Research

On a black background, white text frames an image of a couple embracing: she leans in and grips his hair, he holds her waist but keeps her at a distance. The text reads “What does possession mean to you? 7% of our population owns 84% of our wealth”. The power relation of the pose is ambiguous and only tangentially related to the quantitative statistics of the accompanying slogan. Possession (1976), by Victor Burgin, was printed on the back of issue three of the British photography magazine Camerawork. With offices located at 121 Roman Road in East London,1 the magazine (1976–1985), founded by a collective of London-based photographers, advanced the notion of photography as a tool of representation with a left-wing political efficacy. In his editorial, Burgin writes that Camerawork “…has raised the issue of photography as an instrument of ideology”2. Today, leaving no. 121 and looking east, you are met with a view of Canary Wharf, glinting like a sundial3 from the London Docklands financial district. The Docklands no longer receive cargo by water, but is an effective “free enterprise zone” for trading, which since 1988 has transformed the economic and physical landscape of East London. Today in the UK, fifty families hold more than half the country’s wealth. What does possession mean to you?

Victor Burgin, Possession, 1976, duotone lithograph, 118.9 × 84.1 cm. © Arts Council Collection / Bridgeman Images.

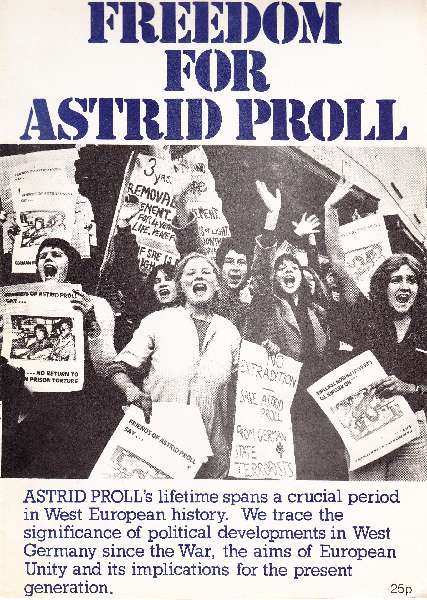

In 1974 a young woman travelled to London from the Federal Republic of Germany, using false documents to cross the pre-Schengen Agreement borders of Europe with relative ease. In Germany during three years of imprisonment, she had experienced solitary confinement, for her early involvement in the group that would become the Red Army Faction (RAF) and the freeing of the left-wing radical agitator Andreas Baader.4 Astrid Proll had not visited the UK prior to her escape and had few contacts, but via individuals sympathetic to the cause, she found her way to a group of squatters and feminists associated with Left Libertarianism and the revolutionary socialist group Big Flame. She lived in London under the assumed identity of Anna Puttick for three years before being re-arrested and eventually extradited back to Germany. For some of that time, she shared a squat in Bow, an area of East London close to Bethnal Green where Camerawork was based, and just north of Canary Wharf.

Before her involvement with the RAF, Proll had been a photography student, and later in life she became a picture editor for magazines and newspapers. Decades after her stint in London, she co-curated an exhibition and published a book titled Goodbye to London: Radical Art and Politics in the 70s (2010). This project combined the work of a diverse group of producers, including essays by witnesses to the time such as Jon Savage, and artist pages by the queer filmmaker Derek Jarman and the feminist photographer and co-founder of Camerawork magazine Jo Spence, alongside documentary photographs of squats. In her introduction, Proll writes: “The squats were the material basis and precondition for the emergence of political activism, art, and alternative life. These houses, removed from the circulation of capitalist valorization, were open spaces for experimentation of all kinds towards a life lived without economic constraints”.5 The heterogeneity of Proll and her colleagues’ selection of work was critiqued by some reviewers,6 but it is precisely a lack of uniform belonging, collectivity formed through association and not through shared characteristics or identity, that Proll describes in her celebration of the squatting movement. One could frame it as a negative identity category, formed by the universal need for housing, freed from market discipline.

Proll’s description of her time in London is laced with romance. Out of prison, embraced by the Women’s Movement, Proll eventually found a place for joy. In an interview with Ian Sinclair, Proll is quoted as saying: “In England people use words like ‘pleasure.’ ‘This gives me pleasure.’ I used to shout and say ‘What are you talking about? Pleasure? What is that?’”7 Yet her experience was contradictory, enriched by communal life and through manual and political activity,8 it was also conditioned by an ambient fear of identification and re-arrest. Photography and cameras were a particular concern. Proll’s initial arrest in Germany in 1971 had come after a policeman had recognised her from the passport photo used in police communiqués.

