Mira Schendel

Marques Maria Eduarda, Mira Schendel, São Paulo, Cosac & Naify Edições, 2001

Mira Schendel, Tate Modern, London ; Museu de Arte Contemporânea de Serralves, Porto ; Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2013 – 2014

→Mira Schendel, Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume, Paris, 9 October – 18 November 2001

Brazilian painter and sculptor.

The daughter of a German-speaking Czech Jew and a Jewish-Christian Italian mother, Mira Schendel spent her childhood and adolescence in Milan. Between 1941 and 1949 her flight to escape Nazism and her post-war “displaced person” passport forced her into an itinerant exile in Europe that prevented her from pursuing her studies. Her awareness of having no particular attachment to either a country or a discipline, plus the double nature of her upbringing – Czech Judaism and Italian Catholicism – undoubtedly influenced her as a self-taught artist. From the time of her arrival in Brazil in 1949, Mira (she had simplified her first name) drew and sculpted but mostly devoted her efforts to painting. Her approach, which focused much more on subject (whether scientific or religious) than on form, brought her close to a group of intellectuals starting in 1955, particularly the physicist and art critic Mário Schenberg.

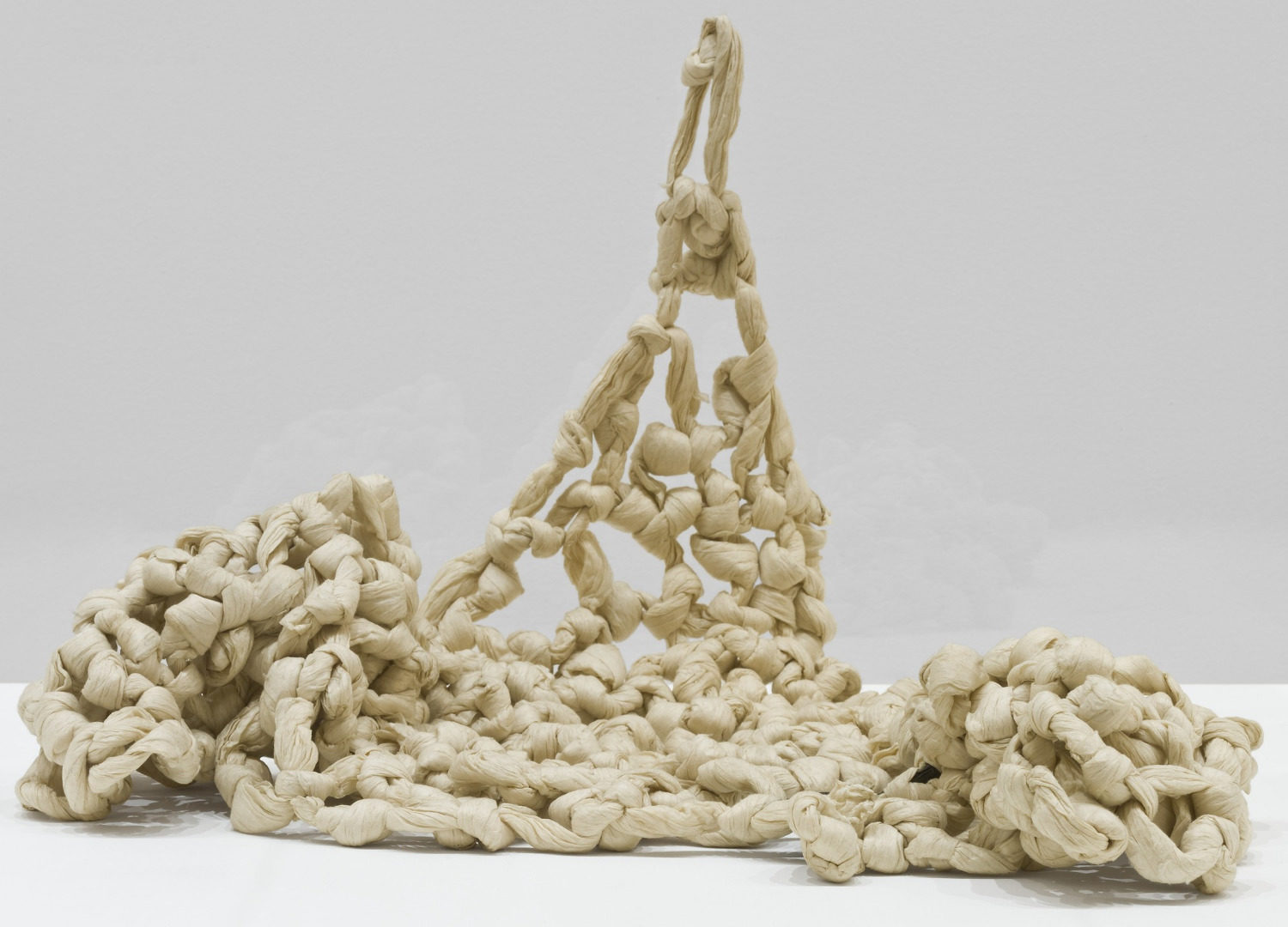

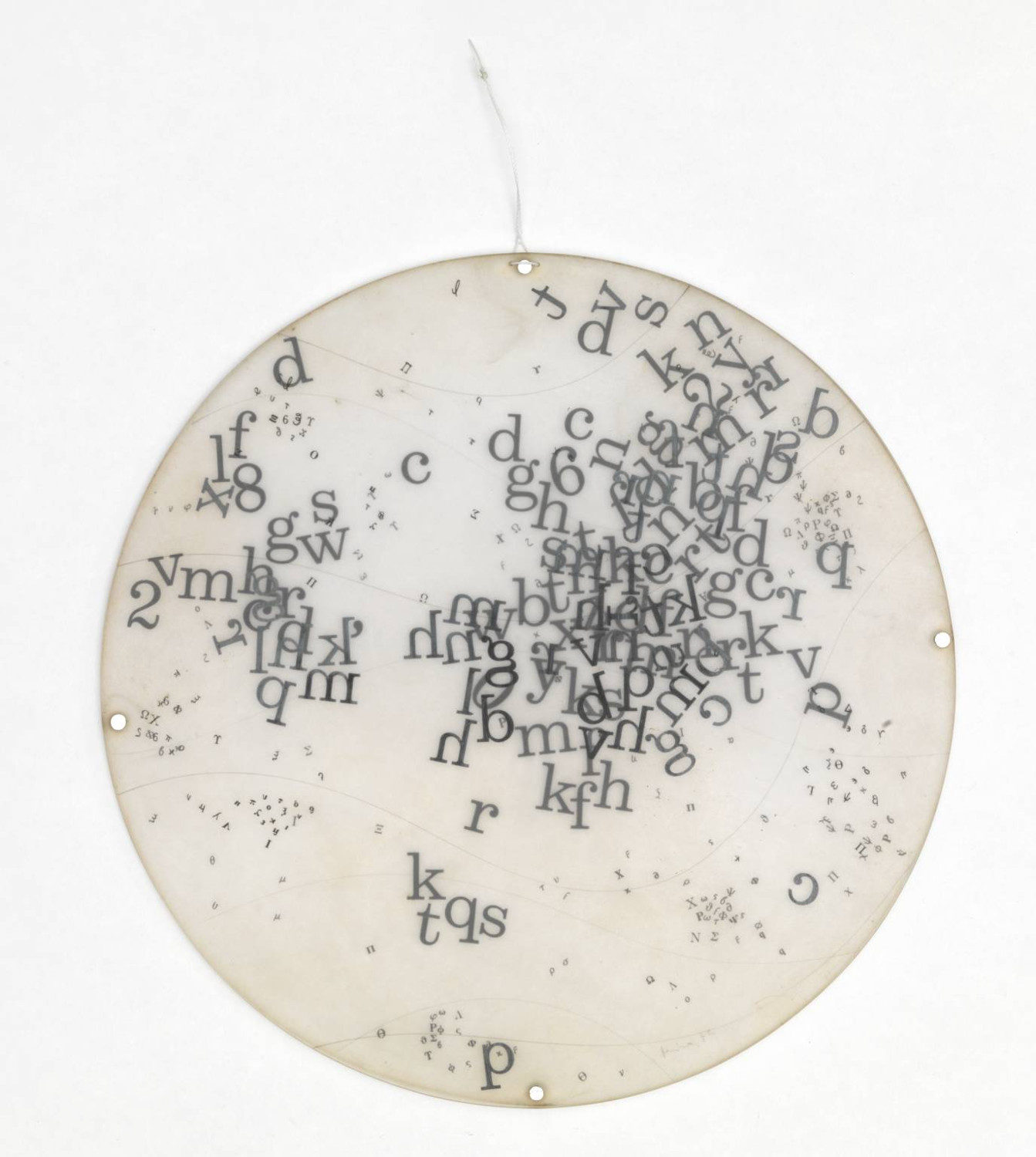

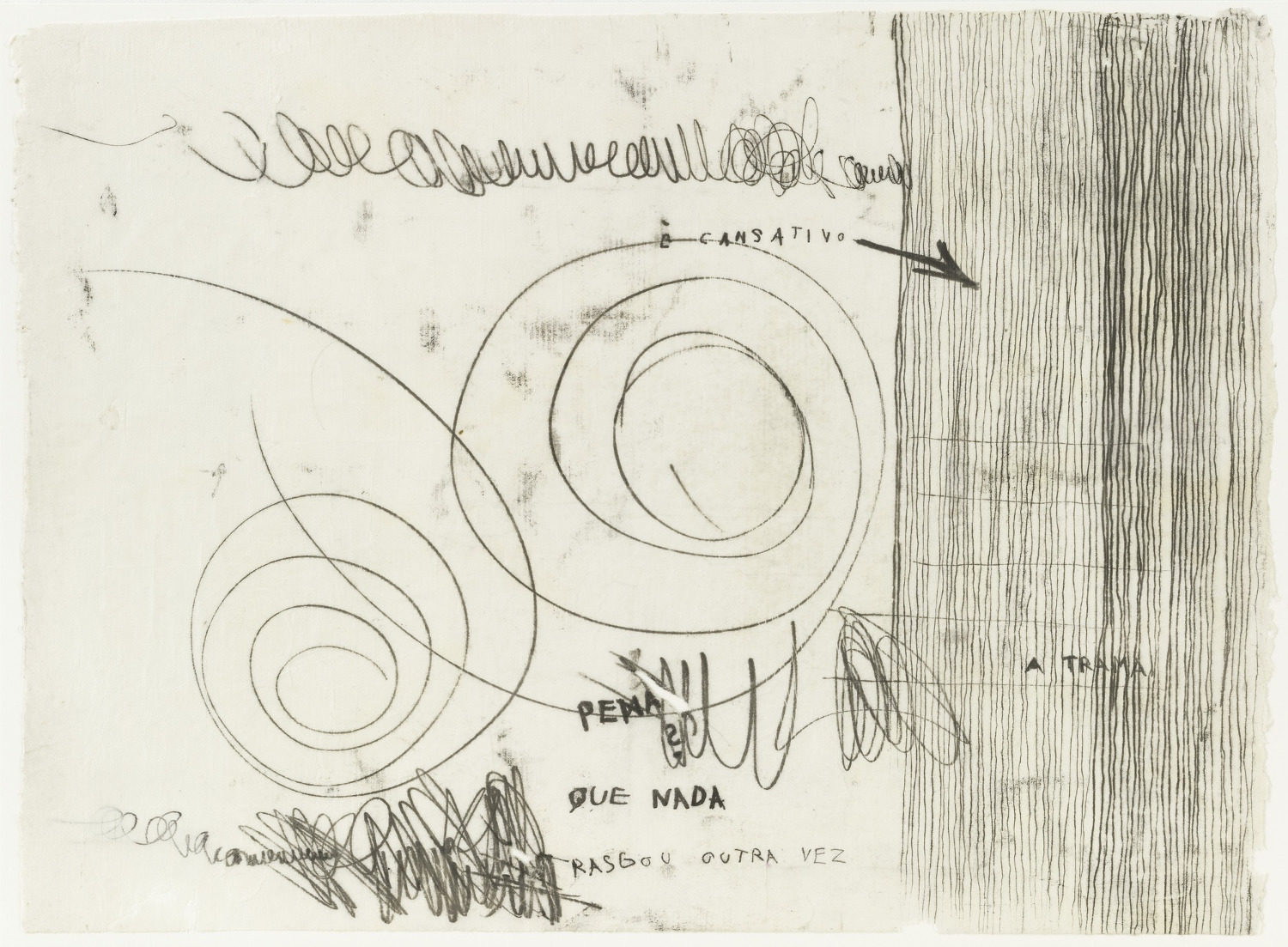

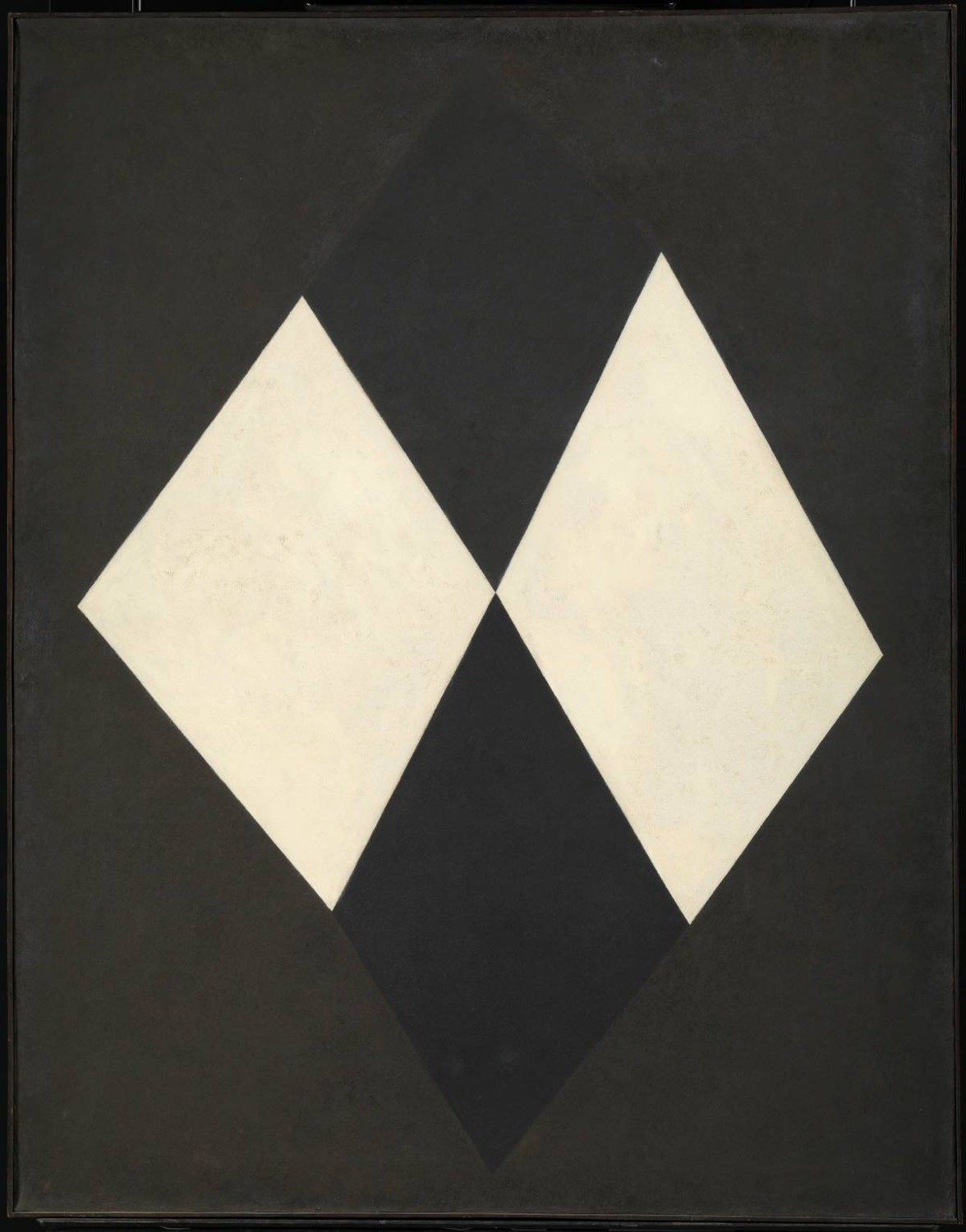

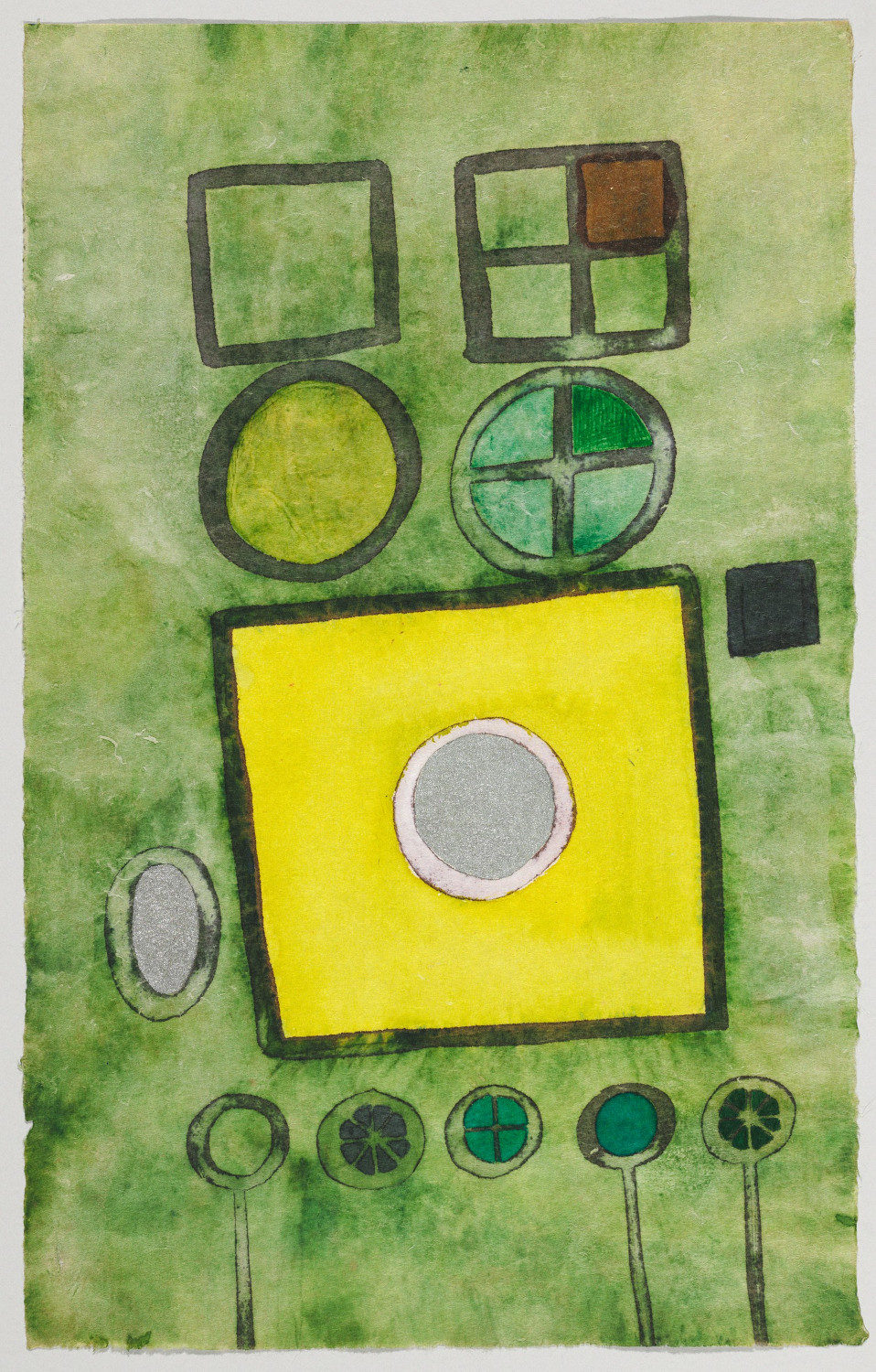

