Huong Dodinh

Catherine David, Marc Glimcher, Huong Dodinh: Transcendence, interview by Olivia Sand, exh. cat., Pace Gallery, New York [May 3– August 16, 2024], New York, Pace Publishing, 2024

→Hervé Mikaeloff, Amin Jaffer, Gabriella Belli, Huong Dodinh, Ascension, exh. cat., Museo Correr, Venice [April 23– November 6, 2022], Paris and Venice, Cassi Edition, 2022

→Sophie Makariou, Hervé Mikaeloff, Huong Dodinh: À la conquête de la lumière, exh. cat., National Museum of Asian Arts – Guimet, Paris [October 20–December 13, 2021], Paris Hemeria, 2021

Huong Dodinh: Transcendence, Pace Gallery, New York, May 3– August 16, 2024

→soft and weak like water, 14th Gwangju Biennale, Buddhist Temple Mugaksa, Gwangju, South Korea, April 7–July 9, 2023

→Huong Dodinh: Ascension, Museo Correr, Venice, April 23– November 6, 2022

→Huong Dodinh: A la Conquête de la Lumière, National Museum of Asian Arts – Guimet, Paris, October 20–December 13, 2021

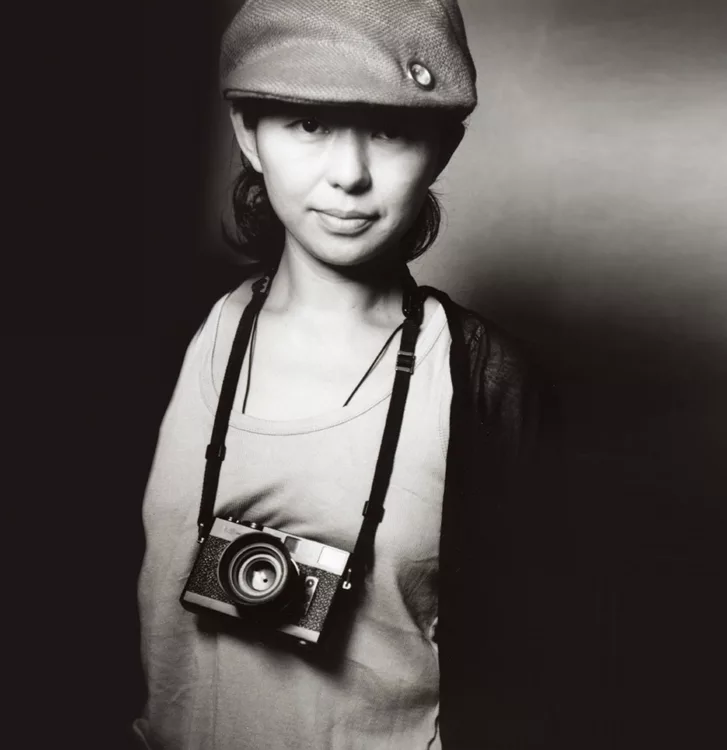

Franco-Vietnamese painter.

Huong Dodinh left Vietnam in 1953, the family moved definitively to France, having fled the war in Vietnam. For some years after their arrival, H. Dodinh, her parents and siblings experienced hardship and unhappy placements, and at the age of eight she was sent to boarding school near Rambouillet. Here, she experienced rigorous discipline and the French winter, but also discovered snow, an illuminating moment for her that would play a decisive role in her move towards painting. The snow seemed to be the light that had been missing from this new country – today, H. Dodinh still definitively describes herself as “not from here”. The snow allowed her to acclimate herself, creating an intense dazzling effect reminiscent of the humid light of Vietnam and her early childhood. And so it became her language, and stayed her language, even after she had mastered French. Already, through paint, she had started to express a kind of seclusion within her own space, her own country, with the first box of gouaches presented to her by her parents. During a period of illness (1961–1964), H. Dodinh pursued this desire further, and resolved to become a painter despite her father’s reluctance. She studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris during the latter half of the 1960s. She met a young Vietnamese chemistry student, Lan Do Dinh, and they married in 1970. Though not contributing to the actual making of H. Dodinh’s paintings, L. Do Dinh helped her understand more about the technical properties of the materials. In the shadow of the violence of the Vietnam War and the events of May 1968 in France, H. Dodinh strove more than ever to cultivate her inner country: painting.

