Prix AWARE

© Christopher Adams

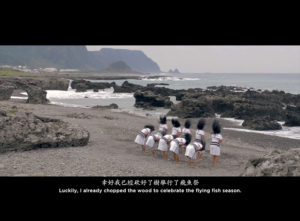

Green Island Human Rights Art Festival, 2020

If on the margin, draw a coordinate

Curated by Sandy Hsiu-Chih LO

Green Island White Terror Memorial Park, Taiwan

Exhibited works: Numbers, 2020, and Songs We Carry, 2017~2018

Lanyu – Three Stories, 2021, 3 HD Videos with sound, 4 min each

In collaboration with Tsering Tashi Gyalthang

An Aspiration, 2020, various objects including shells, bones, and stones hand-inscribed with prayers, dimensions variables

The word flow comes from the Latin fluere. It signifies a perpetual change in nature, a “fluxion” like entropy, the degradation of energy, the permutation of order, a universal moment present in “everything”, like the flux of music, impossible to segment moment by moment. For JJJJJerome Ellis, poet, musician, and stutterer, the two words fluent and dysfluent come from the word fluere, and link dysfluency, Blackness, queer, and music, an intersection of causes, of “handicaps”, and of art, as the essence of a non-normative existence, an eradication of the binary. Ellis quotes Toni Morrison on water and remembering: “All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was.”1 The constant return to the source, circular in its repetition, like the flow of water, these fluere thoughts which persist in the work of Charwei Tsai reveal a perception of cosmic time, the planetary deep time which transcends us geologically and spiritually. Expressed in the form of a circle, a fluid and calligraphic gesture, it is the artist’s signature, a magic spell that runs through a series of visual works (video, textile, organic objects), of performances of collective choirs (Songs We Carry, 2017-2018), shamanic dances (Lanyu – Three Stories, 2012), and published works forming an imaginary circle of artists, thinkers, and activists in the magazine Lovely Daze.

A Temple, A Shrine, A Mosque, A Church, installation of hand-woven mats by craftswomen from AI Ghadeer, Abu Dhabi, UAE

View from “Coming Together” (solo exhibition), TKG+, Taipei, Taiwan

Born in 1980 in Taipei, Charwei Tsai was raised in a traditional family, where the importance of women was not fully acknowledged. She quickly distanced herself from this and went to study art history, design, and architecture in the USA. Paradoxically, this is where she found the source for her spiritual work; in the accounts of the immigration of the Tibetan community in New York in the 1960s – a consequence of the ban on spirituality during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) – as well as in the Fluxus movement, which, by its intuitive and process-driven approach to art performed in daily life, brought together exiled artists, largely displaced by the Second World War.

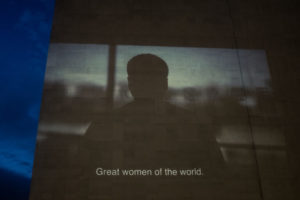

Performance of Circle, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France, 2022

Sound for Circle by Davaajargal Tsaschikher

Curated by Simona Dvorák and Linus Gratte

Photo Courtesy of Centre Pompidou & the artist.

From a Dust Particle to the Universe, 2021, Durational performance and installation with natural cinnabar pigment & ink

Live Forever Foundation National Taichung Theatre (Opera House) Taichung, Taiwan, 2021

Photo by Anpis Wang, Courtesy of Live Forever Foundation

The Womb & The Diamond, 2021, installation of mirror, hand-blown glass, and a diamond

Live Forever Foundation, Taichung, Taiwan, 2021

Photo by Anpis Wang, Courtesy of Live Forever Foundation

C. Tsai immersed herself into a study of Buddhism, Zen and Tantra, which she developed through multiple trips to Asia, dialoguing with monks, in order to deepen her artistic work and her relationship with the public. Fascinated by mystic and shamanic rituals, she finds them to be the pinnacle of artistic performance: in the simplicity of the gestures, the intention is often linked to some form of healing and to the essence of the superconscious. Recently, she embodied this concept in her performance Cercle (2022), in which she drew a calligraphic circle on a block of ice in the grand theatre of the Centre Pompidou; the paint dispersed, the cercle stretched, withered, and disappeared. The sounds that the block made were captured and amplified, drawing our attention to the presence of invisible mechanisms, the natural response to heat. Accompanied by the musical score by the Mongol sound artist Davaajargal Tsaschikher, Cercle invites us to contemplate the elements.

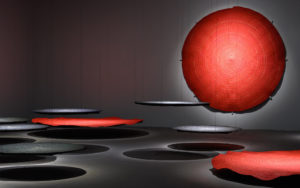

Hear Her Singing, 2017, installation view, Southbank Centre, London.

Photo: Amas Amat Amo.

Lullaby for Mother Nature, 2020, performance by Mongolian artists Ganzug Sedbazar & Davaajargal Tsaschikher

Produced by Charwei Tsai

For the occasion of Lovely Daze Issue 11 book launch

TKG+, Taipei, Taiwan

Photo by Anpis Wang, Courtesy of TKG+

This cosmopolitan and rootless artist has continued to explore her spirituality through many years and many journeys in the indigenous mountain regions of Taiwan, villages in Abu Dhabi, the Gobi Desert in Mongolia, in Java, in Indonesia, and in Japan. Though her work highlights social injustices, inequalities, forced migration (Songs of Chuchepati Camp, Nepal, 2017; Songs of Migrant Workers of Kaohsiung Harbor, 2018), incarceration in camps (Hear Her Singing, 2017) and prisons (Numbers, 2020, at the Green Island Human Rights Art Festival in Taiwan), Charwei Tsai does not consider herself to be an activist, but rather an intermediary between art and the world.

