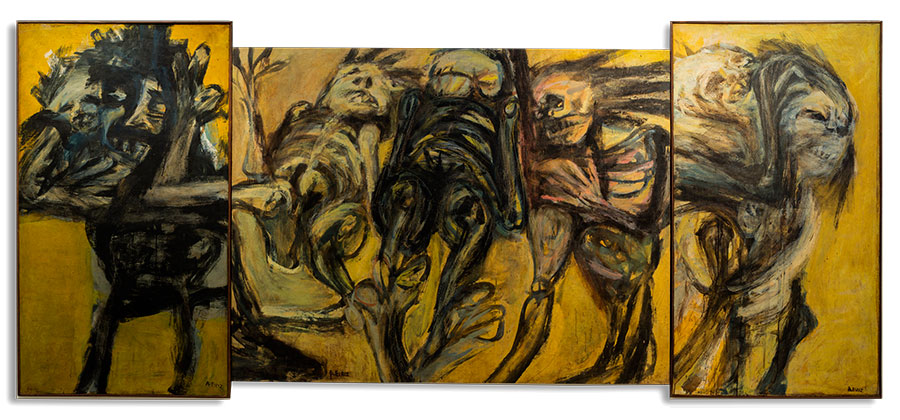

Antonia Eiriz studied at the San Alejandro Academy of Fine Arts in Havana, from which she graduated in 1957. In 1954, in defiance of the institution’s academism, she enrolled in the Grupo de los once [The Eleven], whose members rejected “cubanity” and the picturesque style of the first modernists, in favour of a more abstract language with expressionist overtones. In 1959, the Cuban art world welcomed Fidel Castro’s revolution with hope, initiating a short period of free and intense cultural activity. The painter produced most of her work during the 60s, giving up its abstract aspect while maintaining an expressionist approach. As a central figure of Cuban New Figuration, she was invited to the São Paulo Biennale in 1961. The monstrous figures that populate her large paintings and drawings – particularly the ones she made for the critical review Lunes – convey a tragic vision of humanity, a reflection of her increasing disappointment in the new regime. Her most famous work is an Annunciation (1963), in which a woman sitting at her sewing machine recoils in terror upon seeing an apparition – none other than the angel of death.

When Cuba entered the Soviet orbit in the late 60s, artists became subjected to the propaganda of Socialist realism. In protest, A. Eiriz abruptly stopped painting in 1968. However, she continued to teach in several official institutions, deeply influencing the next generations of artists. The deterioration of living conditions in Cuba after the dissolution of the Soviet Union led her to a state of deep depression. She was authorised to leave the country with her husband in 1993 thanks to a medical prescription. She began painting again as soon as she arrived in Miami: 25 large-scale canvases – one for each year of silence – painted from 1993 to her death in 1995 as a continuation of her tragic vision. Vereda tropical [Tropical Path, 1995] is a violent denunciation of the reactionary dogmatism of her fellow exiles in Miami; its title is borrowed from a popular song that is an inherent part of the nostalgic fantasy that underlies their militancy. But while the song evokes an idyllic walk along a lush path, the painting shows a path leading to a horizon where the light of a dying sun shines over a field of severed heads.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2019