Parallel to her work as a painter, H. Dodinh taught fine arts. In the 1980s and the early 1990s, she participated in a number of salons, taking home first prizes (Deauville, Cannes, Paris, Toulouse etc.) and drawing the attention of gallerists (Marie-Thérèse Cochin, Pierre Matisse, Peter Meyer…). In 1994, an encounter with the Dominican Father Jacques Laval, a close friend of several artists, proved decisive: he commissioned a work from her for the Saint-Jacques convent in Paris, which led to her exhibiting work at the FRAC Champagne-Ardenne in Reims.

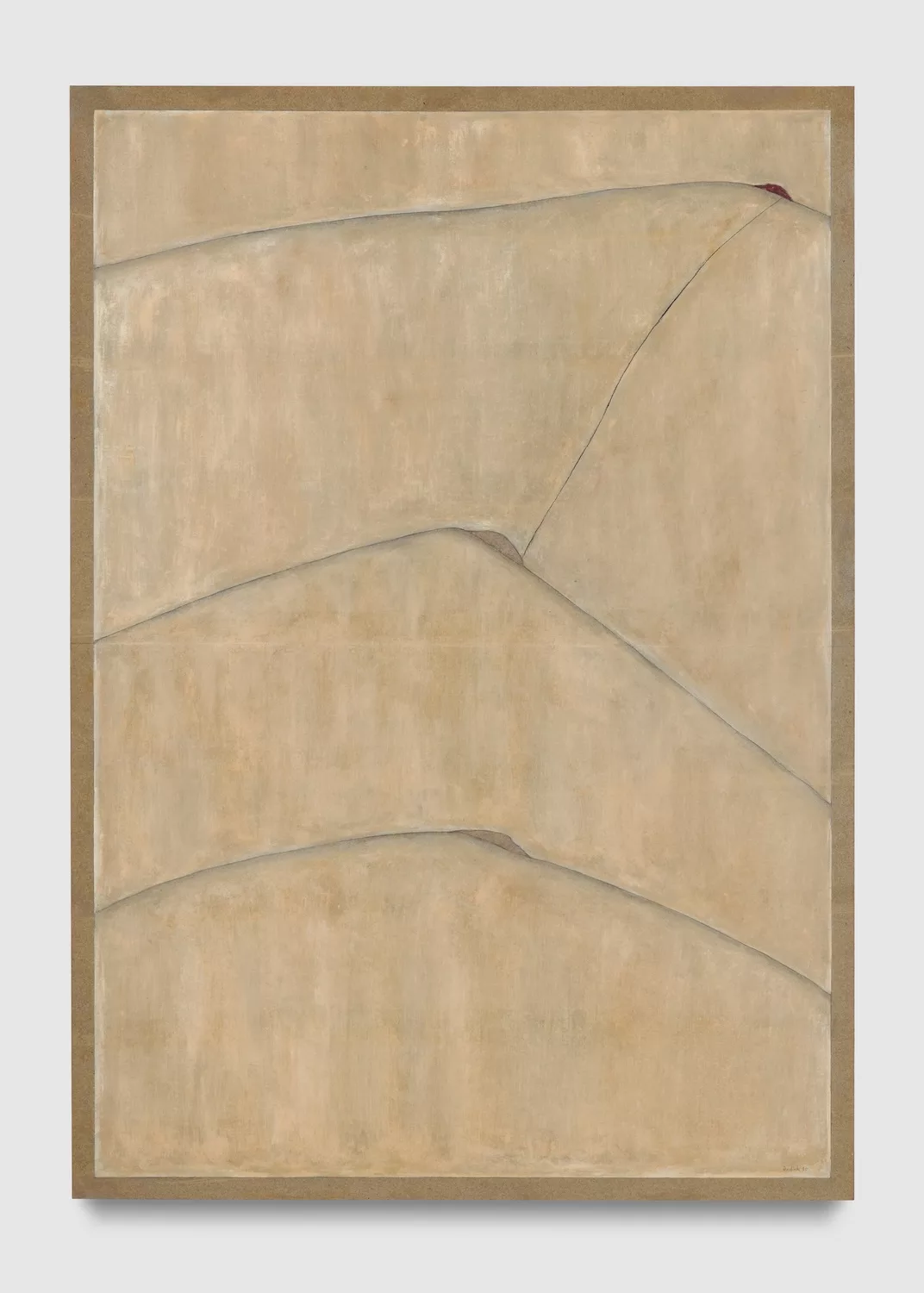

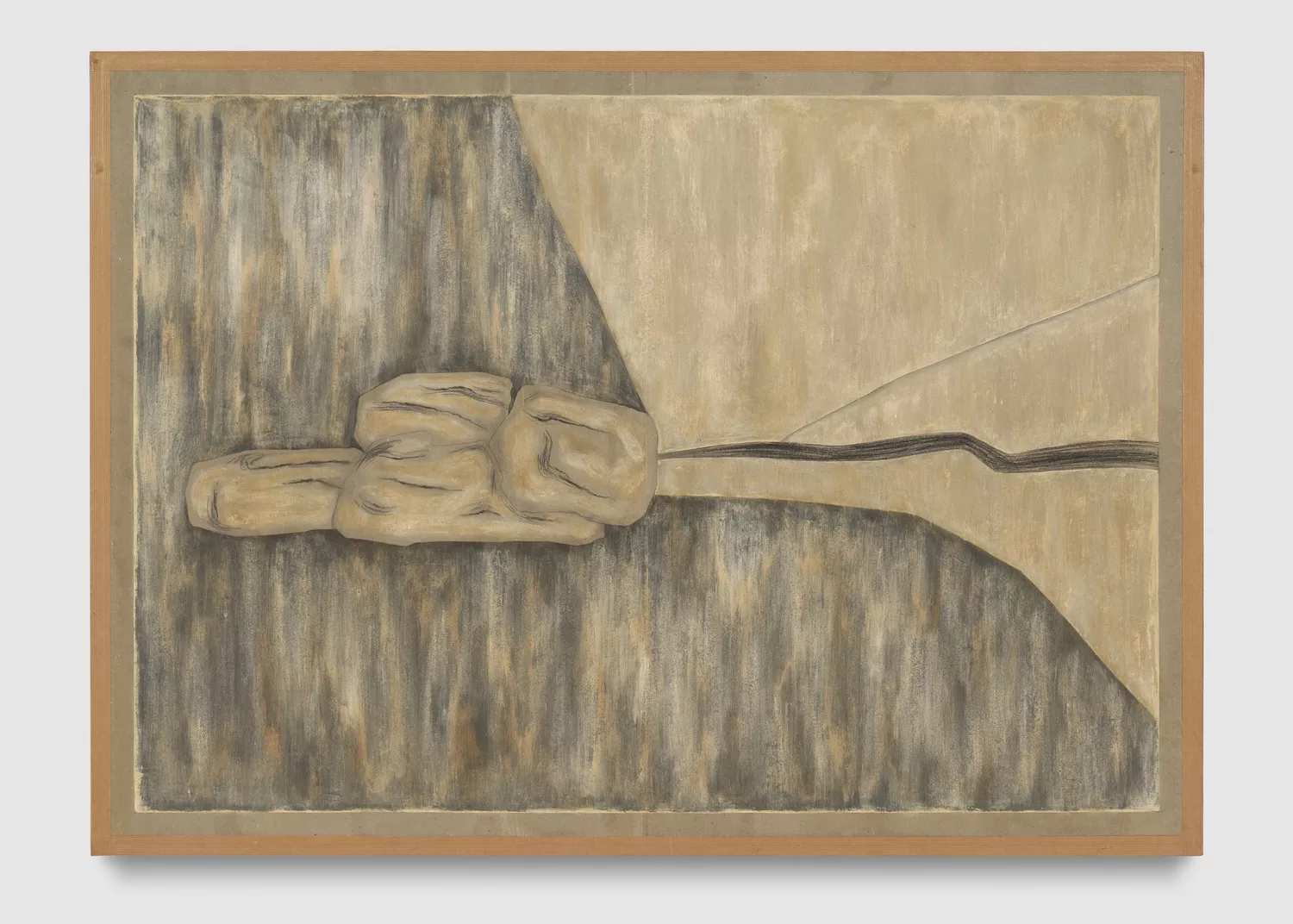

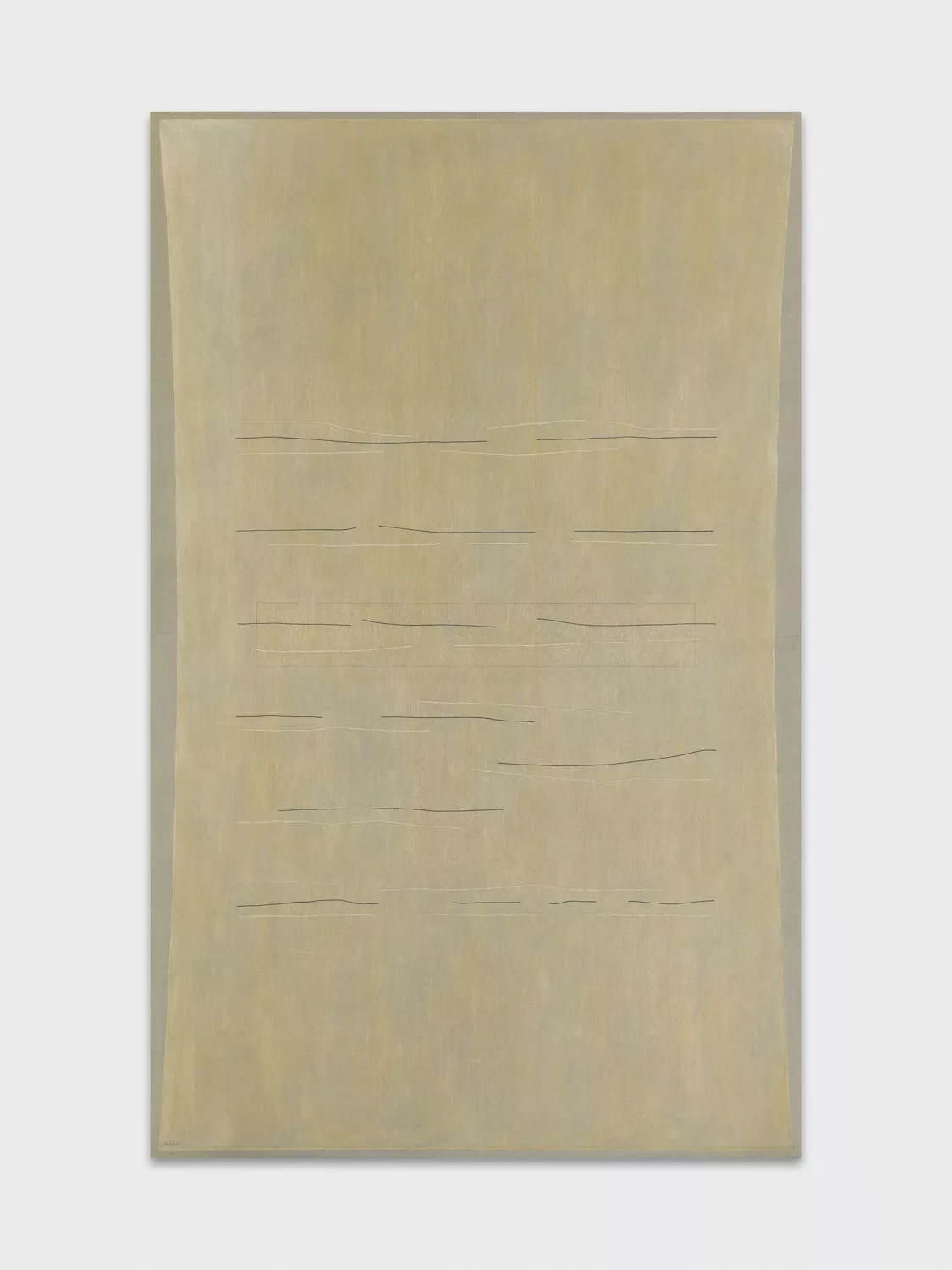

