Marie-Louise Lefèvre-Deumier

Pauline Minali, Profession sculptrice. Performance et transgression de genre sous le Second Empire, Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, “Archives du féminisme”, 2020

→Anne Rivière (dir.), “Lefèvre-Deumier Marie-Louise”, Dictionnaire des sculptrices en France, Paris, Mare & Martin, 2017, p. 316–17

→Marjan Sterckx, Roulleaux Dugage, Azalaïs Marie-Louise (1812-1877), Digitaal Vrouwenlexicon van Nerderland

→Marjan Sterckx, “The Invisible “Sculpteuse”: Sculptures by Women in the Nineteenth-century Urban Public Space – London, Paris, Brussels”, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, vol. 7, no. 2, Autumn 2008

Sculpture’Elles. Les sculpteurs femmes du XVIIIe siècle à nos jours, Musée des Années 30, Boulogne-Billancourt, 12 May–2 October 2011, exh. cat. p. 122–123

→L’Art en France sous le Second Empire, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, 1 October–26 November 1978, Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, 18 January–18 March 1979, Grand Palais, Paris, 11 May–13 August 1979, exh. cat. p. 978–9, cat. 155

French sculptor and journalist.

Azalaïs Marie-Louise Roulleaux-Dugage was born into a wealthy bourgeois family, the daughter of Jacques François Nicolas Roulleaux-Dugage, lawyer and sub-prefect of Argentan (Orne), and Adélaïde Victoire Bertrand L’Hodiesnière. She married Jules Lefèvre, writer and poet, on 4 February 1836, and the couple had two sons: Maxime and Eusèbe. When in 1842 her husband received his inheritance from an aunt Deumier, he added her surname to his, and from then on Marie-Louise went by Lefèvre-Deumier. The couple settled in a hôtel particulier on the Place Saint-Georges in Paris, and also had a property in the vicinity of the Abbaye Notre-Dame du Val near Pontoise. M.-L. Lefèvre-Deumier held salons alongside her husband, where they received the most fashionable romantic writers of the day, including Alfred de Vigny, Honoré de Balzac, Alphonse de Lamartine and the Dumas father and son. The couple also financially supported the revue L’Artiste. J. Lefèvre-Deumier had publicly endorsed Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, and was named Librarian of the Élysée Palace when the latter became President of the Republic. The proclamation of the Second Empire in 1852 affirmed the couple’s social standing, a situation which no doubt benefitted M.-L. Lefèvre-Deumier who now embarked on her career as a sculptor.

