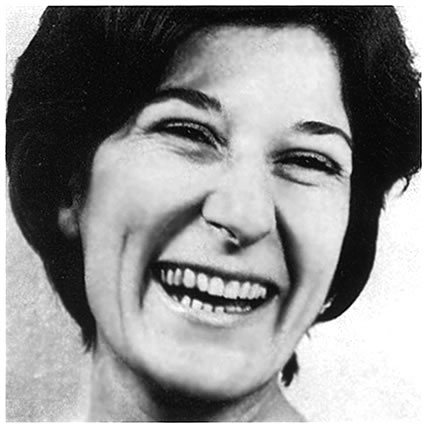

Lucie ‘Ti’iwan’ Couchili

Amazonies, Lyon, 18 April 2025 – 8 February 2026

→Injustices environnementales – Alternatives autochtones, Genève, 24 September 2021 – 21 August 2022

→Imprégnation animale, Fort-de-France, 2017

French Guianese artist.

Lucie ‘Ti’iwan’ Couchili was born in Saut Tampok, a small village that no longer exists, in French Guiana’s southwestern municipality of Maripasoula. She was raised in a family clan belonging to the Teko, Wayana and Wayãpi indigenous nations. At the age of eight, she was sent to an ‘Indian home’, the Guianese equivalent of a Catholic boarding school, whose aim was to ‘civilise’ the native peoples of the Amazon forest. Three years later, no longer able to bear the loss of her freedom or the harsh collective punishment meted out at this school, she ran away.

