Lola Cueto

Greet, Michele, “‘Exhilarating Exile’: Four Latin American Women Exhibit in Paris”, Artelogie, n. 5, 2013

→Duarte Sánchez, María Elena (ed.), Lola Cueto: trascendencia mágica, 1897-1978, exh. cat., Museo Casa Estudio Diego Rivera, Mexico City (2009), Mexico City, Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, 2009

→Flores, Tatiana, “Strategic Modernists: Women Artists in Post-Revolutionary Mexico”, Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 29., n. 2 (Fall – Winter, 2008), p. 12-22

Flores Mexicanas: Women in Modern Mexican Art, Dallas Museum of Art, February 16, 2020–January 10, 2021

→Lola Cueto: trascendencia mágica, 1897-1978, Museo Casa Estudio Diego Rivera, Mexico City, 2009

→Tapisseries Mexicaines de Lola Velasquez Cueto, Salle de la Renaissance, Paris, February 6-19, 1929

Mexican painter, printmaker, textile artist, puppeteer and teacher.

María Dolores Velázquez Rivas, better known as Lola Cueto, began her artistic practice in 1909 at the Academia de San Carlos when she was just twelve years old and continued her training at Escuela de Pintura al Aire Libre de Santa Anita. L. Cueto’s artwork, and eventual teaching practice, would come to embody concepts of national identity formed in the aftermath of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) and the “renaissance” in art and culture centred on a fusion of popular and modern aesthetics.