In her text for Goodbye to London, Proll recounts the publication of Hitler’s Children: The Story of the Baader-Meinhof Terrorist Gang (1977), a critical and sensationalist account of the RAF by Jillian Becker which included a portrait of Proll. Worried the mass popularity of the book would lead to her being uncovered, a group of her friends searched local bookstores and stole the book or tore her image from it; redacting her face from the criminal catalogue in an act that was both petty vandalism and iconoclastic de-documentation. A funny story, but the tearing of the page, Proll’s image pulled from circulation, is both performative and analogous to the purpose and function of documentary. Photography is not one thing, it comprises of the event of the shot, the technology of the camera, the process of printing and fixing, the material the image is distributed through, and the meaning that is made for the image through discourse. In Becker’s book the photo of Proll was of a wanted terrorist-associate, the image reproduced was taken from a forged document Proll had used while on the run, found in a safe house she had fled in a hurry. For her friends the photo was a threat, endangering a woman they knew as a colleague, comrade and companion. Their minor-criminal act, a forced redaction, was an attempt to destabilise the meaning inscribed onto image by Becker. Perhaps it is helpful to invert Burgin’s slogan and ask: What does dispossession mean to you?

In his 1986 essay The Body and the Archive, photographer and theorist Allan Sekula described how the triangulation of photography, property and the police forms and contains the photographic subject. He traces a history of police surveillance alongside the development of photographic portraiture as a cultural form. The essay proposes a double bind of the honorific and repressive nature of photography. The subject is pictured because of their value. That value can be sentimental, or it can be political. They can have high social worth or be sought by the carceral state. A passport photo, for example, allows freedom of movement but also acts as a marker of state and extraterritorial surveillance. Sekula’s explicitly Foucauldian theory of photographic representation and power attaches photography to the collaborative institutions of the modern nation-state, organised for the protection of bourgeois values – namely private property.

However, it is not just that photography can be made to work in the service of property and property relations, but that the subject of the photograph becomes divisible by these hierarchies of value. Sekula uses the example of policeman and photographer Alphonse Bertillon, whose Synoptic Table of Physiognomic Traits (1909) presents segmented photographs of facial features in a grid-like structure, printed for use in detective work to aid identification of criminals and criminal types. Of course there is no such thing as a specifically criminal ear, eye or nose, but following Sekula we can understand bertillonage as the introduction of economic equivalence between form, meaning and value, to the human body, via photography and its claims for indexicality. The potential to reconfigure a whole human into an assemblage of characteristics that can be isolated from each other was revolutionary and has organised the relationship of the citizen to the capitalist state in ways still unfurling. Today, we are familiar with how surveillance technology uses our image for convenience and security, be it a workplace ID card or IOS face recognition, to discipline and control. We all occupy a state of pre-criminality in which we are both the potential perpetrator and potential victim. The split between Proll’s identity, as a member of a terrorist organisation in Germany, and as the participant in a communitarian political milieu in London, in some ways prefigures this generalised experience and troubles the boundary of innocence and criminality set in place by the iconography of surveillance images.

After Proll’s arrest and eventual deportation, she was released in Germany in 1981 and studied film in Hamburg with Helke Sander.9 Following her studies, Proll worked as a picture editor for the culture and lifestyle magazine Tempo, and in the mid-1990s was able to return to London to work on the picture desk at The Independent newspaper, located in the new Canary Wharf. Her employment was cut short when the editor of the internal Canary Wharf trade paper became aware of her past and ran an exposé, distributing an image of Proll’s face and an account of her activities with the RAF to every desk in the building. Initially supported by her colleagues, her position at the paper was ultimately deemed untenable, primarily due to the proximity of the1996 Provisional IRA bombing of Canary Wharf, which killed two people and injured more than one hundred. By the late 1990s, the violence of the anti-capitalist revolutionaries of the 1970s was long gone. Re-unified Germany was becoming a dominating power in the quickly federalising European Union. The crimes of the RAF were hardly a threat to international finance as administered from Canary Wharf, but Proll’s image served as a reminder of the excesses of violence, not just from her own time but from the then ongoing terrorist activity of the IRA. Framed by outrage, Proll’s face did not communicate her own personal story but stood as a representation of “a terrorist”, and once again, her image provoked rupture and dispossession, this time from her job.

