Interviews

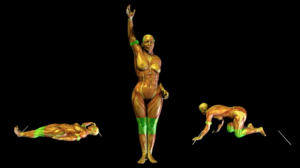

Orlan, Peking Opera Facial Designs No. 10, 2014, colour photograph, 120 x 120 cm, 47 x 47 in., © ADGAP, Paris

Nathalie Ernoult: You say that your body has become a site of public debate. By making your body the raw material of your work, you could have slid into a narcissistic approach.

How did you manage to avoid that?

ORLAN: The idea is to oscillate between object and subject.

Narcissism is absolutely useful and vital for survival. But of course we must not get lost in our own reflection. All of my artworks can be considered self-portraits, although I feel as though I am unrepresentable and unfigurable. Any image of myself can be considered a pseudonym, whether it is a carnal presence, or verbal, or medical … Any representation is insufficient, but not producing any would be worse. That would amount to being faceless, imageless, without representation.

NE: Identity is a major theme of your work. What relationships are there between a human being and their body? To what extent is it possible to modify one’s physical appearance without the perception of one’s own identity being modified?

O: I love mutant, multiple, shifting, and nomadic identities. Our identity evolves endlessly, depending on what happens to us and on our environment. Nature shows us the way of transformation and physical change, from the appearance of a baby to that of the same being who becomes a teenager, then an adult, then an old man or woman, then a very old man or woman. Our physical appearance is completely modified, although we remain the same person. I think that old ideas haunt us and make us believe that we cannot attack the body. However, patellae, or hips, teeth, or even hearts can be replaced, and, recently, facial grafts have been performed.

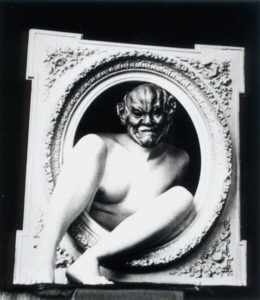

Orlan, Kiss of the Artist, 1977, black and white photographs, wooden plinth, flowers, plastic lettering, chair, soundtrack, 225.5 x 170 x 70 cm, 88.5 x 67 x 27 in., © ADGAP, Paris

NE: You have written a manifesto on carnal art, distinguishing it from body art, notably in terms of the question of pain… How does “carnal art”, as you have called it and worked on it, differ from “body art”?

O: Carnal art is self-portraiture in the traditional sense, but with the technological means that are those of its era. It oscillates between disfiguration and refiguration. It is inscribed within the flesh because our era is starting to make this possible. The body becomes a modified ready-made since it is no longer the ideal ready-made that just requires the artist’s signature.

Unlike body art, from which it differs, carnal art does not desire pain, does not seek it out as a source of purification, and does not consider redemptive. Carnal art is not interested in the final plastic result, but in the surgical-performance operation and in the modified body that becomes a forum for public debate.

NE: In 1977, at the FIAC, you created a plastic work that featured in the FRAC collection of the Pays de la Loire, based on which you gave a performance: Baiser de l’artiste.

O: The sculpture comprised a large base (225.5 ´ 170 ´ 70 cm), a life-sized photo in which I was disguised as a Madonna, Saint ORLAN, whom it was possible to worship by buying a candle for 5 Francs. On the other side of the base, there was my bust, cut out and pasted onto wood, which was a kind of kiss dispenser, behind which I could sit and give a real kiss – a French kiss – for 5 Francs. This performance, which denounced the stereotypes of mother and prostitute, took place in the temple of the art market.

NE: What is your relationship to this market today?

O: I created this performance based on a text, “Confronting a society of mothers and dealers”, which started with “At the foot of the cross, Mary and Mary Magdalene”, two stereotypes from which it is difficult to escape as a woman. So, from 1977, I started to denounce the art market. Throughout my work, throughout my life, I have never compromised in order to sell. It is only over the last twenty or so years that some series of my work have been selling well.

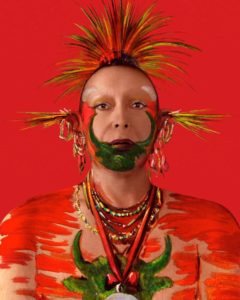

Orlan, Documentary Study : Le Drapé – Le Baroque, Single Brest, Phallic Monstrance, 1983, black and white photography, 100 x 100 cm, 39 x 39 in., © ADGAP, Pari

NE: With your Saint ORLAN character, you rework Judeo-Christian iconography in order to more effectively denounce the diktats of Christian religion that weigh on women’s bodies. What are your connections with religion?

