Germaine Krull

Krull Germaine, Métal, Paris, Libraire des arts décoratifs, 1929

→Sichel Kim, Germaine Krull: photographer of modernity, Cambridge, MIT Press, 1999

→Germaine Krull, Métal y la fotografia industrial 1920-30, exh. cat., Guillermo de Osma Galeria, Madrid (29 June – 27 July 2011), Madrid, Guillermo de Osma Galeria, 2011

Germaine Krull, Cinémathèque française, Paris, 1967

→Germaine Krull, photographie 1924-1936, Musée Réattu, Arles, 2 July – 30 September 1988 ; Muée d’art moderne, Céret, 15 November 1988 – 15 January 1989 ; Musée Nicéphore Niepce, Chalon-sur-Saône, Spring 1989

→Germaine Krull (1897-1985). Un destin de photographe, Jeu de Paume, Paris, 2 June – 27 September 2015

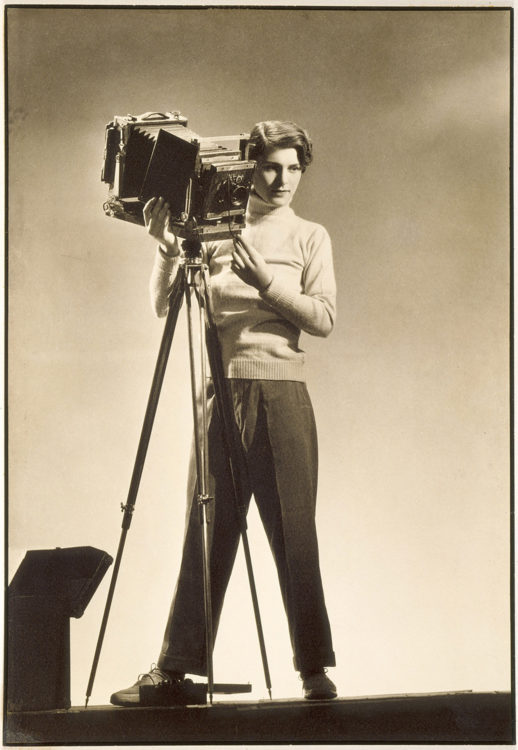

German naturalised French photographer.