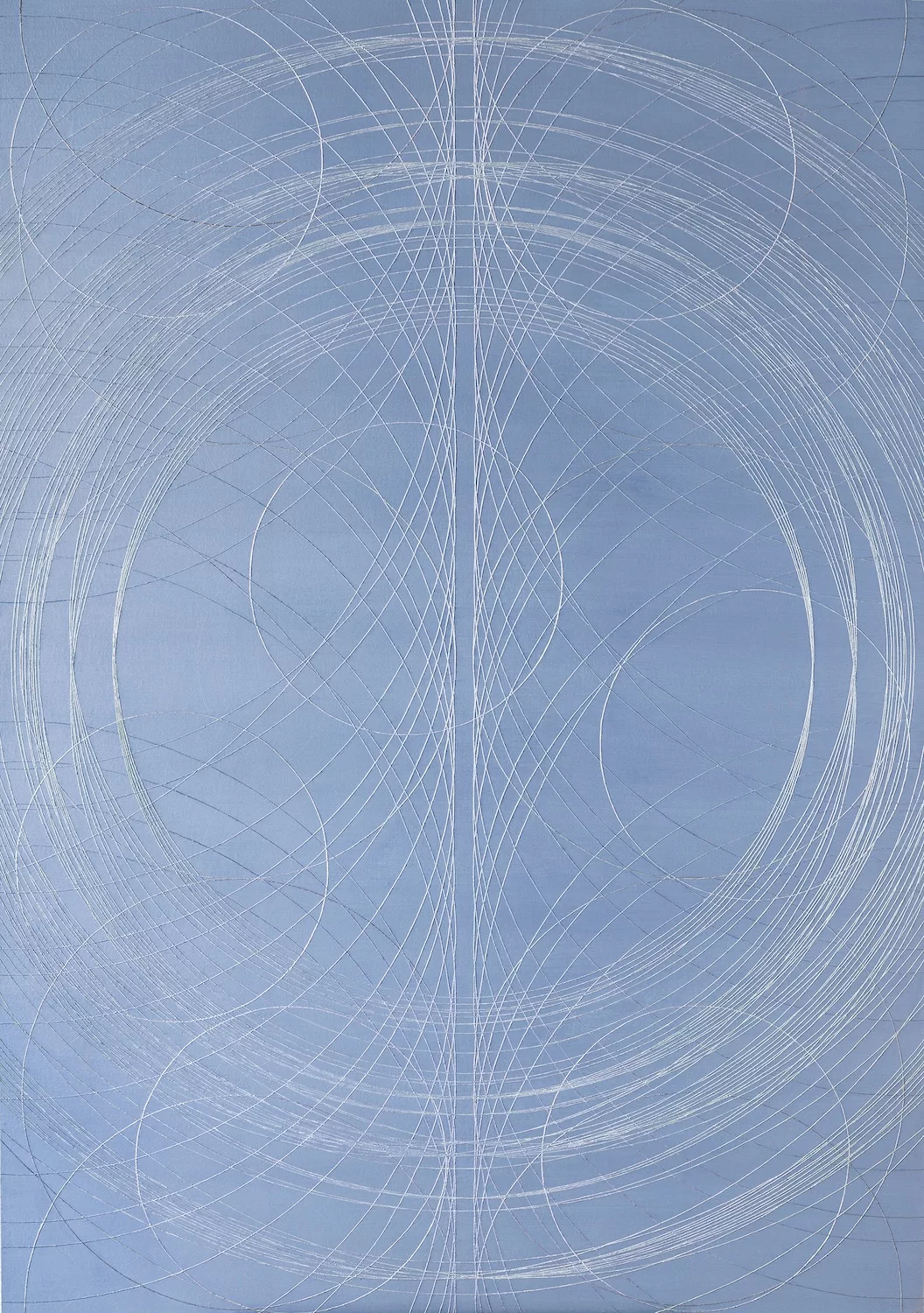

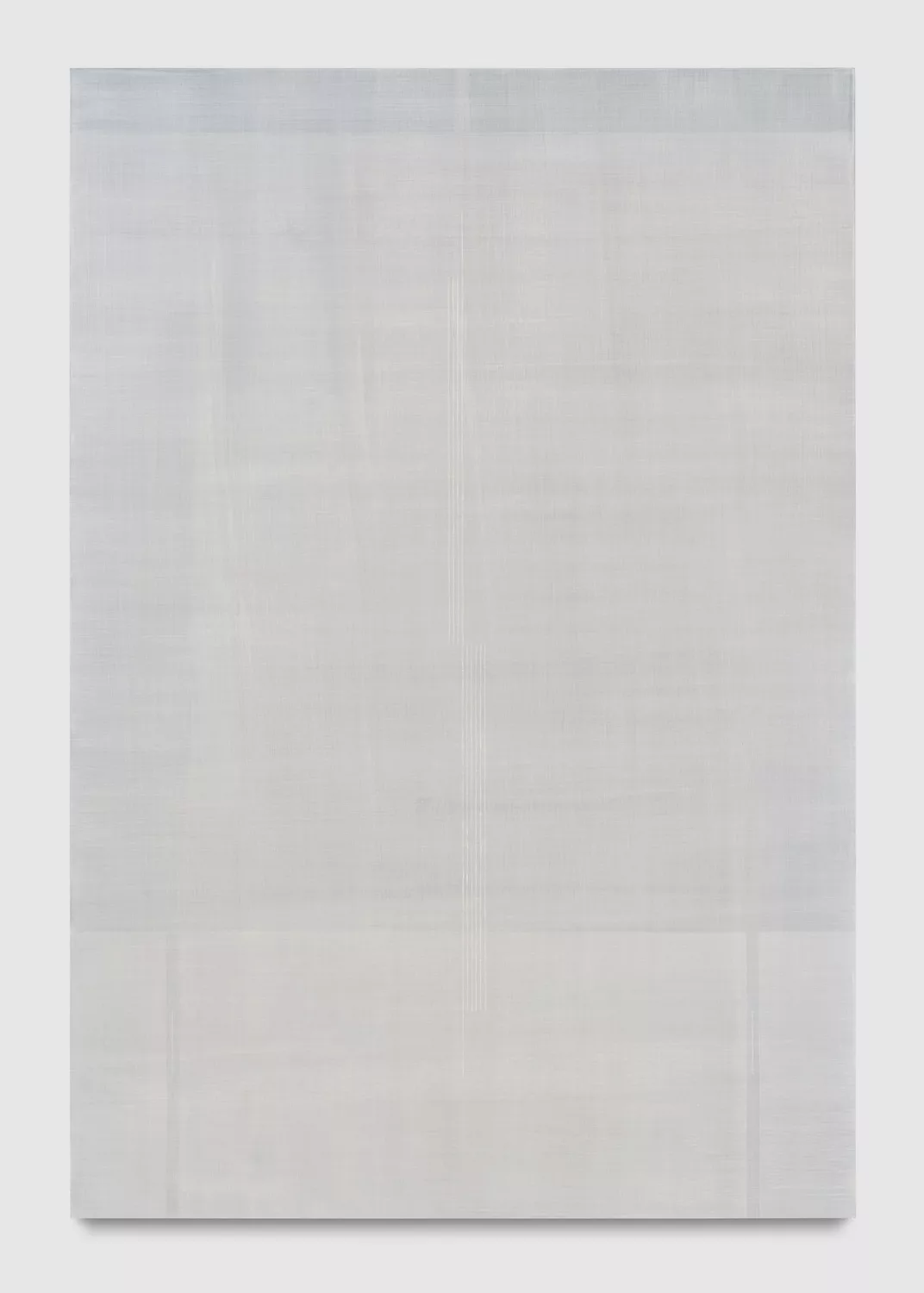

Towards the end of the 1990s, H. Dodinh’s work began to circulate beyond the borders of France, and she exhibited several times in Germany. However, she was still painting in her artist’s garret on a sixth-floor apartment in Paris and not widely exhibiting her works. She prepared her own colours and stretched her own canvases. Each of these operations is a part of her intimate creative process, her point of entry into “this painting here”, into the process of creation, irreducible. In her light-filled studio, where she arrives early each morning, forty years’ worth of work accumulates. She even paints on the floor. Her