Marisa Merz

Celant, Germano (ed.), Marisa Merz, exh. cat., Musée National d’Art Moderne – Centre Pompidou, Paris, (15 February–2 May 1994), Paris, Centre Georges-Pompidou, 1994

→Fondazione Merz (ed.), Marisa Merz, Turin, Fondazione Merz, 2012

Marisa Merz, Musée National d’Art Moderne – Centre Pompidou, Paris, 15 February–2 May 1994

→Marisa Merz, Centre International d’Art et du Paysage de l’Île de Vassivière, 15 July–31 Otoctober 2010

→Marisa Merz: The Sky Is a Great Space, The Met Breuer, New York, 24 January–7 May 2017

Italian sculptress and mixed media artist.

Before dedicating herself entirely to graphic arts, Marisa Merz studied architecture, during which time she met her husband, Mario Merz, a major artist of the Italian art scene of the second half of the 20th century. She began showing her work in 1967 in Turin, birthplace of Fiat and of the protest movement Arte Povera (“poor art”). The movement, which brought together a group of Italian artists as from the late 60s, used “poor” materials, often taken from everyday life, as art objects. In 1968 Marisa Merz, her husband, Jannis Kounellis and Michelangelo Pistoletto, among others, participated in the event Arte povera + Azioni povere (“poor art + poor actions”). On this occasion, she made braided copper and nylon thread pieces shaped like small children’s shoes (Scarpette di Bea) or in the likeness of her daughter Beatrice and left them on the beach in Amalfi. Since her beginnings, metal was always her material of choice in her figurative and abstract work alike. This material was typical of Arte povera artists but also of the New York disciples of Minimal Art – a movement she distinguished herself from in the way she worked materials and created new shapes, delicately assembling aluminium sheets, weaving inextricable nylon and copper webs, subjecting these industrial materials to the patient labour of sewing traditionally attributed to women, making them light, airy, and insubstantial like cobwebs (Untitled, 1979), organic in their tubular or triangular shapes and in the slightly irregular excrescence they always present. The artist’s attention to the intrinsic properties of materials and value she places in their rigidity or flexibility, their malleability, and especially their colour, are essential elements of her universe – poetic, uncluttered, and undeniably driven by a search for beauty.