O: To me, God is not a hypothesis of life or work.

I have never had religious teachings; I work on social, political, cultural, and religious pressures that are engraved within female bodies, and within flesh in particular. These days, censorship is returning because religions are turning up the heat. Religions have always been discriminatory and insulting for women since they were made by men and for men. Politicians use them to constrain and manipulate bodies and minds and to impose their power. La Manif pour tous (LMPT) tries to govern and prohibit our freedom. For artists working with their bodies, if there is no freedom anymore, expression is no longer possible.

Everyone has a body; everyone knows what it’s like to have a body. When you’re a believer, it is said that humans are made in the image of God, so it seems absurd not to show bodies, nudity, genitals, or sexuality.

We are currently experiencing an incredibly ludicrous degree of censorship with Joep Van Lieshout’s work Domestikator (2015), which was banned from the Tuileries Garden even though it was part of the FIAC outdoor works programme, or with Paul McCarthy’s Tree (2014), which was vandalised three years earlier.

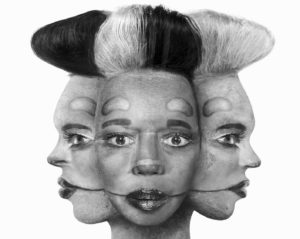

Orlan, African Self-Hybridization, Three-Headed Ogoni Mask, Nigeria, with Mutant Face of Franco-European Woman, 2002, color photograph, 125 x 156 cm, 49 x 61 in., © ADGAP

Orlan, Tentative de sortir du cadre avec masque, 1965, black and white vintage photograph, unique print, 6.5 x 10.5 cm, © ADGAP, Paris

NE: Do you think that the Christian religion is still able to impose its diktats? Do you intend to work on the body of Muslim or Jewish women?

O: No. It’s really up to them to do that, but if they need some help with it, obviously I’d be there for them.

NE: Very early on, in your performances, you used your body as a material in order to denounce the stereotypes attached to female beauty. Feminists in the 1970s affirmed that the body was political. Was Self-Hybridations (2007), a series in which you combined various standards of beauty, an illustration of that slogan?

O: Clearly, the body is political, the personal is political, whether we like it or not. The art and artists that interest me are the ones who don’t navel-gaze but who provide a perspective of our society, of the social phenomena of the time, and of the world. To me, artists must have a responsible and well-defined attitude. As a woman artist, I have questioned myself and given my point of view on the stereotypes of female beauty, as with the works that I made based on Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (circa 1484-1485), but also on other social phenomena, such as the art market, with Baiser de l’artiste or Se vendre sur les marchés par petits morceaux (1976-1977).

I have also created artworks against the harassment created through football, which has become a kind of new religion, and lately I’ve created video games in the form of interactive installations that can be played by applying one’s whole body to them. Thus, these are games in which killing is not a game. The Self-Hybridations are post-operational works, made with my face transformed by the technology of surgery that suggests providing hospitality and the culture of otherness by mixing and hybridising beauty standards, or even by using my face, as I attempt to move away from beauty standards.

NE: By using your own body as a unit of measurement of various public spaces, you have applied Protagoras’s expression to the letter: “Man is the measure of all things.” In so doing, you have confronted your own reality, that of your body, with that of an established convention – the standard metre or yardstick. What are you seeking to demonstrate? Can humanity exist without conventions?

O: I took Protagoras’s expression to the letter. Humanity is the full measure of all things, but humanity, and in my case womanhood, since it was a question here of using my own body as a unit of measurement,1 to measure museums and/or streets bearing the names of the consecrated stars of art history. However, at the same time, I questioned this consecration made by men and for them. Few streets bear a woman’s name. I registered an “ORLAN-body”, an instrument with which people can choose to measure the world. Incidentally, Jan Fabre used it for a performance, in order to measure his new theatre in Antwerp, called Troubleyn. I am very keen to confront the standard metre by measuring the meridian line that runs through the Monnaie de Paris, while a custodian of the standard measure measures that same distance.