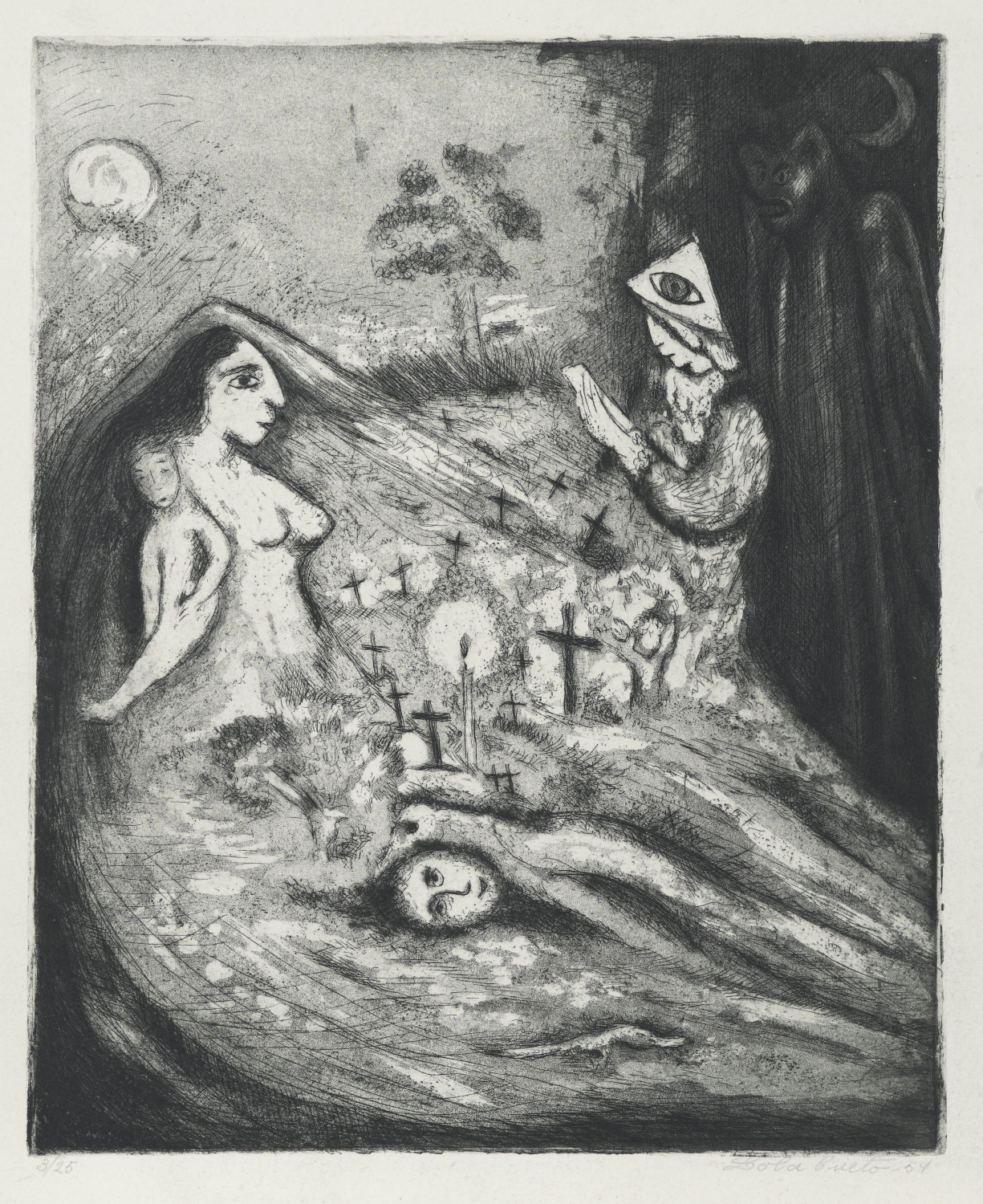

L. Cueto and her husband, the artist Germán Cueto (1893-1975), co-founder of the arts and literature movement known as Stridentism, were at the centre of avant-garde circles in post-revolutionary Mexico City. L. Cueto’s innovative approach to embroidery enabled her to make inroads with the male-dominated group that prioritised modern technologies and her works were often featured in the journal Horizonte, edited by the Strident poet Germán List Arzubide.

