Fiona Tan

Fiona Tan: Geography of Time, exh. cat., Nasjonalmuseet – Museet for samtidskunst, Oslo ; Mudam, Luxembourg ; MMK am Main, Frankfurt ; Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Tel Aviv (2015 – 2017), London, Koenig Books, 2015

→Tan Fiona, Vox populi, London, Book Works, 2012

→Provenance, exh. cat., Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (2008), Amsterdam : Rijksmuseum, 2008

Geography of Time, Tel Aviv Museum, Tel Aviv, 11 February – 24 June 2017

→Terminology, Metropolitan Museum of Photography, Tokyo ; National Museum of Art, Osaka, 2014

→Fiona Tan, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, 2005

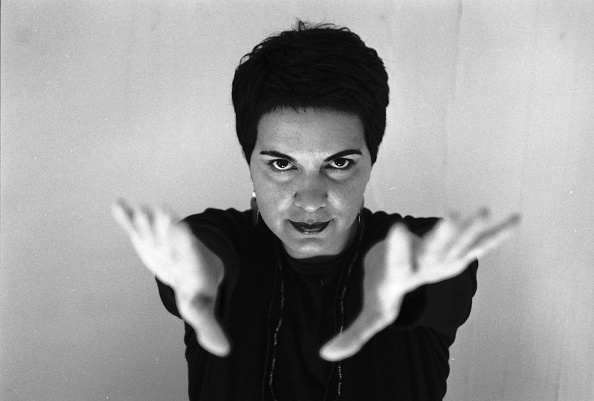

Australian filmmaker and photographer.

The daughter of a Chinese diasporan and an Australian mother, Fiona Tan was born in Indonesia, grew up in Australia, then lived in Europe until the age of 18. The meanderings of her life reflect a complex geopolitical history. These few biographical elements, which she illustrated in her documentary film May You Live In Interesting Times (60 min, 1997), are indicative of the importance of “dispersion” – of stories, modes of representation, techniques, and identities themselves – in her work. The installation – the artist’s favourite medium – is an intricate assemblage of images and sounds, which involves the audience in an open interpretation process. Since the early 1990s, the young artist’s use of borrowed images (Totenklage/Lacrymosa, 1993; Facing Forward, 1999; News from the Near Future, 2003) indicates that this very image – photographic, cinematographic, or video – represents for her the embodiment of the idea of wavering memory, which she commentates in all her pieces in one way or another, as well as a memory of forgotten tales – mainly those seen in early ethnographic films, which she reworks in an attempt to deconstruct the supposedly objective or scientific vision that these films convey.

The countermemory she puts together stems from the images she finds, the ones she makes herself, or the creation of which she oversees – they all establish points of contact between our present and the past, with its distant cultures and obsolete techniques. Each time, the installation presents itself as a space where visual data is recorded and stored, like a moving archive. Documentary cinema occupies a central position in the artist’s approach, as she would say herself: “My whole work reflects and relies on the principles of documentary film (…) almost all my film and video installations – whether they contain borrowed images or footage I shot – include documentary content. What interests me in cinema, video, and photography is the genuine and anthropological aspect they contain.” Intimate stories, salvaged and recycled films (inspired by the found footage trend), scientific pictures (Linnaeus’ Flower Clock, 1998), television footage (Stolen Words, 1991), and filmed performances involving the artist’s body (Slapstick, 1998): the life work of the video artist resembles a vast anthropological study that develops all the infinitely varied ways of depicting, and therefore questioning, reality.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Fiona Tan at Mudam, Luxembourg

Fiona Tan at Mudam, Luxembourg