Research

Video has become the go-to tool for artistic experimentation ever since it placed the processes of capturing and editing electronic images, until then the privilege of mass media outlets, within the reach of many. From the 1970s/1980s onwards, its home-made and portable formats presented an important platform for exploring new thematic fronts, crossing languages and constructing visual narratives. Itself a medium-language, video has also hybridized with other forms of expression, notably performance, and has generated a vast field for installation-based propositions. To many artists, however, it offered, above all, the possibility of transmuting reality into raw material, posing questions and problems based on the record of something experienced. This strain, which orbits, transcends and adds meaning to documentary practice, is associated with much of the production of Brazilian female artists who, from the 1980s onwards, embarked on the adventure of challenging the hegemonic visual discourse and questioning aspects of sociopolitical reality.This opened avenues for constructing memory and counter-memory, allowing a broader range of voices to participate in shaping Brazil’s cultural and historical narrative.

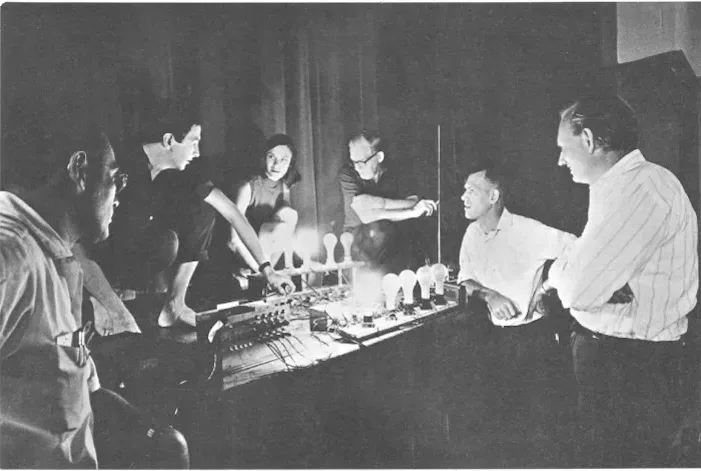

Portrait of Rita Moreira, © Photo: Pedro Napolitano Prata, Courtesy of Videobrasil Historical Archive

Rita Moreira, A dama do Pacaembu, 1980, video, 34 min. 18 sec., Courtesy of Videobrasil Historical Archive

A number of collections and curatorial platforms in Brazil — including independent archives and festivals — allow us to observe the actions of these pioneers and the different forms that the movement they set in motion would take in the following four decades. This is especially true if we consider the essentially political vocation of artistic production in the geopolitical South, a symbolic region that has become central to recent curatorial research. These artists would initially dedicate themselves to confronting the invisibilisation of dissident subjectivities and the social agenda, an ever-pressing issue, but even more so during the long period of the Brazilian dictatorship (1964–1989), which had control of information as one of its pillars. An important early example is Rita Moreira (b. 1944), who has created an exemplary body of work in the search for silenced visions and themes, marked by a feminist perspective. Since her formative years at the New School for Social Research in New York, she has appropriated the standard format of news broadcasting to talk about what it avoided: the politics of appearance, beauty standards, persecution of homosexuals and structural racism. Her pioneering stance laid the groundwork for generations of politically engaged artists, inspiring a legacy of feminist critique within and beyond video art.

With delicate irony, her A Dama do Pacaembu (1981) approaches Brazilian inequality through the discourse of a woman who lives on the streets of the title’s wealthy neighbourhood, and who believes to be a member of the surrounding decadent .nobility”. Moreira has continued her video activism in support of progressive causes and against abuses of power; one of her most recent works, Caminhada Lésbica por Marielle (2018), records a protest by feminist and LGBTQIA+ activists against the assassination of Rio de Janeiro congresswoman Marielle Franco that same year. In a country with growing violence and a record number of feminicides, it was only in 2024 that two police officers were charged with her murder.

Portrait of Lucila Meirelles, © Photo: Pedro Napolitano Prata, Courtesy of Videobrasil Historical Archive

Lucila Meirelles, Crianças autistas, 1989, video, 11 min. Courtesy of Videobrasil Historical Archive

In the 1980s and 1990s Lucila Meirelles (b. 1953) set out on a similar path, with works of a metalinguistic and experimental nature, often guided by the search for points of view away from established parameters of normality. A pioneer of video art in Brazil, alongside such artists as José Roberto Aguilar, she explores this idea in experimental documentaries such as Crianças autistas (1989) and Cego Oliveira no sertão do seu olhar (1998), poetic investigations that delve into the subjectivity behind the psyche and vision of people with disabilities.

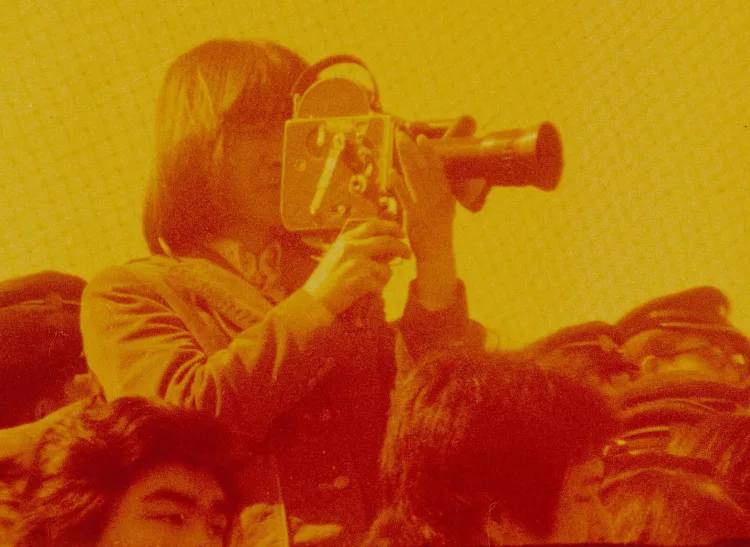

Portrait of Sandra Kogut, © Photo: Videobrasil Historical Archive

Sandra Kogut, Videocabines são caixas pretas, 1990, video, 9 min. 36 sec. Courtesy of Videobrasil Historical Archive

