María Blanchard

Caffin-Madaule Liliane, María Blanchard, 1881–1932, Catalogue Raisonné: Spain’s Greatest 20th-Century Female Painter: Spain’s Greatest Cubist Female Painter, London, Éditions Liliane Caffin Madaule, 1992-2007

→Bernardez Sanchis Carmen, María Blanchard, Madrid, Fundación MAPFRE, Instituto de Cultura, 2009

→Salazar María José (ed.), María Blanchard, exh. cat., Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, (17 October–25 February 2013), Madrid, Fundación Botín : Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2012

María Blanchard. Cubist, Fondation Marcelino Botín, Santader, 23 June–16 September 2012

→María Blanchard, Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid, 17 October–25 February 2013

Spanish painter.

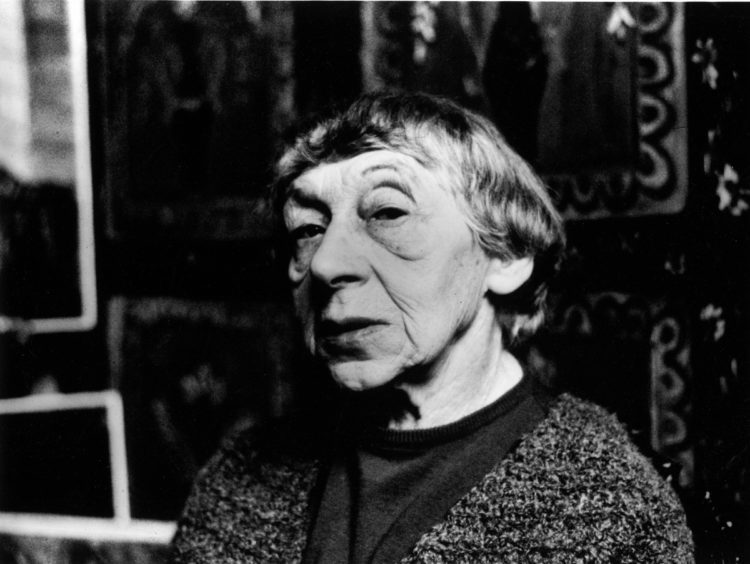

Born to a cultivated middle-class family from Santander, Franco-Polish on her mother’s side and Spanish on her father’s, María Gutiérrez-Cueto y Blanchard suffered from dwarfism and physical deformity. Encouraged by her relatives, she moved to Madrid to study under the best painters: Emilio Sala, Fernando Álvarez de Sotomayor, then Manuel Benedito – champions of academism with a slight hint of modernity. In 1909, she took advantage of a scholarship granted by her hometown to move to Paris, where she led a precarious and laborious life. She studied painting under the Spanish painter Anglada Camarasa and with Kees van Dongen at the Vitti Academy, then enrolled in the Vassilieff Academy. During this time, she was rewarded at the National Fine Arts Shows in Madrid in 1909 and 1910.