work proceeds with the focus of her whole being, allowing her to draw perfect circles with a free hand, in one gesture, with lines that imperceptibly modulate the silent and melodic space that is the canvas. It is an art of numbers that carries nothing of intellectual coldness, but rather a profound sense of harmony and meditation, which reaches us through the patient superimposition of veils of paint that form a geometry of interstices.

In her work T2, 1992, H. Dodinh’s palette vibrates with the luminous mists of the country of her childhood: we make out an echo of monsoon rains falling in fine, dense sheets in the vibrating veils of superimposed natural pigments, a green becoming yellow. Broken horizontal lines in black and white are delicately laid over the veils – living lines that remind us of the strata formed by rice paddies in the Vietnamese landscape. We rediscover echoes of her very first pastels. Geometry has always been here, simplifying and clarifying her landscape. In N.H.N. 1, 2023, the symbol may have changed but we still hear the singular music of H. Dodinh, intact and merely modulated. A square format work, the colour range has passed towards a light mauve mixed with white and grey; the fine horizontals have made way for a play of squares and rectangles, juxtaposed as much as superimposed, occasionally punctuated by the discrete apparition of white marks. We barely make them out. But we rediscover that same sensation: space unparalleled, a canvas that knows no limits. A true “arrière-pays” opens before us, in the exact sense of the term as defined by Yves Bonnefoy: an arrière-pays of the mind that promises an endless journey as it conquers the geometric definition of space and the linear continuity of time.

Having been identified by the platform CMS Collection, H. Dodinh held her first major exhibition at the age of 76, at the Musée Guimet. She also joined the Pace Gallery, which promptly devoted two solo shows to her work.

Huong Dodinh: Revealing Light | Pace Gallery, April 2024

Huong Dodinh: Revealing Light | Pace Gallery, April 2024