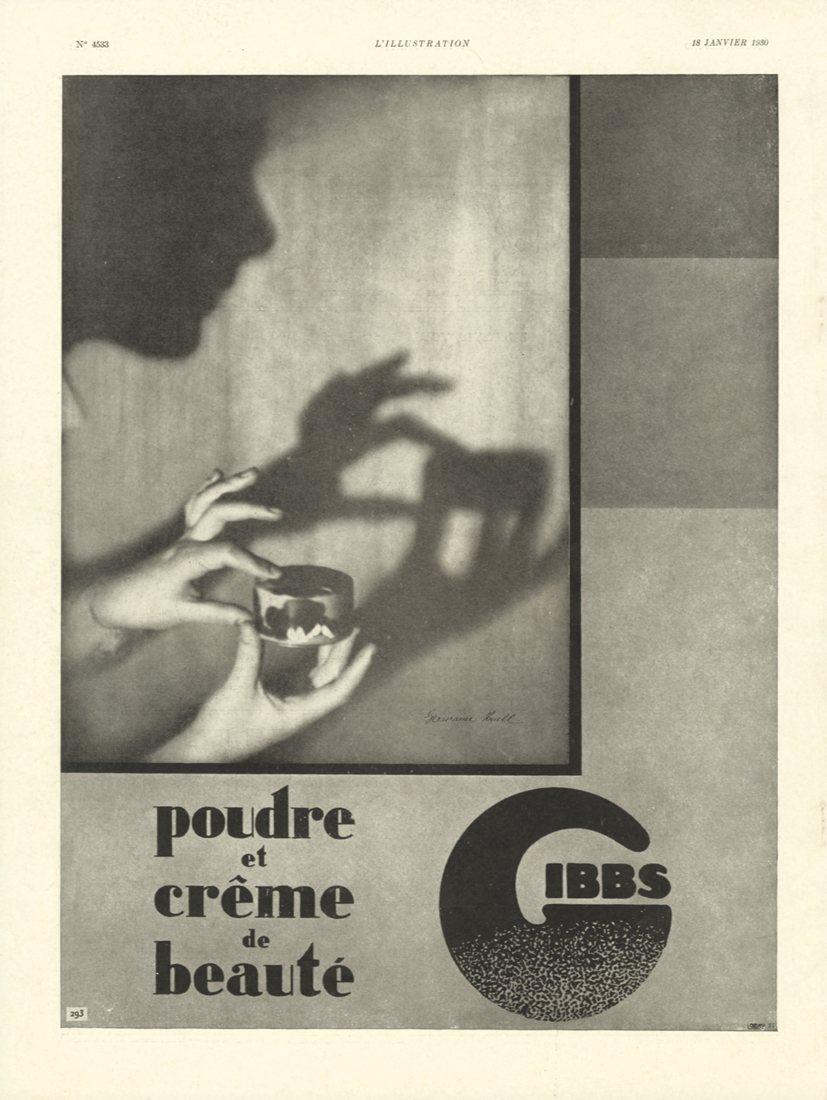

Considered in France as the representative of (New Objectivity), a German realist movement that introduced geometric motifs to photography, Germaine Krull remains known as the woman of Métal, named after one of her prestigious series. Born in Germany she had a hectic youth: expelled from Munich in 1918 thanks to her revolutionary activities, she moved to Berlin and began specialising in portraiture. Well integrated in the Berlin art scene, she published in literary magazines and photographed buildings and train tracks from new angles, focusing predominantly on the geometry of the city. From 1921 she lived in the Netherlands, where from 1924 to 1925 she and her future husband, filmmaker Joris Ivens, used industrial architecture as their main subject. She arrived in Paris in 1926, connecting with the Parisian artistic scene, working in fashion with Sonia Delaunay, and in commercial and industrial photography for Peugeot and Shell. With the help of Robert Delaunay she exhibited her series Métal – comprised of Dutch bridges, low-angle shots of the Eiffel Tower and images of automobiles – at the Salon d’automne. The 64 plates were published under the same name by the publisher Calavas in 1927. Despite the mediocre printing quality, Métal was a success and appeared to be the manifesto of a new vision. These reversed photographs reveal an interplay of volumes, abstract details and geometric motifs, and through their unusual cropping constitute a “manifesto of the modern perspective”, according to Christian Bouqueret, and symbolise the new aesthetic awareness of industrial beauty.

