Concha Jerez

Murría, Alicia, Concha Jerez. Interferencias, Las Palmas, Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno, 2017

→Castro Flórez, Fernando, Concha Jerez: Tiempo Dia-Rio, Murcia, CENDEAC, 2016

→Jerez, Concha, Maderuelo, Javier, Picazo, Glòria, Worwag, Barbara, In Quotidianitatis Memoriam, Kassel, Hall K18, 1987

Que nos roban la Memoria, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, July 2020-January 2021

→Concha Jerez: Interferencias, Centro Atlántico de Arte Moderno (CAAM), Las Palmas, October 2017-January 2018

→Concha Jerez: Interferencias en los medios, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Castilla y León (MUSAC), León, July 2014-January 2015

Spanish Conceptual artist.

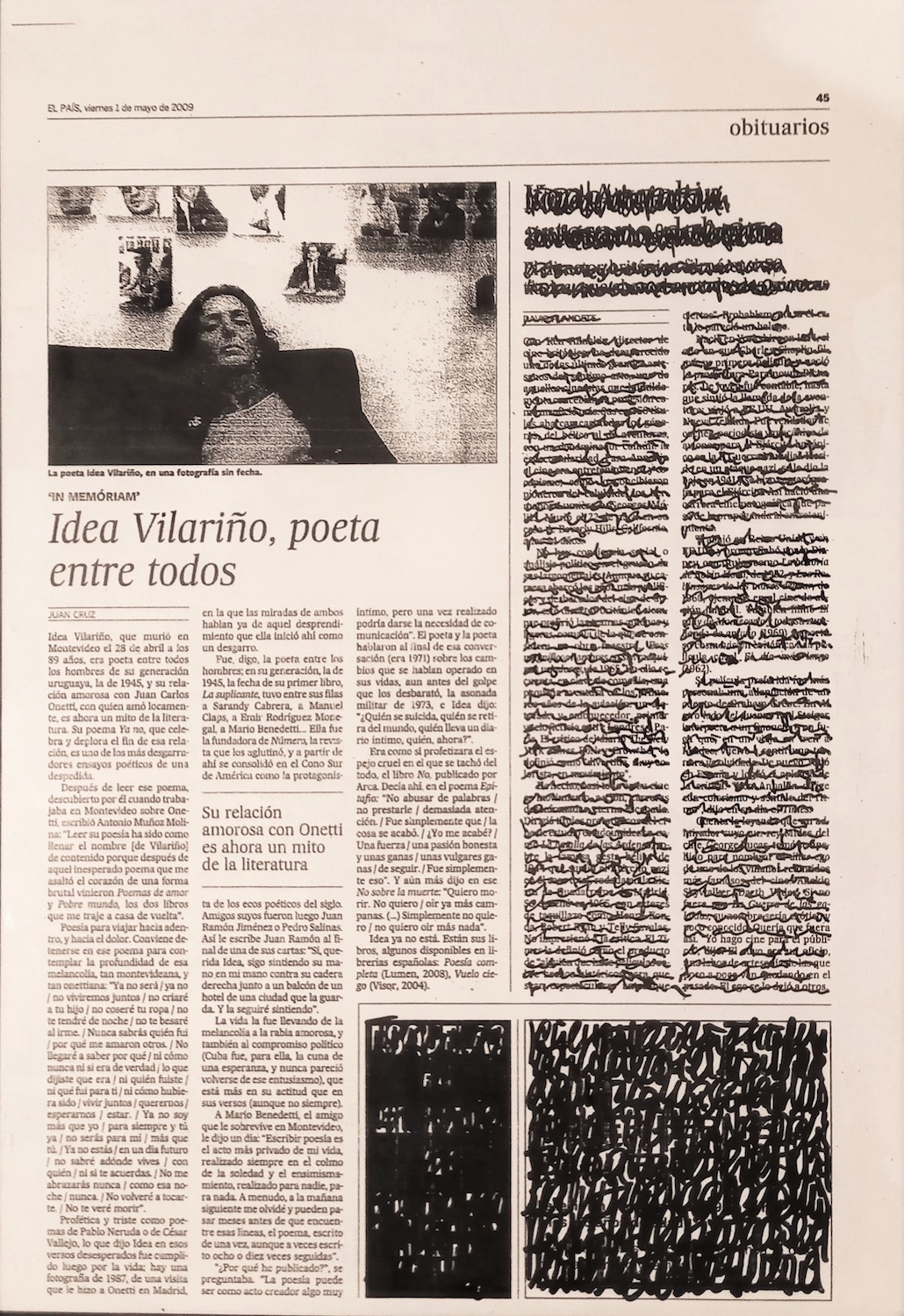

