Lucie Cousturier

De Lanfranchi Adèle, Lucie Cousturier, 1876-1925, Paris, A. de Lanfranchi, 2008

→Kerzerho Gilles (ed.), Lucie Cousturier : de Signac à Bakoré Bili, exh. cat., lieu-dit Chapelle du Calvaire, Rousset (7–31 October 2014), Rousset, Association Index, 2014

Lucie Cousturier, Galerie Duret, Paris, 16–31 January 1907

→Lucie Cousturier: de Signac à Bakoré Bili, lieu-dit Chapelle du Calvaire, Rousset, 7–31 October 2014

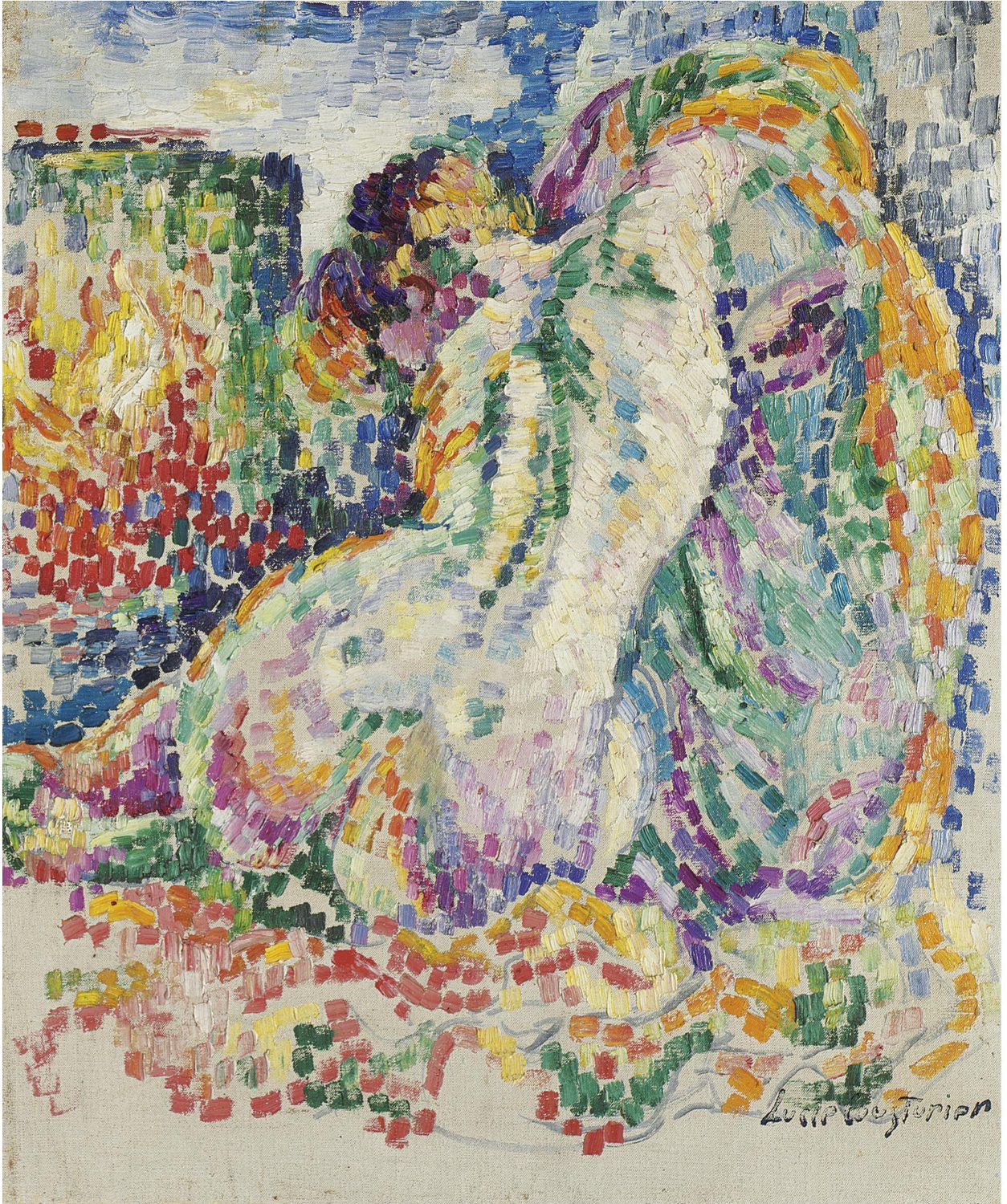

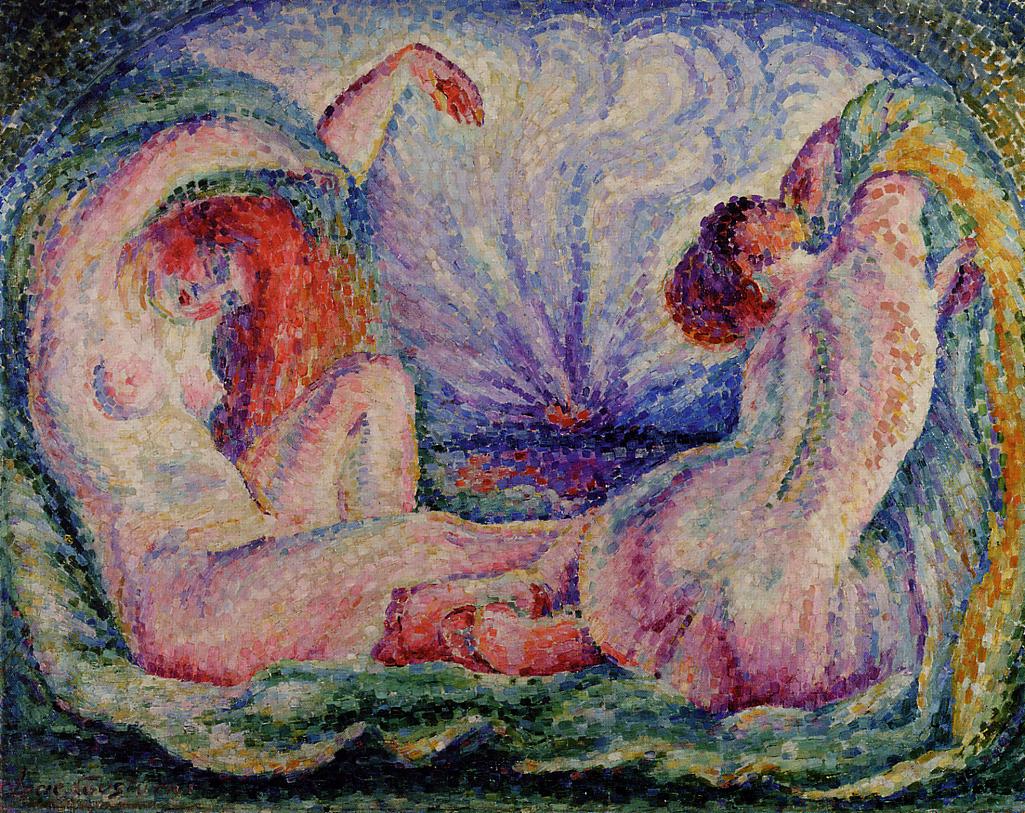

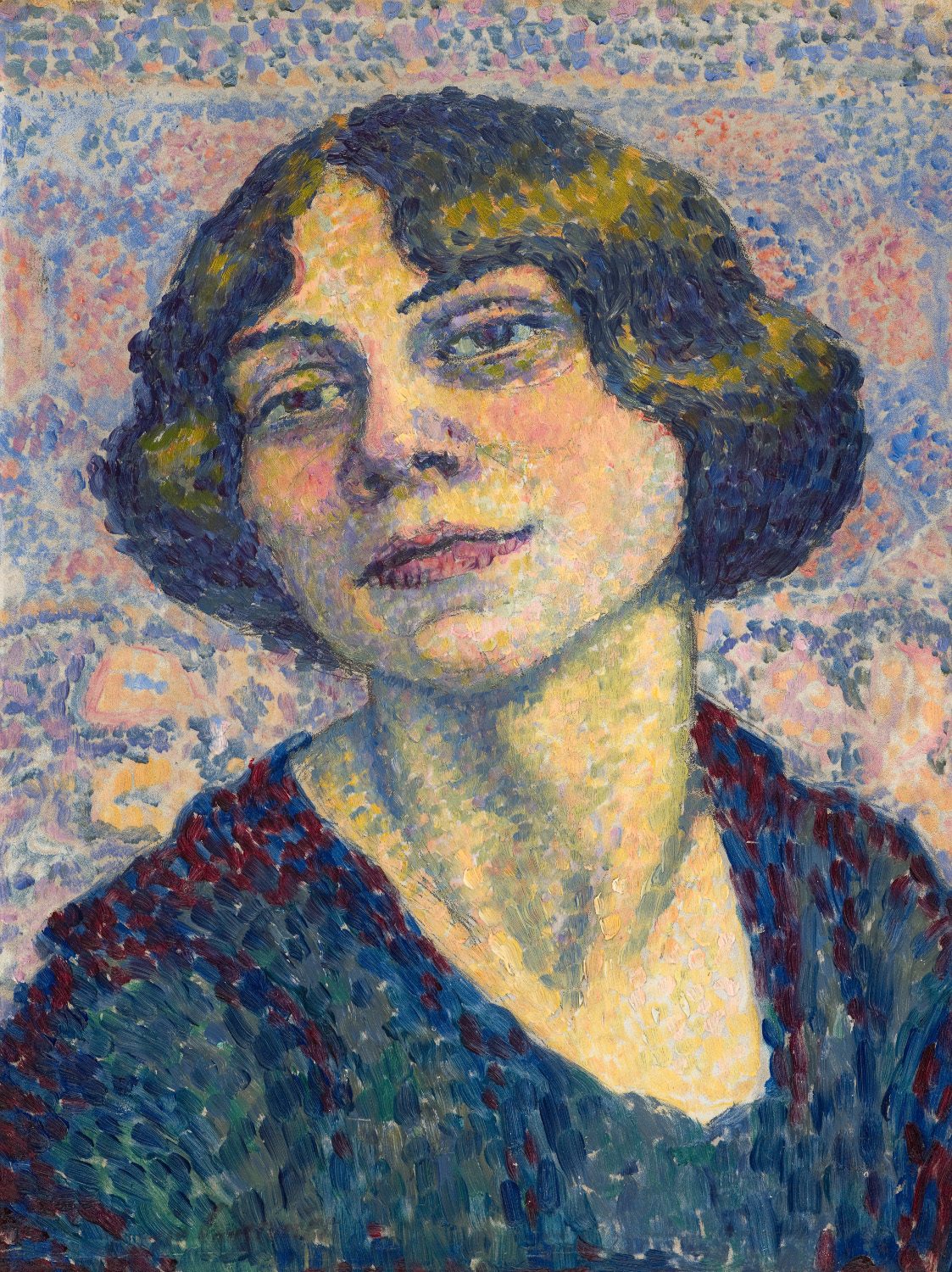

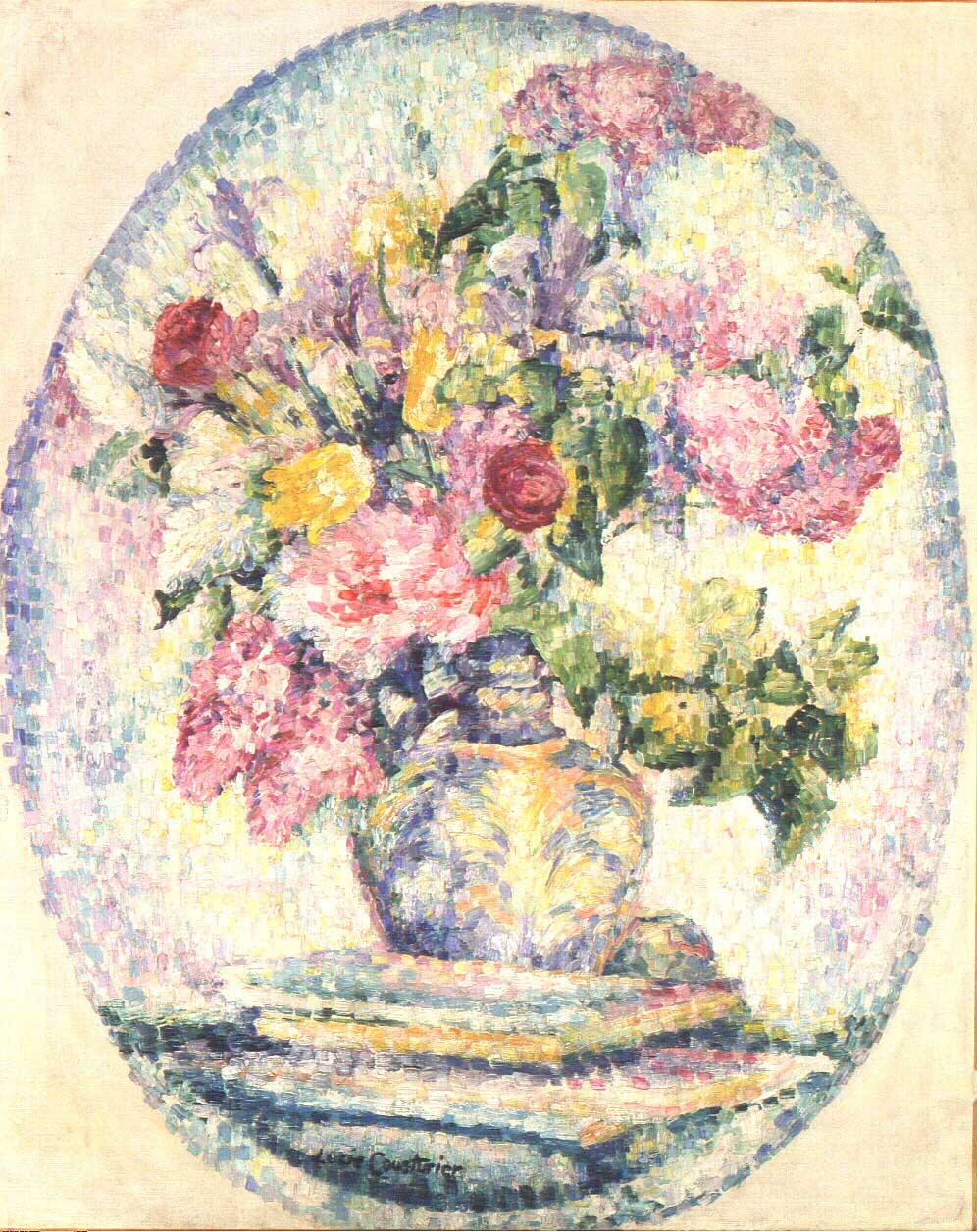

French painter, art critic, and anticolonialist militant.

