Louise Bourgeois

Bernadac Marie-Laure & Storsve Jonas (ed.), Louise Bourgeois, exh. cat., Centre Pompidou, Paris (5 March–2 June 2008), Paris, Éditions du Centre Pompidou, 2008

→Bernadac Marie-Laure & Obrist Hans Ulrich, Louise Bourgeois: Destruction of the Father, Reconstruction of the Father: Writings and Interviews, 1923–1997, London, Violette, 1998

→Storr Robert & Schwartzman Allan, Louise Bourgeois, London / New York, Phaidon, 2015

Louise Bourgeois, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 3 November–8 Februrary 1983

→Louise Bourgeois, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 5 March–2 June 2008

→Louise Bourgeois. Structures of existence: The Cells, Haus der Kunst, Munich; Garage Museum of contemporary art, Moscow; Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao; Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, 2015–2017

Franco-American sculptor and visual artist.

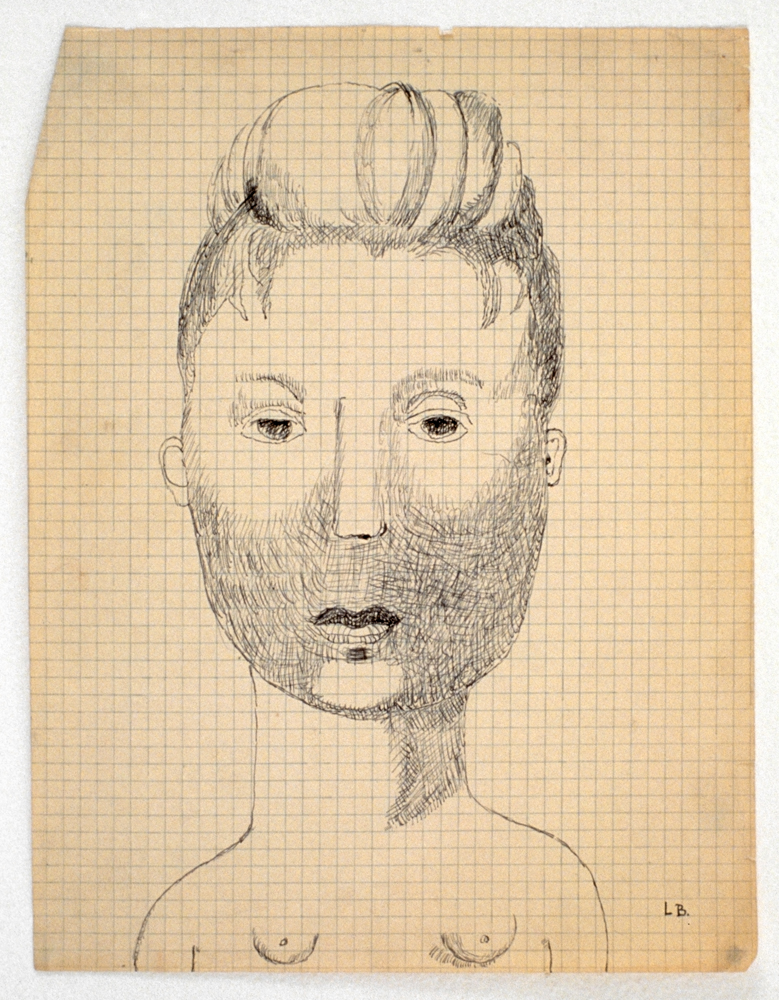

Louise Bourgeois comes from a family of ancient tapestry restorers. After a year in mathematics at the Sorbonne, she had a change of heart and enrolled in the École des beaux-arts de Paris in 1933. Throughout the 1930s, she spent her time in Parisian academies and studios (Ranson, Julian, Colarossi, la Grande Chaumière) and studied under Roger Bissière, Marcel Gromaire, Othon Friesz, André Lhote, and especially Fernand Léger, who advised her to become a sculptor. Cassandre and Paul Colin were also among her teachers. Her rejection from the Surrealist group, especially at the hands of André Breton, had a profound impact on her, and paradoxically, so did the surrealist aesthetic, which would continue to inform her work. In 1938, after her marriage to American art historian Robert Goldwater, she relocated to the United States. In New York, she met the exiled surrealists, such as Miró or Yves Tanguy; she became friends with Nemesio Antúnez, Le Corbusier, Ruthven Todd, Marcel Duchamp. She would continue painting, but use also engraving, achieved many ink drawings and began sculpting. In the early 1950s, she moved on from wood to plaster then to latex, as well as white or black marble, and created shapes resembling seedlings or organs (Fée couturière, Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1963).