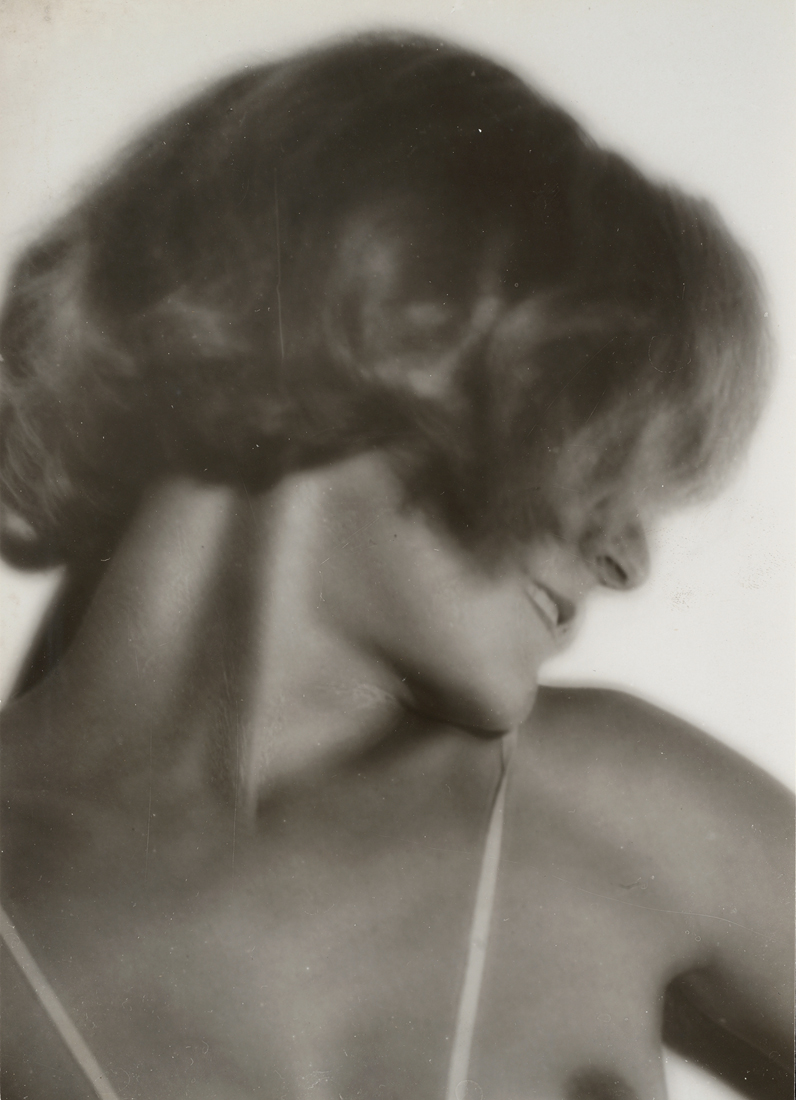

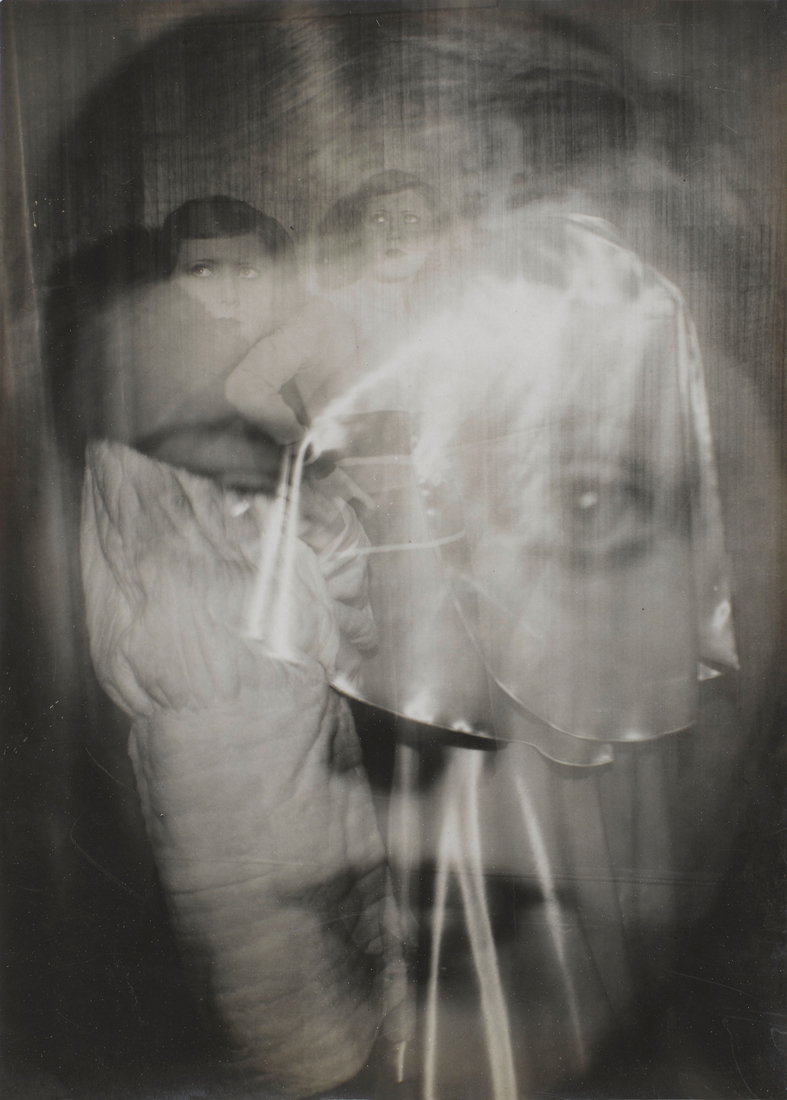

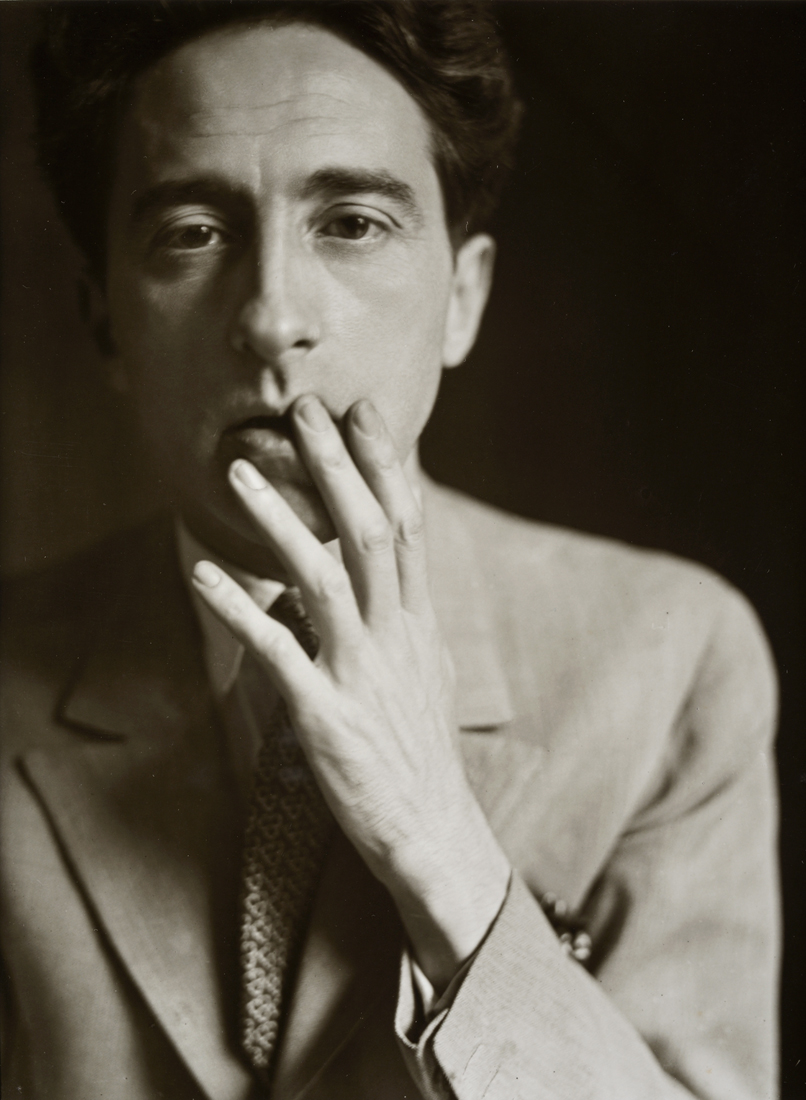

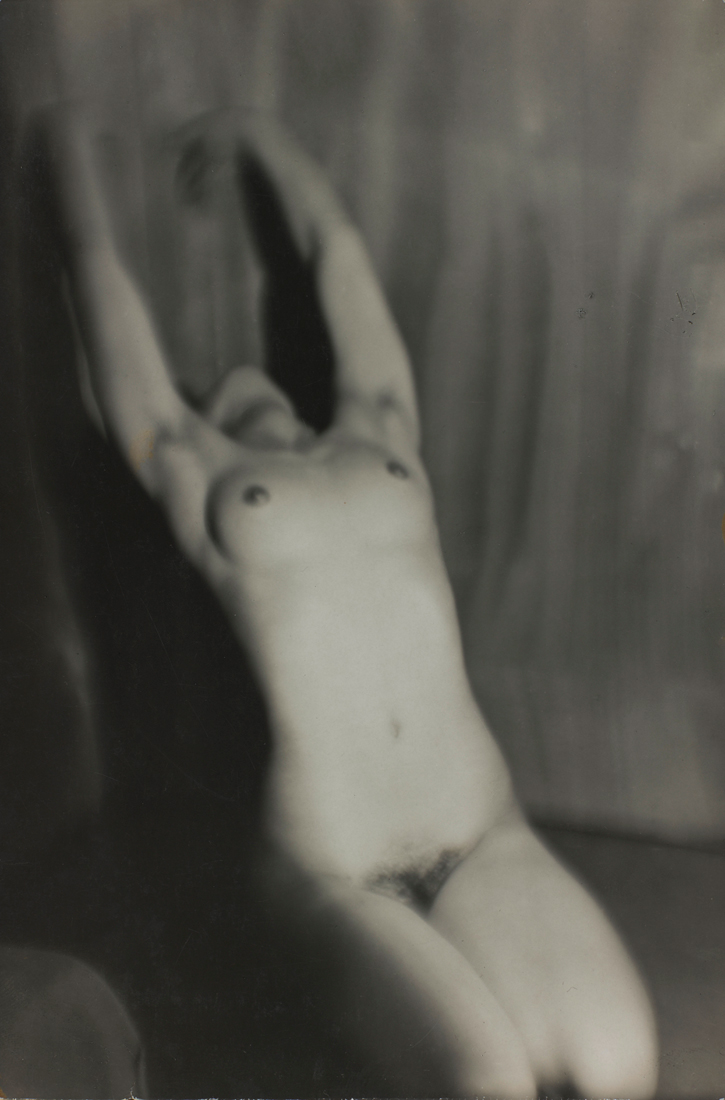

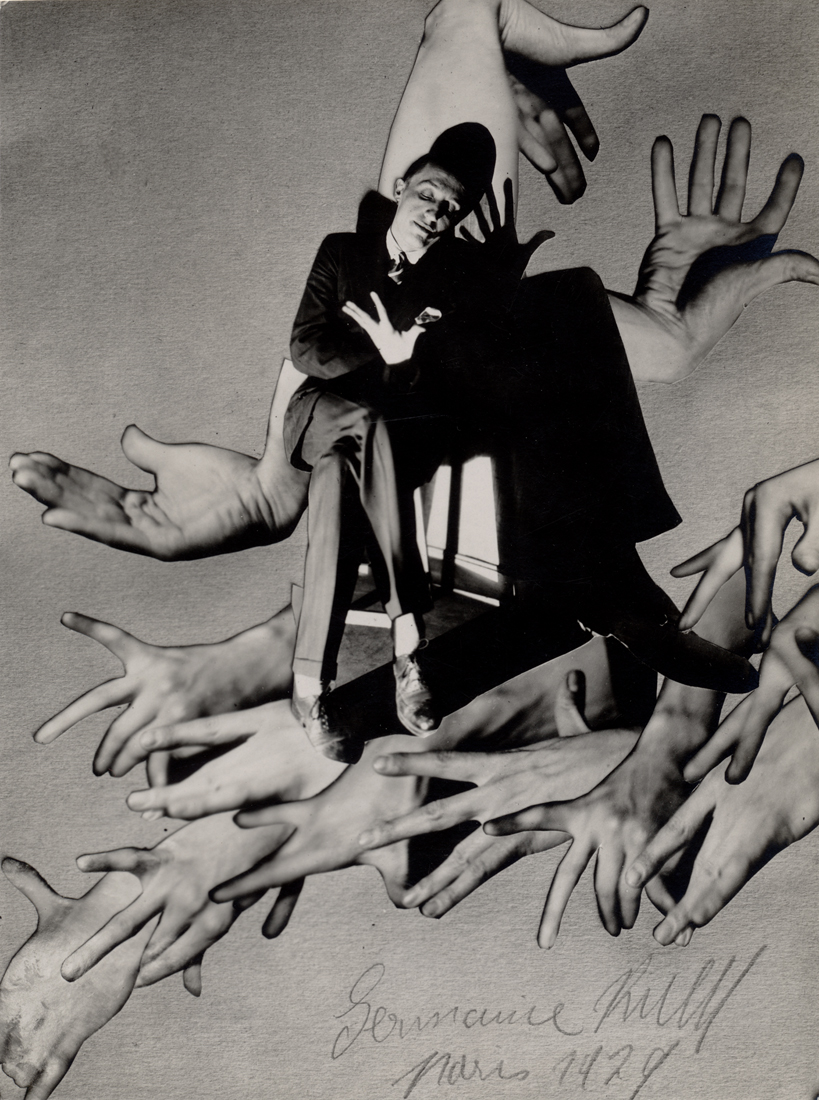

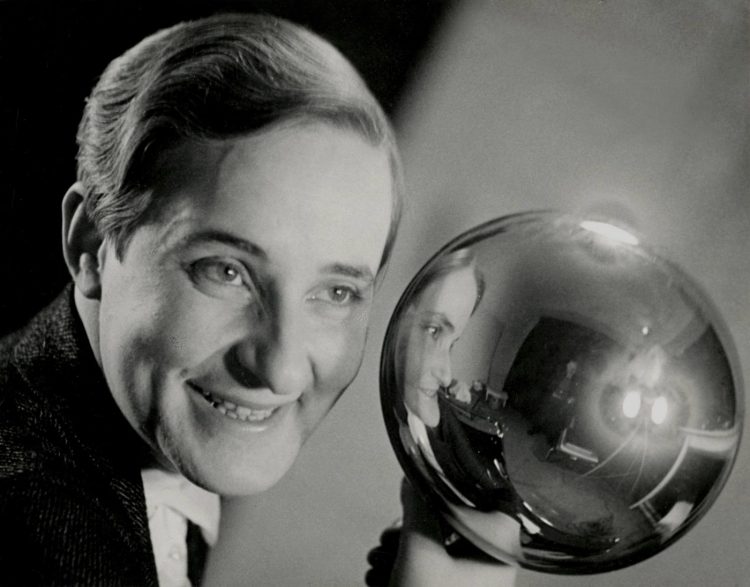

During the same period, her nude photographs of the young model Assia show fragments of the body that slip into abstraction (1930). At the end of the 1920s she had gained recognition and Walter Benjamin included her in A Short History of Photography (1931). She appeared thus as the leader of the Nouvelle Vision (New vision), a movement that considered photography, with its technical and artistic possibilities, as giving a new perspective of the world. Her portrait of filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein (1930) is emblematic of the style: tight framing, low-angle lighting and theatricality. In 1928 she exhibited at the first Salon des indépendants de la photographie, known as the Salon de l’escalier, in Paris, at Film und Foto in Stuttgart in 1929, and later in Munich and Brussels. She spent time with Berenice Abbott, André Kertész and Man Ray, and worked in close collaboration with Eli Lotar with whom she realised photomontages and exchanged negatives. During the same period, she worked for illustrated magazines (Vu, Voilà, Détective, Jazz) at the height of their golden years. She realised series on diverse subjects, such as the banks of the Seine, the Spanish Revolution and Javanese dancers. Her preference was for the Paris of Francis Carco and Pierre Mac Orlan – a marginal, working-class Paris. She photographed the zone and created a reportage on the homeless. She also participated in a series of books on the capital (Paris by Mario von Bucovich, 1928, 100 x Paris, 1929). In 1931 a monograph titled Germaine Krull was published in the collection “Photographes nouveaux” with texts by Pierre Mac Orlan was a “true consecration”, of her, as C. Bouqueret wrote. She then travelled throughout Europe and moved to the South of France where she conducted local reports. A discreet activist and friend of André Malraux, she emigrated to the United States in 1940, then to Brazil, and joining the Resistance. She directed the photographic service of Free France and photographed General De Gaulle in Algiers. After 1945 she become a war reporter in Germany, Italy and Indochina for various newspapers and illustrated magazines. She then left for Thailand and India, returning to Germany just before her death. Thanks to A. Malraux, a retrospective of her work was presented at the Cinémathèque Française in 1967, and some of her photographs were exhibited at Documenta 6 in Kassel in 1977. During her lifetime, she did not receive recognition as a photographer, probably because of the loss of her old negatives, recently found, and the dispersion of her production during the interwar years. However, internationally known for her engagement and personality, she has influenced entire generations of photographers.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2020