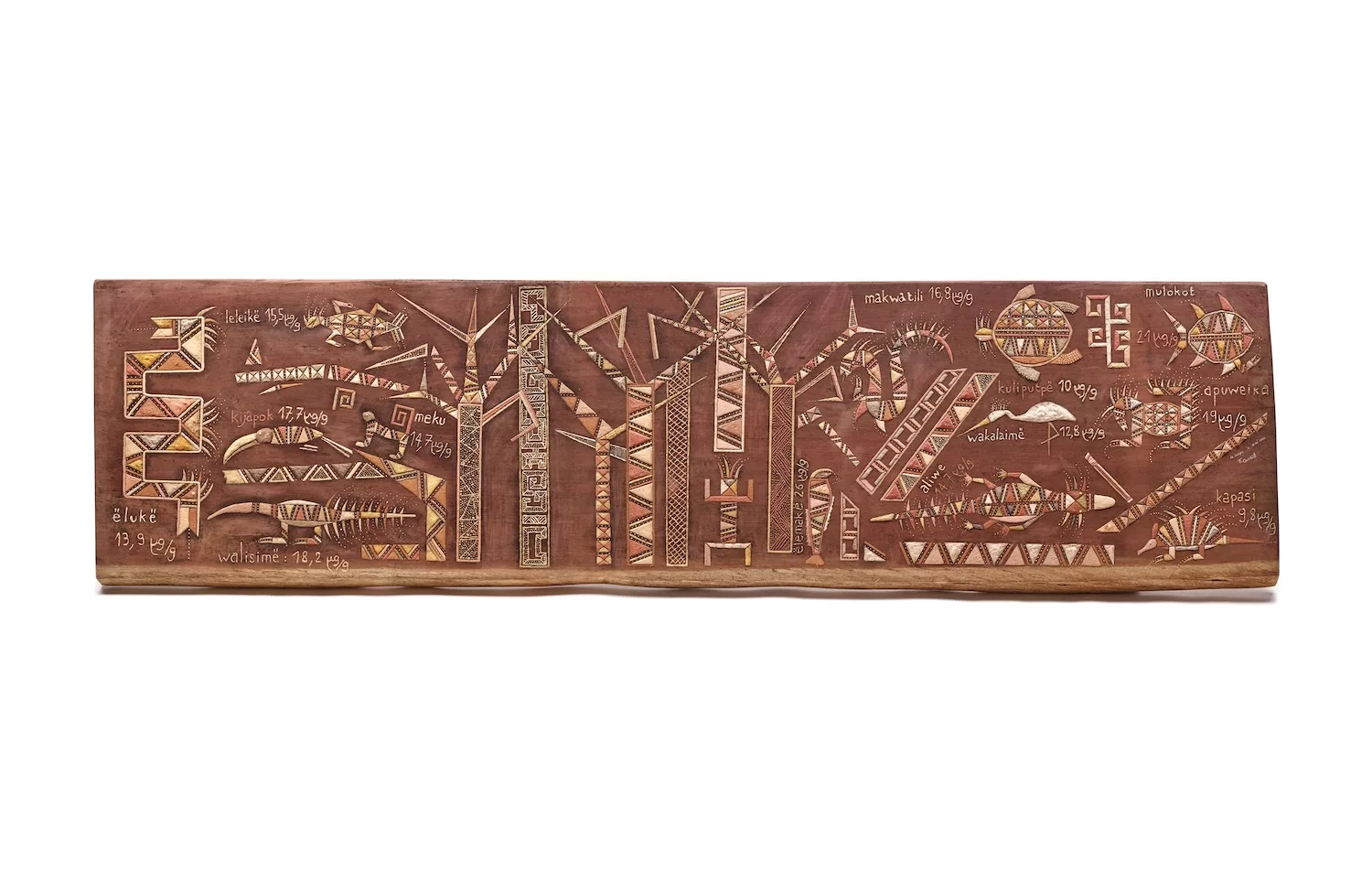

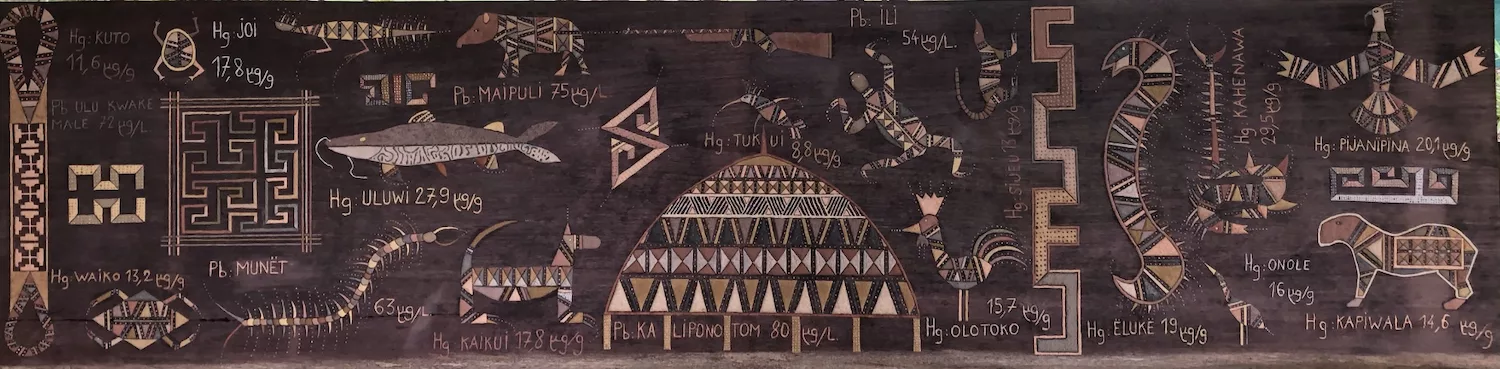

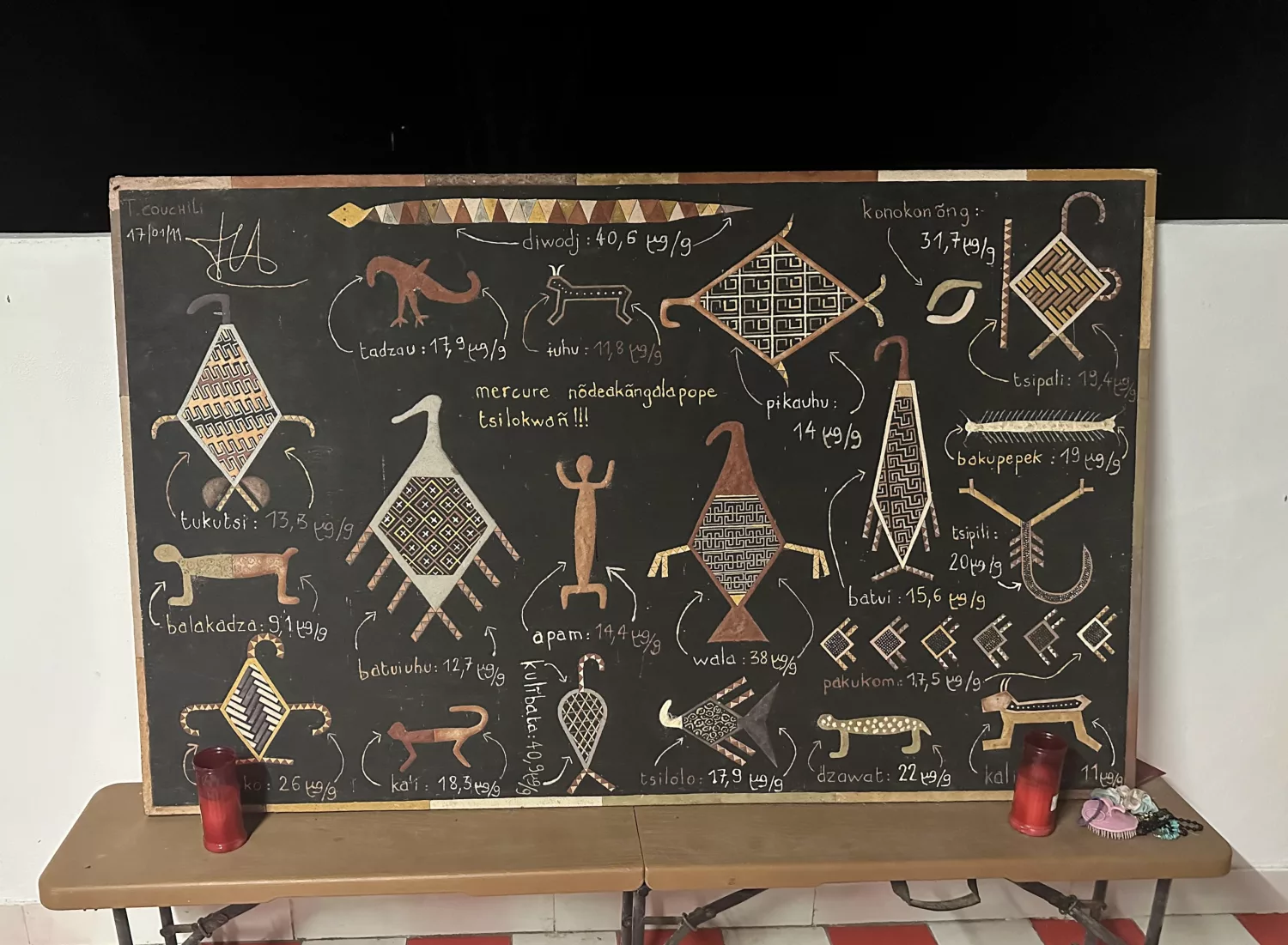

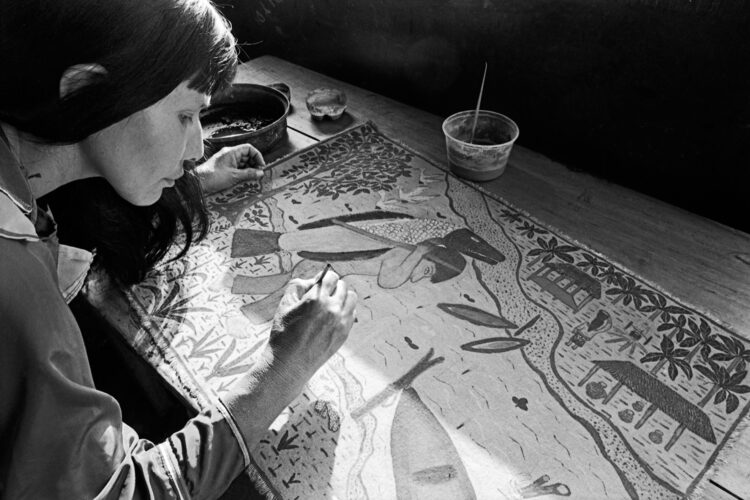

Traditional stories told by Teko and Wayana elders were a formative part of her early years. Kulawaliku – her uncle Palipen’s mother and Chief Masili’s widow – introduced her to the lore of the maluwana or ‘house sky’. Although in principle women are not allowed to make these painted wooden discs that Amerindian villagers hang from the ceilings of their tukusipan, or communal houses, as protection from unseen spirits, she made her first maluwana in 1990. In 1998, she turned away from oil-based paints, preferring instead to revive an age-old but neglected Wayana technique that involves mineral pigments. Then, in 2000, she entered an arts and crafts competition organised by French Guiana’s Chamber of Skilled Trades and won first prize in the ‘ritual objects’ category.

Ti’iwan Couchili has transformed her culture’s traditional bestiary by incorporating new animals, resurrecting old styles and using techniques and symbols borrowed from other art forms, such as face and body painting, basketry, beadwork and pottery. Her work is informed by all these visual vocabularies and shows that they can coexist harmoniously when transposed onto a common space. Her conceptual journey and aesthetic perspective are documented in the Danish anthropologist Perle Møhl’s 2004 book Omens and Effect: Divergent Perspectives on Emerillon Time, Space and Existence.