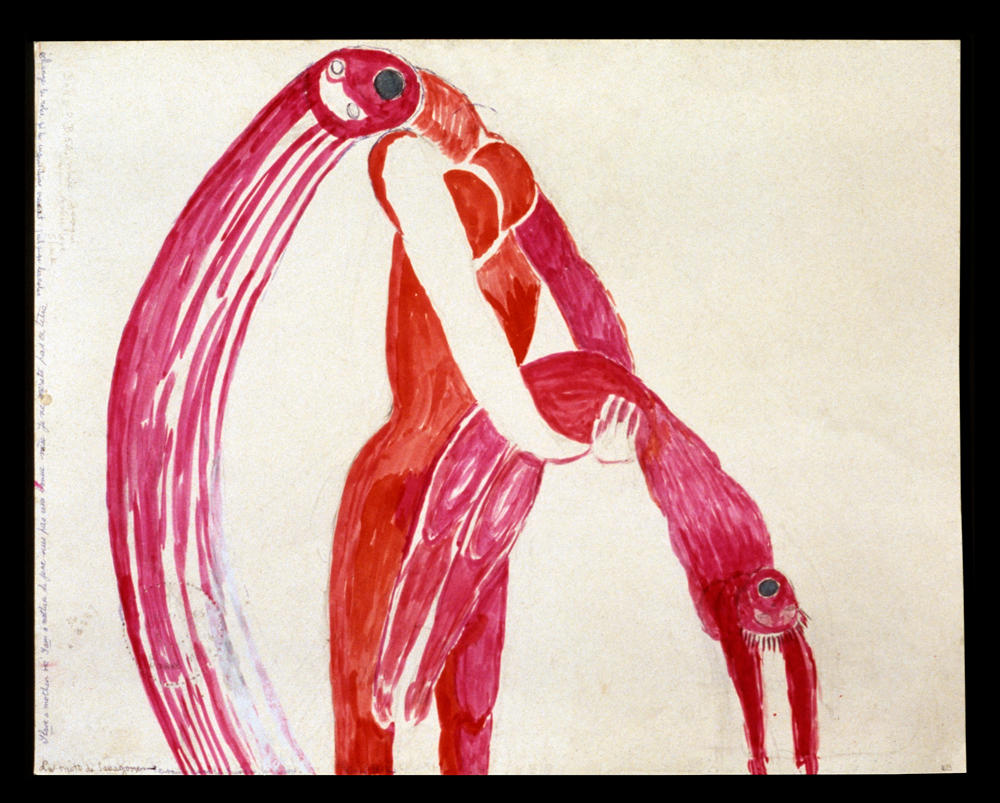

They are intimate explorations of metamorphic, often abstract shapes, sometimes amplified, as can be seen in works like Fillette, a pinkish phallus made out of latex and dangling from a hook (Museum of Modern Art [MoMA], New York, 1968). During the 1970s, she became interested in feminist movements, which dubbed her their “Foremother”; her work, increasingly militant, was highly informed by this companionship (No March, Storm King Art Center, Mountainville, New York, 1972). Following her Nature Studies from the 1980s and 1990s, a great number of her works display an explicitly autobiographical inspiration, including her father’s affair with her nanny, an early family trauma that would leave an important scar. The artist’s late work is equally characterised by a formal proliferation blurring the boundaries between installation and sculpture as by increasingly clear references to this harrowing childhood. The Extrême tension series (lead pencil and watercolour on paper, 2007), now part of the collections of the Centre Pompidou in Paris, bears the traces of the fragmentary perception of the body and the emotions and sufferings that belong to it.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Louise Bourgeois : « I Transform Hate Into Love »

Louise Bourgeois : « I Transform Hate Into Love »