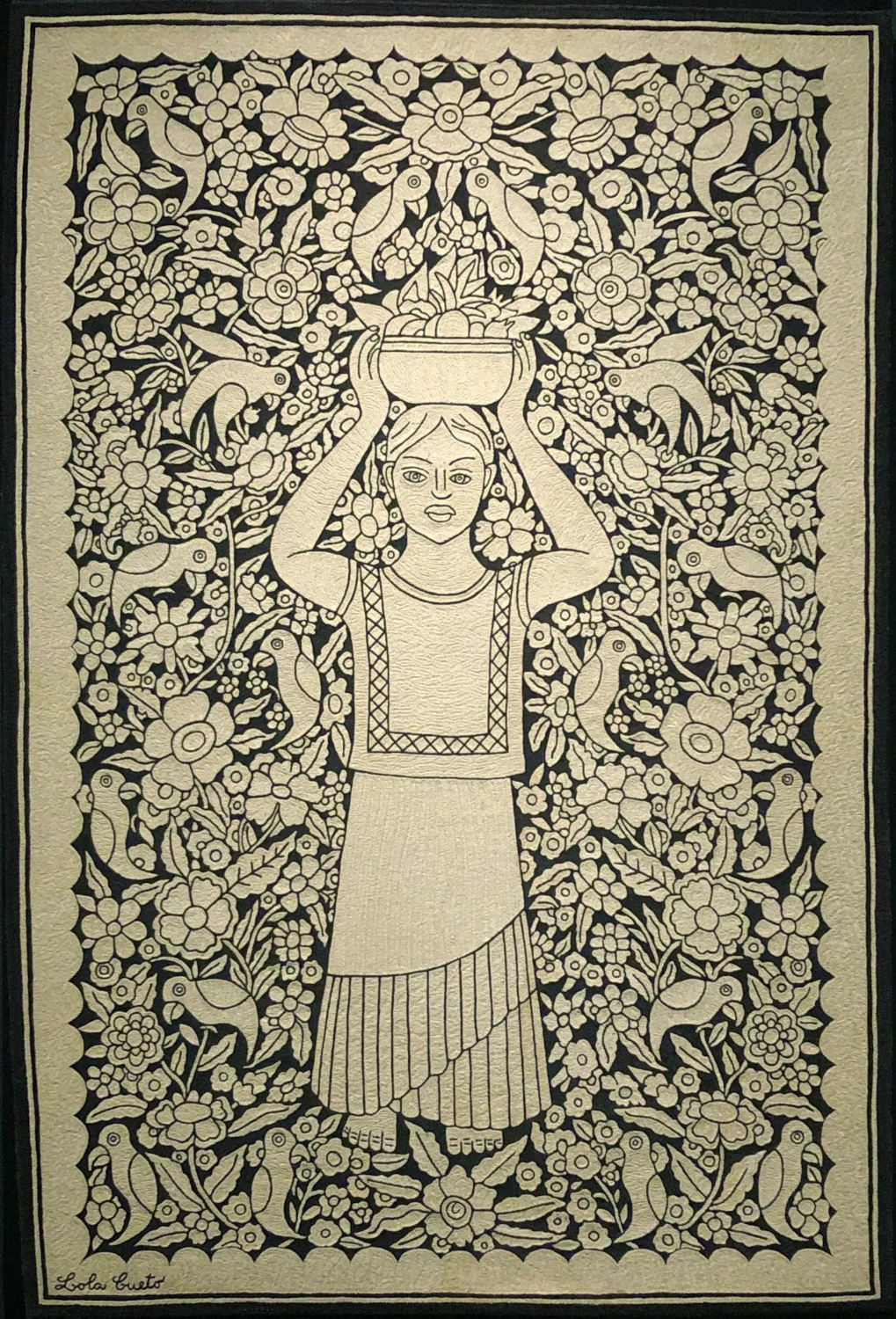

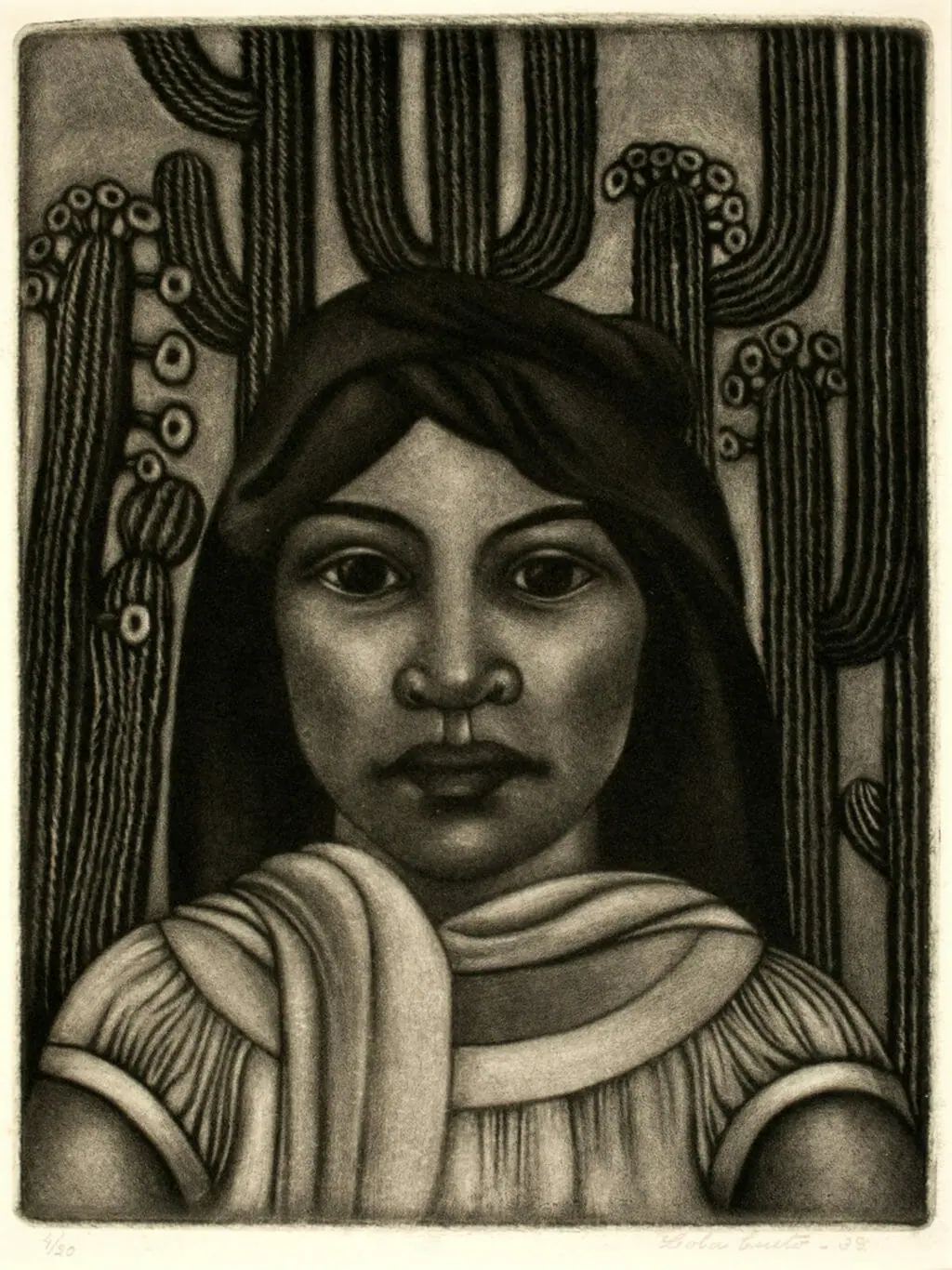

The works Tehuantepec (c. 1920-1927) and Tehuana (1926) exemplify L. Cueto’s approach to embroidery. Here she depicts a Tehuana woman carrying a basket of fruits against a background of flora and fauna that resembles traditional huipil and papel picado designs. A favourite symbol of post-revolutionary artists, L. Cueto captures the characteristic beauty, strength and independence of Tehuantepec women, that had become emblematic of the vitality of indigenous culture in the face of colonisation. She differed from her contemporaries by using embroidery, the medium favoured by many indigenous women, to capture this subject matter; however, she intervened in this traditionally hand-sewn practice by using the newer mechanical technology: a Cornely embroidery machine. L. Cueto’s unique combination of popular arts and modern technology fused past and present, connecting pre-Hispanic indigeneity with post-revolutionary ideologies, and positioning her work as the centre of nationalistic discourses at the time.

She moved to Paris with her husband and two daughters in 1927 and exhibited her textiles with great success. After showing in a major exhibition at Galerie Renaissance in 1929, the critic André Salmon praised her practice, stating “she operates and controls” the machine “as if it were a paintbrush”. L. Cueto’s work appealed to French audience’s obsession with the exotic, and A. Salmon went on to say her tapestries were “the last great hope for those who have tired of African art”.

L. Cueto’s success in Paris led to further exhibitions in Barcelona and Netherlands, but upon returning to Mexico in 1932, she shifted her focus to puppetry. In the following year she, along with her husband, Angelina Beloff (1879-1969), Graciela Amador (1898-1972), Leopoldo Méndez (1902-1969), Roberto Lago (1903-1995) and others, established the puppet theatre known as Rin-Rin. L. Cueto created puppets, directed and performed shows for children in urban and rural areas and also taught a puppet theatre workshop at the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas in 1938. Several puppet theatre groups formed as a result of her work and, with the support of the government, performed across the country for decades. Her daughter, Mireya Cueto (1922-2013), continued her mother’s legacy in her own career in puppetry and by establishing the Museo Nacional del Títere in Huamantla, Tlaxcala.

A notice produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2022