Orlan, American Indian Self-Hybridization #11: Painting Portrait of La-doo-ke-an, Buffalo Bull, a Great Pawnee Warrior, with ORLAN’s Photographic Portrait, 2006, digital photography, 152.5 x 124.5 cm, 60 x 49 in., © ADGAP, Paris

NE: Your whole body of work favours difference over similitude, plurality over singularity, multiplicity over unity, diversity over uniformity, heterogeneity over homogeneity. How do you explain this desire to cause the uniqueness of your body to disappear while integrating it into that of others or by integrating that of others into yours?

O: The devil says “I am multiple”, but it is not a question of causing the unity of my body to disappear, since it is not about my body, but its representation and the desire to create an artwork symbolising hospitality, giving other cultures and their representations a place inside me, mixing and hybridizing two works of art from different cultures.

In my work, I always use the lesson of the baroque period that shows us both good and evil at the same time: it represents Saint Theresa, who enjoyed the angel’s arrow in an ecstatic “and” erotic state (Lacan had a lot to say about this), whereas Christian culture asks us to choose either good “or” evil. Photography becomes an extension of this idea, since it has only relatively recently been considered an art, along with new technologies, such as augmented reality, which are having trouble acquiring the same status. It is one of the lessons of the baroque period that I have the most worked with. Many of my works were based on this “and”.

NE: You have always known how to evolve your artistic practice according to new technologies. With the digital era, your body has become virtual and stripped of its skin, as in La Liberté en écorchée (2013). With augmented reality, your 3D avatar juggles with the masks of Peking Opera. We have thus gone from a performance with a carnal body, which measures or produces secretions, to a performance in which the body – your body – is dematerialised. Will your research continue in this vein?

O: As I was saying earlier, what is important is the “and”; I am against neither the virtual nor the real.

The baroque “and” is still with me, since the post-operational works were created thanks to the physical operation and they can be shown by way of a technological intervention. Materiality or immateriality doesn’t interest me in and of itself, since it depends on what I want to say, on the framework. Passing from one to the other is absolutely not a problem for me if it serves my message.

For instance, the Masques, Pékin Opéra Facing Designs et réalité augmentée (2014) were not just created because I’m fascinated by technologies and augmented reality, but because, thanks to them, I’m able to say two important things about the Peking opera. The first is a feminist position since, traditionally, women could not play their own roles, which were instead performed by men. This enabled me to extricate myself from the work by disrupting the rules of Peking opera: by appearing as a woman artist reinventing the acrobatics of the Peking opera. I used new technologies to change mindsets, since we are all immersed in these technologies and yet, as the collectors come to a gallery, they come in their cars, which will soon be autonomous driverless cars, they all have a smartphone in their pocket and take images of their families and friends. They have all the gadgets you can imagine in their homes, they are saturated by new technologies and, yet, when they arrive at a gallery space, they consider that anything that is technological is not art – they want to see and buy drawings and paintings.

So I wanted to make an artwork that looks traditional but, if you download the free application Augment, you can scan the work and bring me out of the work in 3D made from the scan of my animated body, and you can see me do Peking opera acrobatics via my avatar; you can also take a photo with your friends and send the image all over the world, which creates connections and participation.

I’m currently working on my microbiota and above all, for the Grand Palais, on a humanoid that talks and uses my expressions. The Orlanoïde is an evolutive artwork that is based, among other things, on the deep learning system, a technique of automatic learning activated by digital neural networks. Specially devised for the Artistes & robots exhibition, the work takes the form of a hybrid body – both electronic and verbal – that resembles the artist, whose heart is rendered visible through transparency. The whole ensemble is infinitely reflected in mirrors that thus create multiple images of the Orlanoïde. This central robot dialogues with its clone in the form of another head placed on a mechanical arm and a pedestal. From the other side, a big LED screen broadcasts a pre-recorded video showing two other faces of ORLAN, who directly question the robot, using collective intelligence. Thanks to this dialogue and to the transparency of this robotic body, the work has the appearance of an electronic and verbal strip-tease. It falls within an artistic approach that consists of questioning the status of the body in society, by highlighting the cultural, traditional, political, and religious pressures that are engraved within bodies. With Orlanoïde, the artist once again questions this status, this time, in relation to the new technologies that seek to reconstruct and reinvent bodies.

ORLAN is presenting her work as part of the Artistes & robots exhibition at the Grand Palais, in Paris, from 5 April to 9 July 2018.

ORLAN, MesurAGEs, since the 1970s.

Nathalie Ernoult et ORLAN, "ORLAN, between artist and robot." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/orlan-entre-artiste-robot/. Accessed 15 July 2025