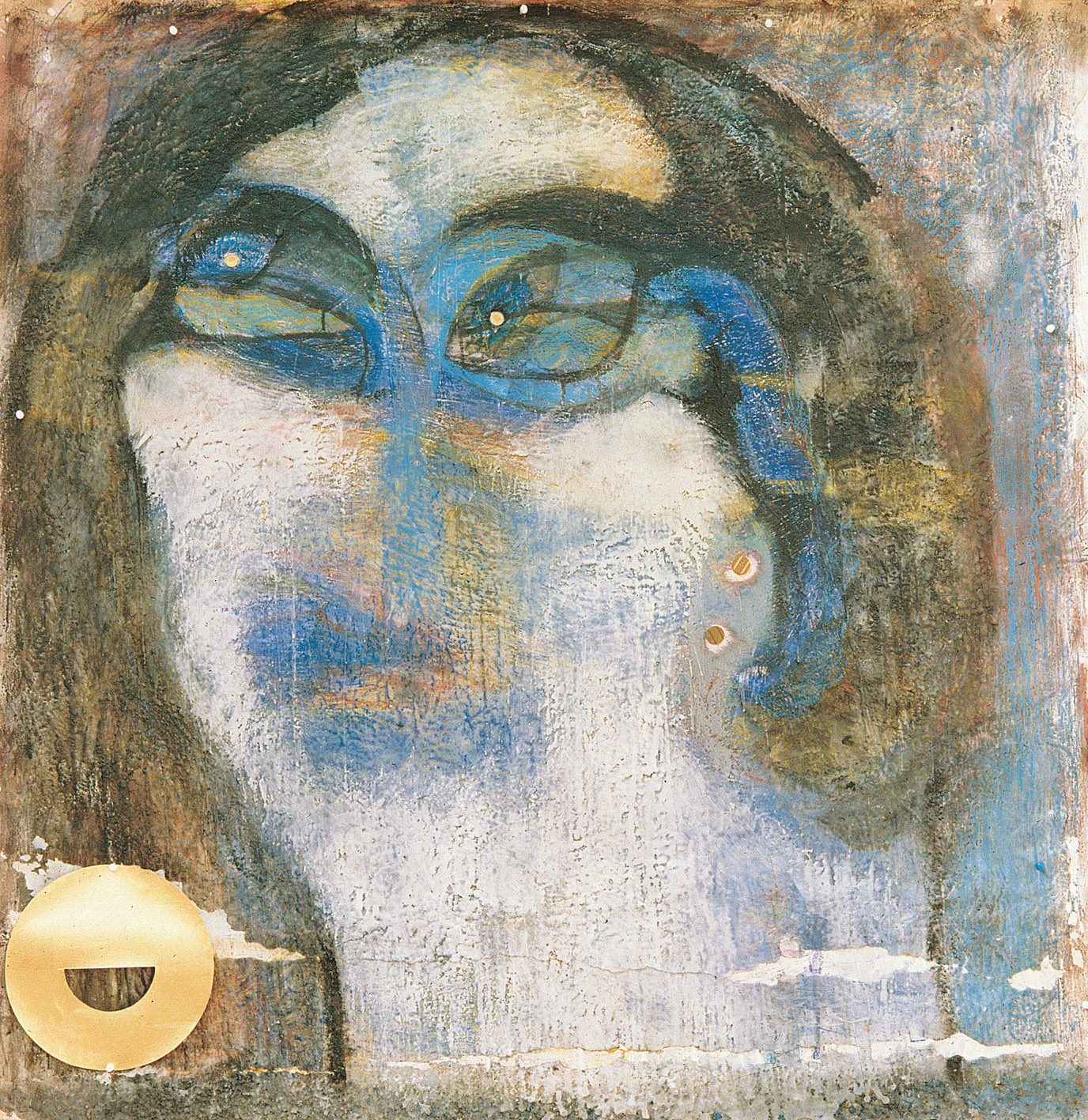

In the 1970s she started working with wax and paraffin, giving shape to these usually shapeless substances. Copper is also very present in her work, whether in its material or warm-coloured form, and has almost become the artist’s leitmotiv. This play on shapes and materials reaches its full expression in her installations, which merge seemingly scattered and dissimilar objects as if in a dream: cups and threads, glasses, tables, rose petals, leaves, or a bathtub where plant-like steel excrescences grow alongside an isolated block of paraffin. Her installations, which often remain untitled, question the unity of the work of art. They do not make for easy interpretation, but rather conjure up the viewer’s imagination, like an invitation into an intimate world made even more lyrical as the artist became in the habit of supplementing them with her own poems as from 1979. Our imagination is particularly stimulated by a combination of sensory suggestions; for example, the 1997 piece Untitled features a violin-shaped white wax fountain placed in a dark leaden receptacle, which receives the trickling sounds of the water jet as it spouts from the violin. As from the 80s the human figure, whether drawn or modelled, began to take up a considerable part of her installations. She drew an extensive series of portraits on canvas and paper, in pencil or pastel, in small or very large formats. She also began a series of plaster and clay modelled heads, and experimented with all sorts of shapes, eventually obliterating the features altogether by pouring green wax onto the heads, in an approach remotely reminiscent of Medardo Rosso’s sculpture. Often coloured (Untitled, multi-coloured clay, 1982) and sometimes covered with thin copper or gold mesh, her modelled heads are placed on suggestions of pedestals (stools, tripods, chairs), as are her painted heads and most of her objects, thus adding complexity to the scenography of her installations. In spite of the artist’s discretion, many prestigious institutions – Venice Biennale, Rome Quadrennial, Centre Pompidou – have paid tribute to her work.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2017