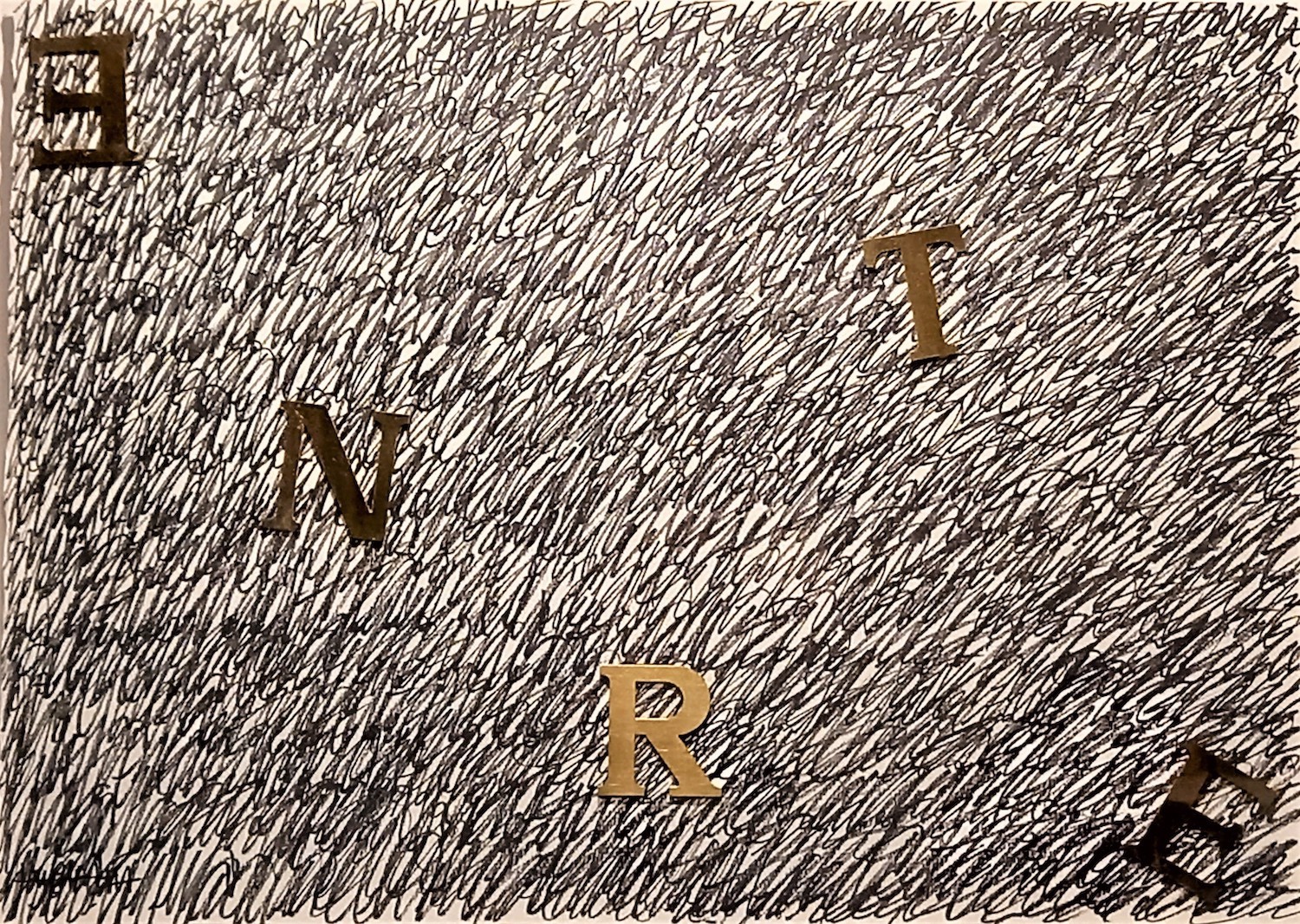

Concha Jerez is one of the pioneers of Conceptual art in Spain. Her highly politicised work considers issues such as repression, censorship and historical memory, deeply rooted in the Spanish context and marked by the long dictatorship and the democratic transition. C. Jerez embraces interdisciplinarity, seeing styles and media as a toolbox. She also views her own work as “interferences” because they seek to put viewers under stress and make them aware of certain realities. As she puts it, her works have an “ideological character that logically arises from today’s reality of a world where injustice, war and destruction prevail. A world in which, in my opinion, artists should interfere.”

