Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster

Films : Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Dijon, Les Presses du réel, 2003

→Morgan Jessica (dir.), Dominique Gonzales-Foerster : TH.2058, cat. expo., London, Tate Modern, (13 October 2008 – 13 April 2009), London, Tate Publishing, 2008

→Lavigne Emma (ed.), Dominique Gonzales-Foerster : 1887 – 2058, exh. cat., Centre Pompidou, Paris (23 September 2015 – 1st February 2016), Paris, Centre Pompidou, 2015

Expodrome, Musée d’Art moderne de la ville de Paris, 13 February – 6 March 2007

→Dominique Gonzales-Foerster : TH.2058, Londres, Tate Modern, 13 octobre 2008 – 13 avril 2009

→Dominique Gonzales-Foerster : 1887 – 2058, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 23 September 2015 – 1st February 2016

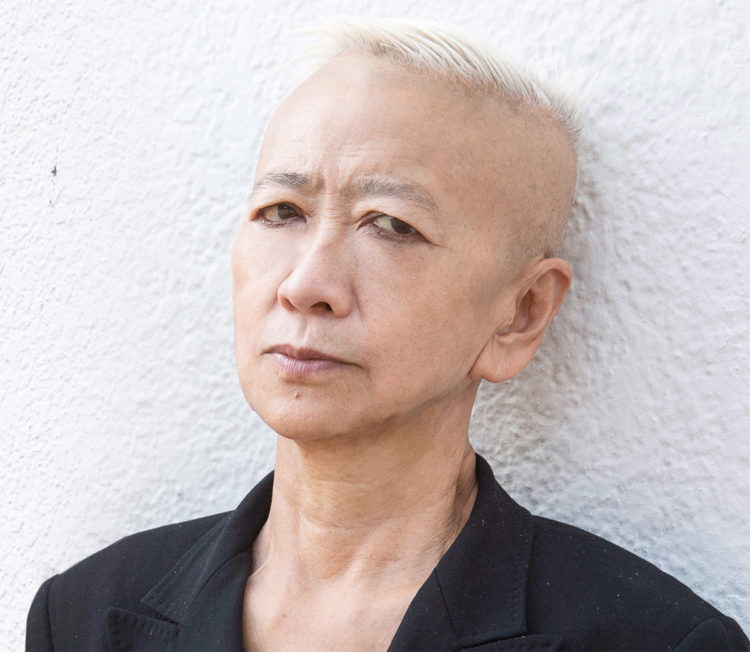

French visual artist and film-maker.

From the earliest biographical spaces in the early 1990s (the “portraits” and the “bedrooms”), to the open environments of this last decade, the plurality of worlds remains Dominique Gonzales-Foerster’s primary discovery—her “astronomical” position in art. Her projects thus shift from one field to another, from art to film, and from literature to architecture, all so many worlds which she does not regard as separate, but as transfer zones, and temporary halts. At a very early stage, film and words had an important place in her imagination, acting like entrances, areas of influence, and horizons. The artist does not, however, borrow from film, literature or art history: she inhabits their territories. These entrances of film, literature and architecture are never clearly indicated, and, even if we may rely here and there on a title, or an evocative element, they determine the structure of her pieces, and their arrangements, leaving nothing more than imprints, and sensations of films, books, and travels (as she also likes talking of “art sensations”). Throughout her oeuvre there is first and foremost an act of tracing, an attempt to explore a foreign space, or make the portrait of a city (the film trilogy Riyo, Central, Plages, 1999-2001). This crossing of signs and landscapes is not the same as colonizing them, but simply means going ahead of the images, to see from what they are born, from what experiences.