Born to a wealthy and innovative family – her parents manufactured the first rubber dolls –, Lucie Brû was a nonconformist. In 1900 she married the writer Edmond Cousturier, with whom she had a son in 1901, the year in which she first presented her work at the Salon des indépendants in Paris. In 1906 she showed her work at the Salon de la libre esthétique in Brussels, and a few paintings at the Berliner Secession in Berlin. Her first solo show was held in Paris at the Eugène Druet Gallery in 1907. A pointillist painter, Cousturier had a predilection for landscapes, outdoor painting and, of course, the luminous quality of Southern France. As from 1911, she also started writing articles and monographs on the major members of Neo-Impressionism, making her the first specialist of the movement. In 1916, while the couple stayed in Fréjus during the war, the artist taught Senegalese Tirailleurs from the neighbouring camp to read and write. Transformed by this encounter, she engaged in an anticolonialist reflection and, after the war, published autobiographical stories, in particular Des inconnus chez moi [Unknown persons at home] (1920).

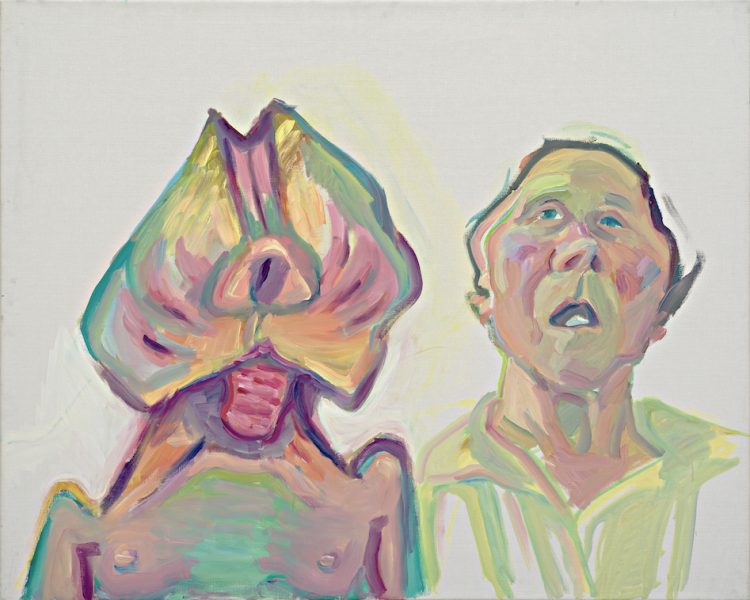

She was commissioned to study “the indigenous family circle, and specifically the role of women”, and to this end embarked on a ten-month journey to West Africa (1921); the articles she published in the magazine Paria testify to her political beliefs. Her vision of the African people contrasted sharply with the exotic representation that many fashionable colonial artists had of it at the time: her drawings and colour washings depicted differentiated individuals rather than African archetypes. On the occasion of the reopening of his gallery in Brussels in 1923, Georges Giroux held an exhibition of Paul Signac and Cousturier’s works, with watercolours and drawings of her travel. Her health declined, and she died in June 1925. Her writing and work on her African friends has now become a subject of research.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017