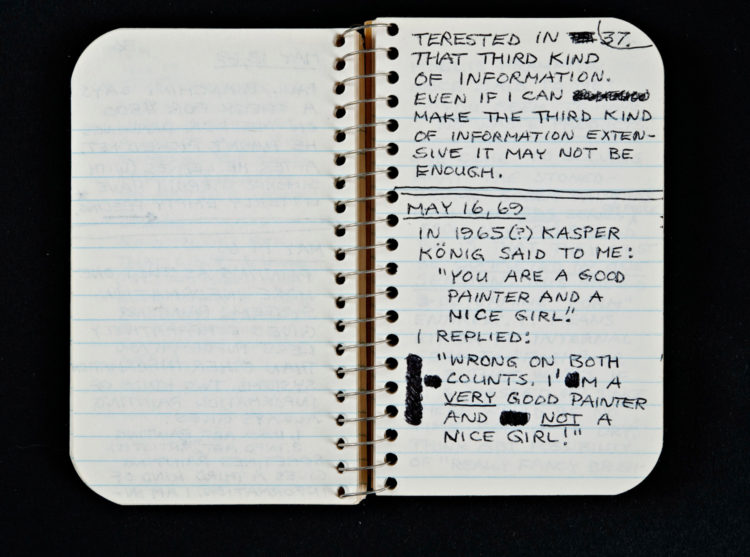

Born in Las Palmas (Canary Islands), she studied piano at the Real Conservatorio Superior de Música in Madrid and then graduated from the Universidad de Madrid with a degree in political science in 1963. While she never had any official training in the visual arts field, nevertheless, in 1970, she began her art career as a member of the emerging Conceptualist movement. Amidst the enormous social upheaval of that time, she was attracted to the anti-Franco struggle and forged a clear political awareness of the situation under his rule. This understanding found an outlet in Conceptual art as a means of expression, exposure and reflection. Founded a decade earlier, Conceptualism produced a brand-new landscape of experimentation. Among other things, it argued for the dismantling of the artwork and the emergence of the body, representing a radical rupture with the Modernist canon.

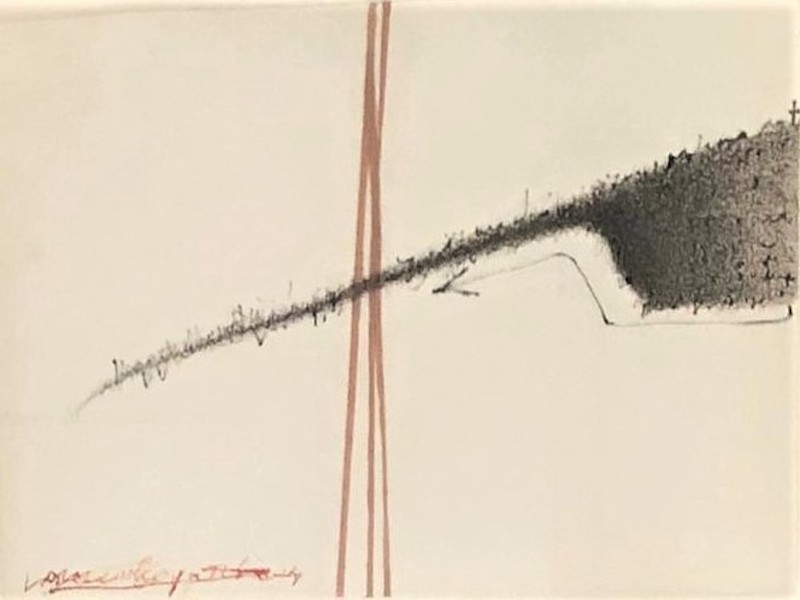

C. Jerez spent her early period examining the question of the mass media. She wanted to understand what they silence and what they show, and how they construct these elisions. An example is Seguimiento de una noticia [Tracking a News Item, 1977], an installation appropriating the front pages of a mass-circulation daily newspaper covering the tragic “Vitoria events”, the police murder of five workers during a protest demonstration in that city. The piece brings out how the newspaper gradually stopped covering the case, expelling it from the public space and burying it in oblivion. Also notable here is her thinking about how censorship works, not only in terms of its judicial forms but also self-censorship. She returned to these ideas in Textos autocensurados [Self-Censored Texts, 1976], an artist’s book in which texts have been rendered illegible – stained, erased, and hidden by the artist’s own hand. C. Jerez uses these procedures to signal the processes of self-imposed silencing.

She began to broaden her choice of media in the 1980s with the use of sound art, performance and Net.art. A relevant example of this is the action Música para la memoria de un encuentro [Music for the Memory of an Encounter, 1984-1986] where she probes the memory of an encounter with herself, subsequently “summarised” in an eponymous installation. Particularly notable are the pieces she made with the composer, sound and multidisciplinary artist José Iges (b. 1951). Starting in 1989, they explored our aural and technological environment in works like El ojo de Polifemo [The Eye of Polyphemus, 1997-1998], a complex video installation about contemporary surveillance systems.

C. Jerez’s body of work continues to be underrecognised. Nevertheless, her exhibition at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (2020-2021) is the culmination of a process of reconsideration of her work in Spain. In recent years, she has received prestigious awards such as the Premio Nacional de Artes Plásticas in 2015 and the Premio Velázquez in 2017. Her work is on view at various museums, including the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende in Chile and the Museo de Arte Moderno in Equatorial Guinea.

A notice produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2021