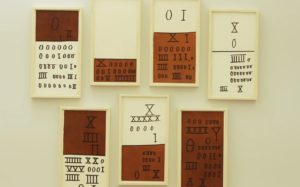

In 1951 her work was included in the São Paulo Biennale. Her concern for the corporal dimension of painting, which was already apparent in her early figurative works inspired by the art of Giorgio Morandi, took on a more radical form at the start of the 1960s with the series Pinturas matéricas, in which she saturated the painted surface with marks made with disruptive strokes. One direction of her artistic research employed light sheets of rice-paper on which she hardly intervened at all: this was the series of Monotypias (which represented two-thirds of her entire output between 1964 and 1967), in which she soaked the paper with ink applied on planks of wood. Composed initially of minimal lines, these works subsequently featured calligraphic and then typographic characters. This method allowed her to embrace in her work the dualism that obsessed her (her Jewish-Latin heritage), and permitted a reading both from left to right and right to left. Some of the monotypes suspended between sheets of Plexiglas became Objetos gráficos, which were shown at the 1968 Venice Biennale. From time to time she also practised tempera painting, including her last series, Sarrafos, which remained unfinished at the time of her death. She made sculptures – also of paper – that she called droguinhas [“little things”, 1966].

In the early 1970s the series Cadernos [“notebooks”] and Datiloscritos [“ink on paper”] took her explorations involving writing a step further, which, despite the return to her first figurative motifs in the years leading up to her death, was the most important contribution made by this solitary, intellectual and mystical artist. She had many exhibitions, amongst them the retrospective Tangled Alphabets, in which her work was presented in 2009 with that of the Argentine artist León Ferrari at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

© Éditions des femmes – Antoinette Fouque, 2013

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2019

Mira Schendel: Stimulating Space

Mira Schendel: Stimulating Space  Sinais / Signals Mira Schendel

Sinais / Signals Mira Schendel  Mira Schendel. Sarrafos and Black and White Works

Mira Schendel. Sarrafos and Black and White Works