Prix AWARE

Portrait of Ti’iwan Couchili near her atelier, December 2014 © Paul-Aimé William

Painter Ti’iwan Couchili was raised in a family with roots in three of Guyana’s indigenous nations: Teko, Wayana and Wayãpi. Her childhood was enriched by the stories told by the elders, from whom she learned the traditional techniques of maluwana1.

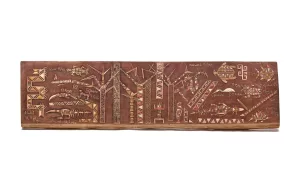

Ti’iwan Couchili, Maluwana, undated, © Ti’iwan Couchili

Ti’iwan Couchili, Maluwana, undated, © Ti’iwan Couchili

For over three decades, she has been practising this art form, which traditionally begins with a wooden disc on which non-human mythical figures are depicted, painted to match the spherical shape of the support. The maluwana is then hung from the ceiling of a tukusipan – a circular carbet (wooden living structure) with a community function – to decorate this dwelling and protect it from evil influences. For a long time, this practice was carried out exclusively by older men: in this gendered division of creation, women were forbidden to make maluwana. They were therefore deprived of learning and using this living piece of culture, just like children. The patriarchal regime justified this exclusion by citing numerous physical dangers, and even the risk of death in the event of transgression.

Ti’iwan Couchili’s visual art is consistently constructed around “traditional graphic identities”2. She reinterprets customary bestiaries derived from a variety of media – basketry, beadwork, facial and body painting, pottery – by inscribing them in a “creative modernity”. The artist defends her works as paintings in their own right, despite the stereotypes that reduce her to a self-taught artist creating crafts rather than legitimate art. In her practice, she constantly challenges the norms of contemporary painting, situated between hegemony and supremacy, which marginalise local creations, training and knowledge outside the world of white art. Through an approach involving repetition and variation, Ti’iwan Couchili reorganises the visible space immanent to the terrestrial and aquatic beings of Maluwana, associating new physicalities and powerful cognitive fields that raise questions both internal and external to her community.

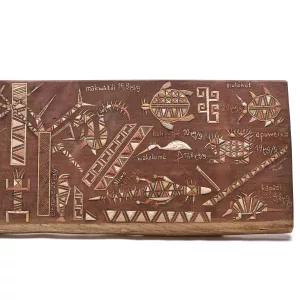

Ti’iwan Couchili, Tintukai, (Deforestation), undated, © Ti’iwan Couchili

Ti’iwan Couchili, Tintukai, (Deforestation), detail, undated, © Ti’iwan Couchili

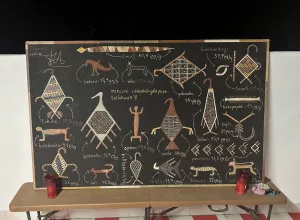

Ti’iwan Couchili, Imprégnation mercurielle, 2011, © Paul-Aimé William

For the past fifteen years, part of her work has focused on the social and ecological disorders endured by Guyana’s indigenous communities: suicides, addictions, land dispossession, water pollution, deforestation, and the contamination of human and non-human beings by heavy metals. In Imprégnation mercurielle and Tintukai [Deforestation], the animal motifs are each accompanied by a descriptive text composed of the indigenous name of the being depicted and its mercury level in micrograms per gram. These works reflect the environmental contamination with mercury that has occurred in French Guiana since the 1990s as a result of historical gold mining and illegal gold panning. Ti’iwan Couchili also warns of the lack of prevention with regard to this toxic metal in its primary state in the region’s ecosystem, which is excessively absorbed, particularly by the indigenous population. Her works, which politicise the continuity of the material and the spiritual, have been exhibited outside French Guiana at the Tropiques Atrium in Martinique, the Musée des Confluences in Lyon and the Musée d’Ethnographie in Geneva.

Paul-Aimé William

Ti’iwan Couchili belongs to the Teko people of Amazonia (sometimes referred to as Emérillons by Westerners). She was born in 1972 in the village of Saut Tampok on the Alawa (Tampok) River, about two hours by pirogue from its junction with the Maroni River. Her family lives in Kayodé, Elahé, and Camopi. Ti’iwan Couchili is an Indigenous artist from the Teko Nation of French Guiana. She now lives and works in the commune of Montsinéry.

The Maluwana or Maluana is a traditional architectural element of the Wayana and Apalais peoples, found in French Guiana, Suriname and Brazil. It consists of a disc made of cheese tree wood placed at the top of the vault of the tukusipan, a large domed collective hut usually erected in the centre of villages.

2

Correspondence with the author, December 2024

Tous droits réservés dans tous pays/All rights reserved for all countries.