Do any of us really own our own face or name? And if we all exist in a state of privation, how can we describe our experiences outside of the binds and metaphors of property relations? In Chris Petit’s Radio On (1979), the graffiti ‘FREE ASTRID PROLL’ is seen from a car window, painted on the underside of the Westway leading out of London. The graffiti was put there by a friend of Proll’s, who cycled around London protesting her forthcoming deportation. Throughout Radio On, shot by German cinematographer Martin Schafer,10 the car windscreen is presented as a frame which pushes the viewer forward. However, in the Westway sequence, Schafer’s camera attaches itself to the graffiti. Momentarily distracted from the journey, the car drives on, the camera pans from the front windscreen to the passenger window, and the viewer is briefly held back. Unless the viewer is familiar with the significant but under-historicised story of Astrid Proll, the shot registers as distracted interest in an act of vandalism and criminal trespass. An informed viewer will note the inscription, in which Proll is represented not by her face or identity, but through an act. All property is alienable, but action is contingent. If we understand our identities and their representation as process, perhaps dispossession is not a punishment but a means of independence.

In 2003, Four Corners, a film and photo organisation with a history intertwined with that of Camerawork, and sharing personnel and thematic interests, acquired the building at 121 Roman Road. Physical copies of the Camerawork archive are now kept in the building they were produced in.

2

Burgin, Victor, “Art, Common Sense and Photography”, Camerawork Magazine, issue 3, July 1976.

3

See William Raban’s short portrait of Canary Wharf, Sundial (1993) https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-sundial-1993-online.

4

This freeing of Baader marked the formation of the RAF or Baader-Meinhof Gang. Baader was in prison for an arson attack on a department store, an early incident in Baader and his collaborators’ attacks against German industry, commerce and private wealth. Gudrun Ensslin organised an interview between Baader and the sympathetic journalist Ulrike Meinhof to provide a cover for Baader’s escape. Meinhof then joined Baader, Ensslin and the others in their activities.

5

Proll, Astrid Goodbye to London: Radical Art and Politics in the 70s, Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2010, p. 11.

6

Kidner, Dan, “Goodbye to London – Art and Politics of 1970s London”, Lux, March 16, 2011. https://lux.org.uk/goodbye-london-art-politics-1970s-london-lux.

7

Sinclair, Ian, Hackney That Rose Red-Empire: A Confidential Report Penguin Books: London: 2009 p.556.

8

Proll worked at the Lesney toy car factory and took part in the Dagenham factory strikes of 1975.

9

Sander is one of the most important feminist filmmakers to emerge with the New German Cinema of the 1970s and had been in the same year at the DFFB film school as RAF member Holger Meins.

10

Petit came to work with Schafer via Wim Wenders, Schafer was Wender’s assistant cameraman and had recently worked on The American Friend, a neo-noir film that also includes a shot of graffiti, relating to the death of Holger Meins. Released in 1977, the year that RAF members Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin and Jean Carl Raspe died in Stammheim Prison, The American Friend refers to Meins’ earlier death while in state custody in 1974, the year that Proll reached London.

Alexandra Symons-Sutcliffe is an art historian who writes and curates. She is currently a PhD candidate at Birkbeck University, London where she is completing a dissertation on British documentary photography from the 1970s and 1980s. She has organised and contributed to exhibitions and events programmes at organisations including Halle für Kunst Lüneburg (DE), Four Corners (UK), MayDay Rooms (UK), Gallery 44 (CA), Cabinet Magazine (DE), The Kitchen (US) and the Whitney Museum of American Art (US).

Alexandra Symons-Sutcliffe has been researcher-in-residence at the Villa Vassilieff as part of the AWARE residency programme for research on women and non-binary photographers and video artists, which received the support of Neuflize OBC Foundation.

Alexandra Symons Sutcliffe, "Dispossessed: Portraiture and Property in the Case of Astrid Proll." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/depossedee-sur-le-portrait-et-la-propriete-dans-le-cas-astrid-proll/. Accessed 3 March 2026