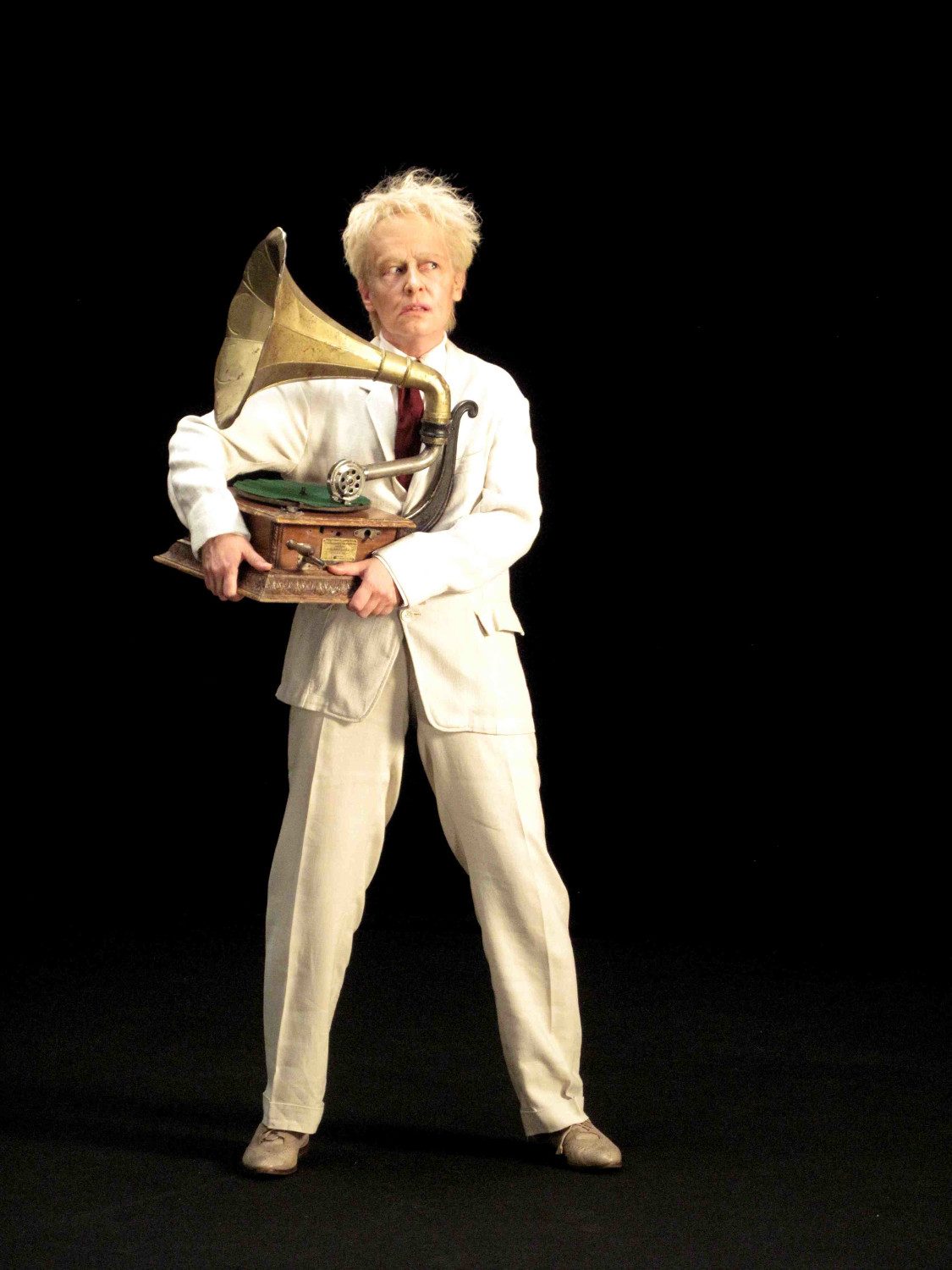

Gonzales-Foerster does not try her hand at either fiction or the documentary. Her work is situated on the boundary between the image and the visible. In the place of something missing, in the murkiness and confusion of the different levels of reality, precisely where information becomes dissolved, is lost, and links back up with the subject of a conquest. In her “programmatic” environments (Cosmodrome, produced with the musician Jay-Jay Johanson in 2001), and in her public parks (A Plan for Escape, for documenta 11 in Kassel in 2002; Roman de Münster for SKulptur Projekte Münster in 2007), we see how the system of the exhibition is replaced by the narrative of a landscape, caught in a dialectical system, a sort of “non-site”, thus a fragment, a formation that is closed, inner, delimited, and concentrated, which leads towards a “site”, another exterior, peripheral, and boundless space. The park, the beach, and the garden are among these non-sites, chronic spaces, cut-out parts of the world. We find all these dimensions again in her museum projects and her first solo show, Expodrome, at the City of Paris Museum of Modern Art, in 2007, for which the artist put together an “exhibition crew”, a collaborative principle which refers to the early days of a collective adventure in Grenoble, when she was exploring a new exhibition vocabulary, with Pierre Joseph, Philippe Parreno, and Bernard Joisten, a bit like a film crew. Expodrome was a turning point, which gauged the architectural curve of the space of the ARC (Animation Research Confrontation), and of light and its scale, questioning the notion of artwork, and re-enacting the classical conditions of the exhibition. Devised as an open and novel experience, the project took into account the time of the visitor’s movements, summoned as he was to have a “narrative journey”, alternating contemplation, reading, walking, and film.