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the death of her maternal grandmother – caught in a shootout involving illegal gold miners – and a string of suicides in her family (an uncle, an aunt and several cousins, nephews and nieces) had a profound impact on her creative momentum. Using the same materials as for her house skies (various laterites and coloured clays), she chose to dedicate a portion of her work to exposing the social and environmental hardships affecting French Guiana’s native communities: suicides, substance addictions, land theft, water contamination, deforestation and the absorption of toxic heavy metals (mercury and lead) by both animals and people. While these politically engaged works are generally painted-wood pieces, like the house sky, they break free from the blackened disc’s geometric constraints, reflecting the liberties the artist has taken but still connected to the rich graphic repertoire of traditional art forms. She includes writing in Amerindian languages, now a hallmark of her style, in nearly all her pieces. “When the indigenous peoples of French Guiana saw Europeans writing, they immediately recognised the semiotic significance of the practice and related it to their own traditions,” she explains. ”In our languages, we have a single word for the actions of painting traditional motifs and writing.” This facet of her work has earned her invitations to show her art in several international exhibitions: Imprégnation animale (Fort-de-France, 2017), Injustices environnementales – Alternatives autochtones (Geneva, 2021) and Amazonies (Lyon, 2025).

Ti’iwan Couchili - Nommée au prix Nouveau Regard 2025 | AWARE, 2025

Ti’iwan Couchili - Nommée au prix Nouveau Regard 2025 | AWARE, 2025