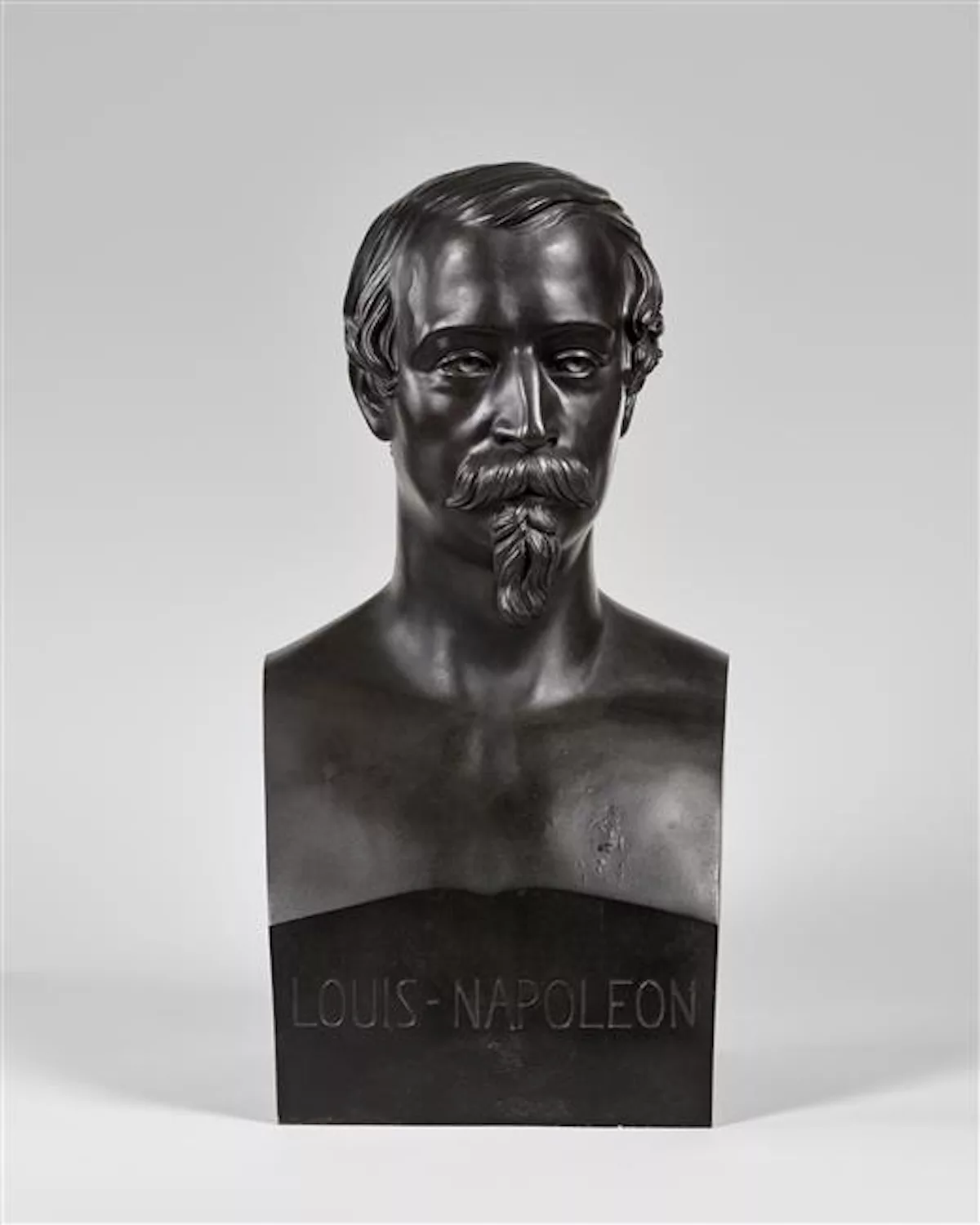

Little information has survived regarding M.-L. Lefèvre-Deumier’s artistic education, and we do not know who trained her in her craft. Her first foray was, rather impressively, the Salon of 1850, where she was the only woman sculptor to participate. The two works, the bust of a woman and a full-length figure of a Jeunepâtre de l’île de Procida [Young Shepherd of the Isle of Procida, Caen, Musée des Beaux-Arts, presumed destroyed by bombing in 1944], did not go unnoticed by critics. At the Salon of 1852 she exhibited a marble bust of the Prince-Président, from which the Ministry of the Interior commissioned a run of fifty bronze copies. The bust, available in both antique and uniform finishes, was also proposed to departments for purchase by subscription through the Maison Barbedienne, with the choice of stearinised or unstearinised plaster, bronze-coated zinc or marble.

M.-L. Lefèvre-Deumier’s official career took off with her creation of the first official bust of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte. In 1853 she finished Souvenir de Notre-Dame, a statuette showing Empress Eugénie kneeling at her prie-dieu on her wedding day. She also made a bust of the empress of which several examples are known. At that year’s Salon, she was awarded a third-class medal for her marble busts (unlocated) of her son Maxime and Monseigneur Sibour, the archbishop of Paris. Two years later, in 1855, she received an honourable mention at Paris’ Exposition Universelle. Celebrated by her contemporaries for her talents as a portraitist, she also portrayed mythological and allegorical figures. In 1856 she created the model for La Nymphe Glycère (also known as La Couronne de fleurs), which would be installed in the square courtyard of the Louvre in 1861 – she was, along with Claude Vignon (1828–1888) and Hélène Bertaux (1825–1909), one of the rare woman sculptors to receive a commission for the decor of the new Louvre. At the Salon of 1863, she exposed L’Étoile du matin (Rouen, Musée des Beaux-Arts). She also wrote for a number of journals under the pseudonym Jean de Sologne.

Following her husband’s death in 1857 M.-L. Lefèvre-Deumier faced financial difficulties and began to receive an annual pension of 2,000 francs from the government. She also actively sought out commissions. She applied for the post of “sculptor of the Empress’ household” but was rejected. She did, however, receive orders for busts of Lieutenant General Henri-Joseph Paixhans (1859) and Brigadier General Benoît Sibuet (1868) for the historical galleries at Versailles, and the administration bought one of her early works, a bust of Alphonse de Lamartine (1852). She worked in The Hague in 1863 and 1864, sculpting busts of members of the Dutch royal family. At the fall of the Empire in 1870, she ceased to exhibit works. She died in 1877. In that year, a statue in plaster was posthumously presented at the Salon: Hommage funèbre, destined for her own family tomb.

A biography produced in partnership with the Louvre Museum.

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2025