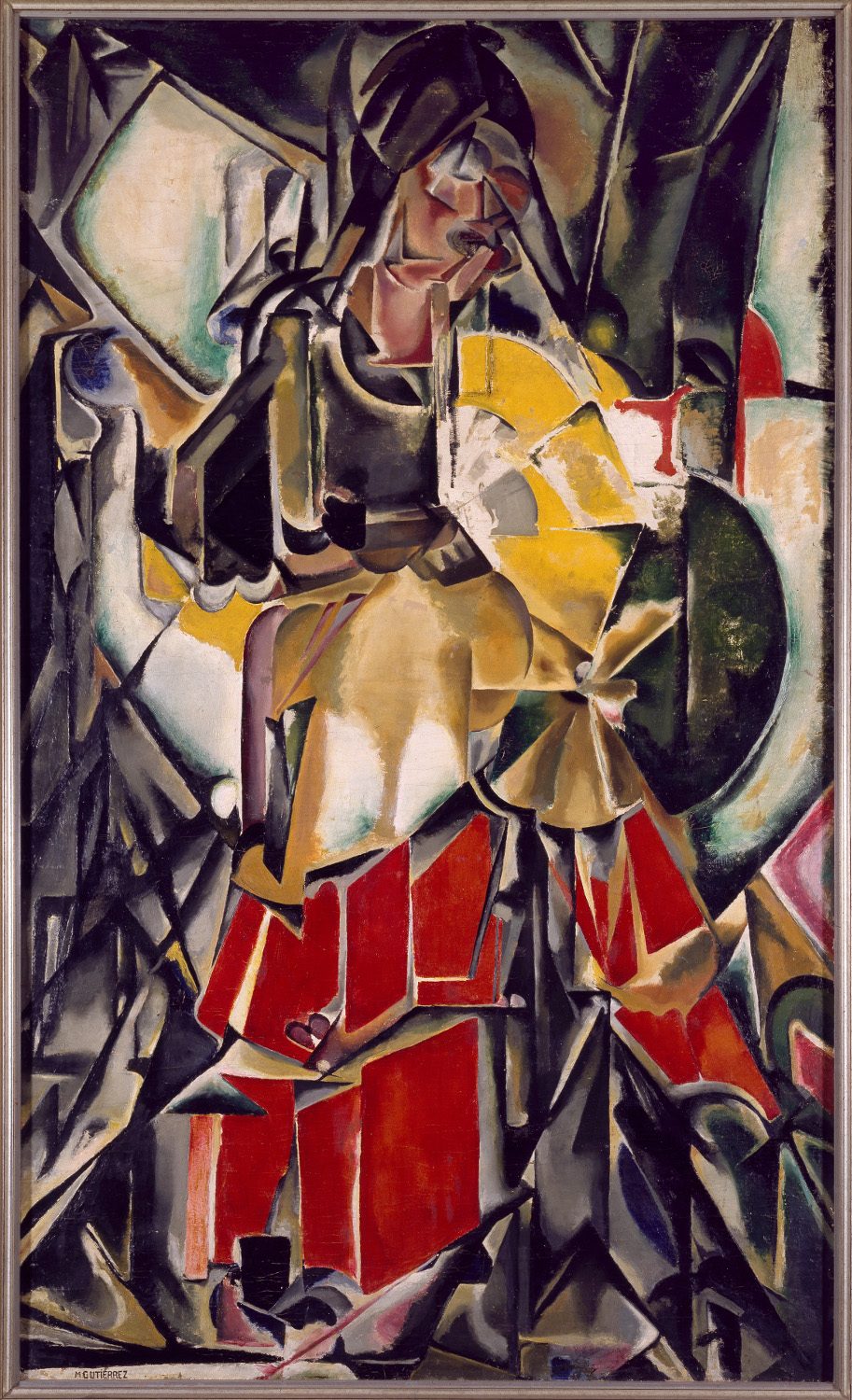

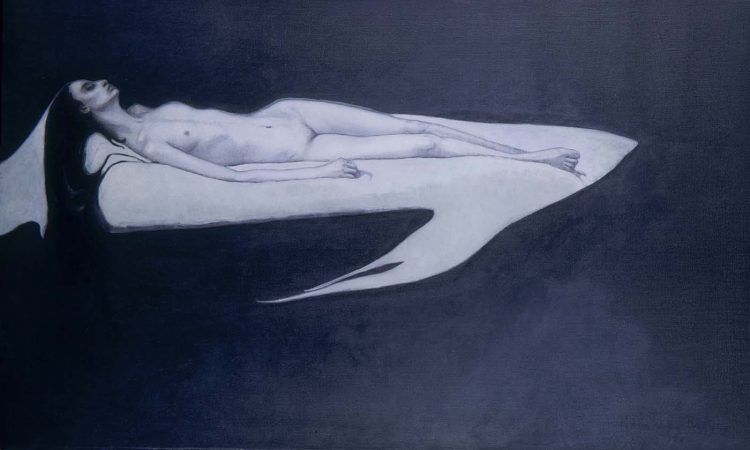

She returned to Spain in 1913, took part in the exhibition Pintores íntegros [“Unbiased painters”] and was given a chair teaching drawing in Salamanca; but aggravations and incomprehension led her to move back to Paris in 1916. During this second stay in Paris, she first painted purely cubist still lives. She was one of the protégées of the gallerist Rosenberg and befriended avant-garde painters such as Juan Gris and André Lhote. Her Communicant caused a sensation at the Salon des Indépendants in 1921 for its ingenuity and expressionist ferociousness. She then proceeded to “return her work to order”, with a more figurative style tinged with cubist reminiscences in her portraits of children and mothers, which were often reproduced in several versions. Her solitary physiognomies make her language easily identifiable. Juan Gris’ death in 1927 deeply affected her, leading her to depression, for which she sought solace in devout religiosity. One of her last works, San Tarcicio, would become the inspiration for a Paul Claudel poem.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017

Interview with María José Salazar, exhibition María Blanchard, Museo Reina Sofía

Interview with María José Salazar, exhibition María Blanchard, Museo Reina Sofía  Interview with María José Salazar, curator of the exhibition María Blanchard, Cubista. Fundación Botín

Interview with María José Salazar, curator of the exhibition María Blanchard, Cubista. Fundación Botín