Earth Mantra, 2009, photograph

Sea Mantra, 2009, photograph, 89×127 and 127x81cm

Photographed in Sydney, Australia

Commissioned by Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation, Sydney, Australia

Amongst other things, the fact that she wrote the Heart Sutra, a spiritual text on the Buddhist concept of impermanence, with vegetal and mineral pigments on ephemeral objects (Tofu Mantra, 2005; Mushroom Mantra, 2005; Lotus Mantra, 2006; Olive Tree Mantra, 2006…), then let it be transformed through physical decomposition, constitutes an essential announcement of interdependence; like an empty form opposite a solid form, it is both an expression of finiteness and infiniteness. In Sky Mantra, Earth Mantra, and Sea Mantra (2009), the Heart Sutra covers a mirror which reflects natural atmospheric differences, recalling the ideas of the artist and philosopher Denise Ferreira da Silva, for whom the “past” and “history” are but a transmutation of and a cosmic interconnection with the present, a concept she terms deep implicancy.2 This phenomenon applies to our era and encompasses “the movement of peoples, the movement of clouds, ideas, the earth, the migration of matter at the quantum level from one state to another”.3

Kalachakra, 2021, In collaboration with Khorolsuren Dagvajantsan & Tsaschikher Tsagaankhuu, a pair of hand-crafted and embroidered felt from Mongolia

Live Forever Foundation, Taichung, Taiwan, 2021, Photo by Anpis Wang, Courtesy of Live Forever Foundation

Balaubulau – A Study, 2018, HD video with sound & colorm 12’38’’

Sponsored by Live Forever Art Foundation, Taichung, Taiwan

Ancient Desires, 2023, ceramic offering vessels on exhibit at Making New Worlds: Li Yuan Chia & Friends

Co-curated by Hammad Nasar, Sarah Victoria Turner, and Amy Tobin

At Kettle’s Yard & Jesus College, University of Cambridge, UK, until 18 February 2024.

Photo by Jo Underhill

Coming Together, 2022, textile made in collaboration with Bulaubulau Aboriginal Village, Yilan, Taiwan

View from “Coming Together” (solo exhibition), TKG+, Taipei, Taiwan, 2022, Photo by Anpis Wang, Courtesy of TKG+

Charwei Tsai incorporates the idea of interdependence in every aspect of her work; she thinks about the way funds are used in a circular economy by sharing them with the craftswomen and communities with whom she works closely (Ndewa & Hamanangu Series, 2021; Kalachakra, 2021…) and by trying to preserve memory and oral crafts which are disappearing due to globalisation and industrialisation. Her practice is also critical of the neoliberal structures of contemporary art and of modern society which dominate the economy and totally deplete natural resources as well as the human spirit. The artist calls for durability and the sharing of resources (Bulaubulau – A Study, 2018), replacing the ravages of dissatisfaction with a daily practice of offerings and of solidarity (Ancient Desires, 2023). Finally, her work could be described as profoundly humanist, in a constant quest of healing and of relational attention, denouncing colonial, racial, and hetero-patriarchal structures which have been inherent since the Enlightenment. Hers is a “poethic” oeuvre, of the elementary avant-garde, which mingles cosmic narratives and atomic movements, like a silent and quantum musical score of ancestral desires.

Simona Dvorák

Charwei Tsai was born in 1980 in Taipei, Taiwan. She currently lives in Paris. Oscillating between the personal and the universal, her work raises questions about the relationship between man and nature. She draws on geographical and social sources through the involvement of spiritual and ancestral knowledge, as well as science, to elucidate a union between species, spirits and the environment. This union is often manifested through documentary and contemplative videos or the calligraphic writing of mantras on diverse and often living supports: trees, tofu, mushrooms, lotus leaves, etc.

Charwei Tsai’s work has been exhibited at the Gwangju Biennale (2023); In the Present Moment at the Banff Art Centre, Canada (2023); World Classroom at the Mori Art Museum, Tokyo (2023); Forum Climat at the Centre Pompidou, Paris (2022); and Tate Modern, London (2022), among others. She is a member of the Initiative for Practices and Visions of Radical Care and contributed to the radio project On Care and Resilience at documenta fifteen in Kassel (2022). Tsai’s work can be found in public and private collections, including the Tate Modern in London, the Queensland Art Gallery in Brisbane, the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo, the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, the M+ Collection in Hong Kong, the Faurschou Foundation in Copenhagen, the Kadist Foundation in San Francisco, the Institut d’art contemporain in Villeurbanne (Rhône-Alpes) and the FRAC in France. Since 2005 Tsai has published a bi-annual journal entitled Lovely Daze.

Toni Morrison, « The site of memory », in William Zinsser (ed.), Inventing the Truth. The Art and Craft of Memoir, New York, Houghton-Mifflin, 1995, p. 99.

2

Waters : Deep Implicancy (2018), 31 minutes, directed by Arjuna Neuman and Denise Ferreira da Silva.

3

Ibid.

Tous droits réservés dans tous pays/All rights reserved for all countries.