Another significant turning point in her output was the spectacular environment TH.2058 (2008), conceived for the Tate Modern’s The Unilever Series programme, where the artist projected a science fiction landscape, a climatic revolution, and a journey in time. In 2058, a permanent deluge strikes London, a disturbance producing strange effects on people and things: these urban works start to grow like gigantic tropical plants, and become monumental. “To put an end to this growth, it has been decided to put them away inside, among the hundreds of bunk beds which, day and night, house refugees or people fleeing from the rain.” The initial scenario describes the cinematographic nature of the experience to come, while the curtain of red and green plastic strips, which spectators pass through to access this refuge, confirms the theatricality of the very principle of the exhibition, thus introducing the imprecise image of the access to a hangar providing health care. Then come the sensations: the permanent sound of heavy rain, the metal and the yellow and blue colours of the bunk beds, the presence of books arrayed on these beds, the monstrousness of these sculptures by Louise Bourgeois, Calder and Claes Oldenburg, the memory of the last film, and the endless daydream of a world without sun.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, elle@centrepompidou, ina.fr

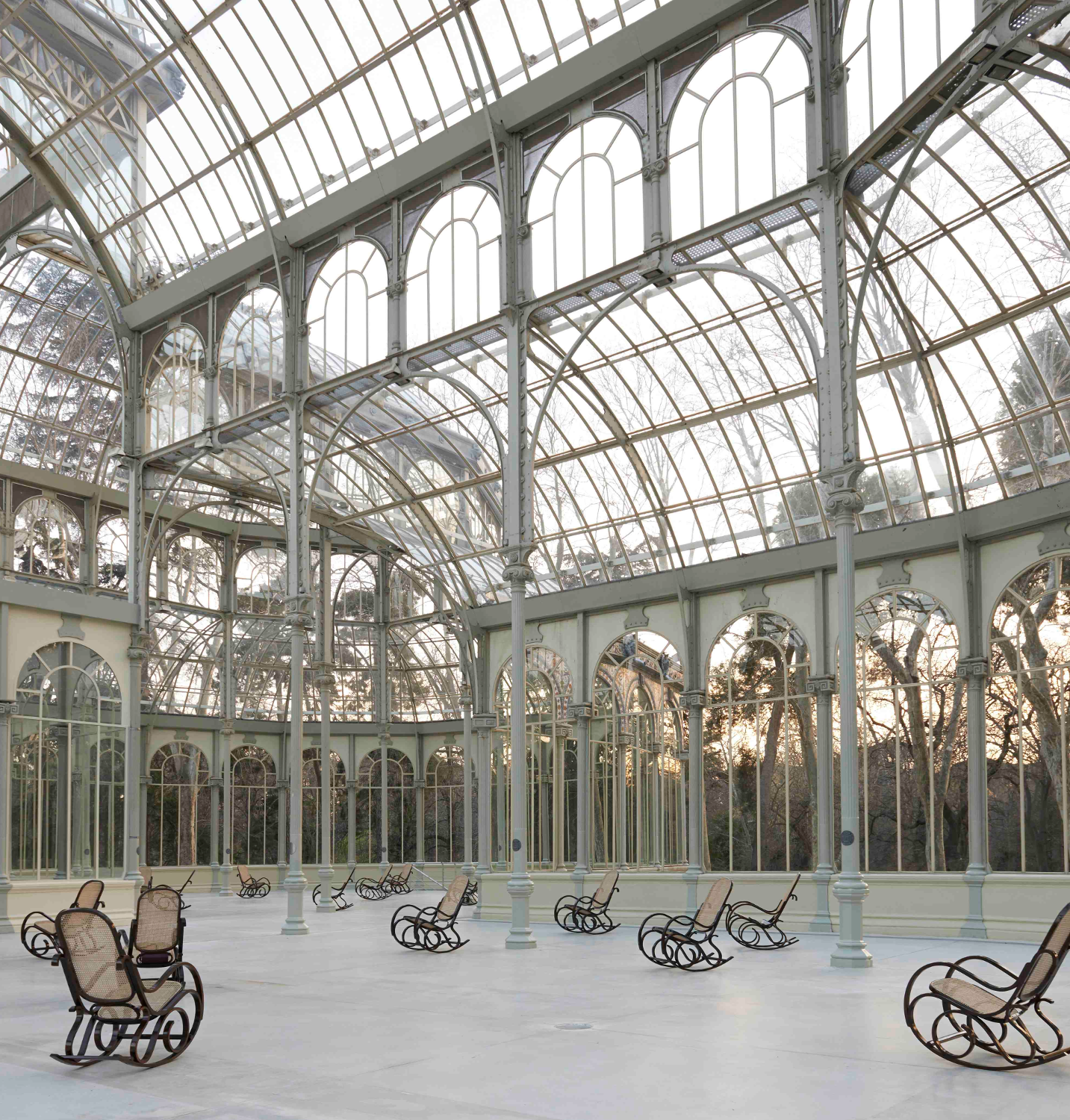

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, elle@centrepompidou, ina.fr  Gonzalez-Foerster installation at Tate Modern's Turbine Hall

Gonzalez-Foerster installation at Tate Modern's Turbine Hall