In the 1990s, in an atmosphere of democratic reconstruction and globalisation, Sandra Kogut (b. 1965) emerged with a work focused on the investigation of electronic visual language itself, moving between video installation, video, television and cinema. Her Videocabines (1990) project stands as a significant early example of how digital images began shaping a scenario increasingly marked by exposure and notoriety. In it, the artist sets up video booths in cities around the world and invites anonymous passers-by to record their thoughts. Kogut continued to work extensively, in cinema, and in 2023 she made No céu da pátria nesse instante, a documentary about the elections that interrupted (for now) the rise of the far right in the country and the attacks on the symbolic institutions of Brazilian democracy on 8 January 2023. Her trajectory across multiple platforms reveals how the moving image can continually reinvent itself as a site of civic engagement and public reflection.

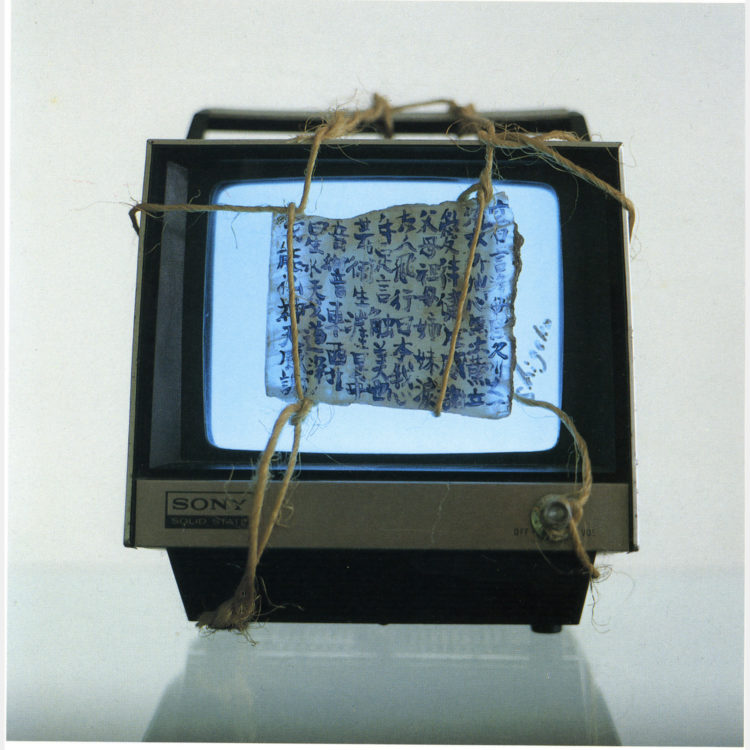

Portrait of Rosângela Rennó, © Photo: Renata D’Almeida, Courtesy of Videobrasil Historical Archive

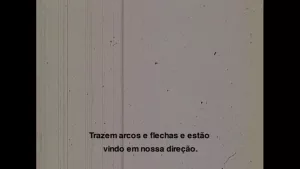

Rosângela Rennó, Vera Cruz, 2000, video, 44 min. Courtesy of Videobrasil Historical Archive

The exponential multiplication of visual narratives made possible by increasingly easier access to digital means of production was echoed, from the 2000s onwards, in works that address the nature of the image, its symbolic value and its process of depersonalization. These questions are explored in depth in the extensive work of Rosângela Rennó (b. 1962). Her photographic series, objects, videos and installations often begin with her appropriating anonymous images, found in antique fairs, family albums, newspapers and archives. In Vera Cruz (2000), the artist reinterprets the letter sent by Pero Vaz de Caminha to the Portuguese king upon the coloniser’s arrival in Brazil. Around the text and the distorted image of a veiled film, the artist constructs an “impossible documentary”, contrasting the flat, nuance-lacking version of the letter that was perpetuated by schoolbooks, to another one, full of sound and image gaps to be filled in by the viewer. Like many of her works, the video attests, in the words of curator Paulo Herkenhoff, to “the dissolution of grand narratives and a unitary perspective of history”,1 pointing to a necessary political education of the gaze in contemporary times. Her manipulation of archives acts as a strategy for both recovery and disruption, re-signifying what official history omits or silences.

Portrait of Rivane Neuenschwander, © Photo: Raul Zito, Couresty of Videobrasil Historical Archive

Rivane Neuenschwander and Cao Guimarães, Word – World, 2001, video, 8 min. Courtesy of Videobrasil Historical Archive

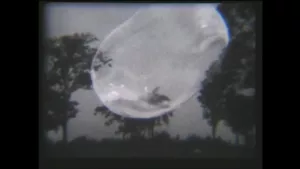

Rivane Neuenschwander and Cao Guimarães, Sopro, 2000, video, 5 nin. 45 sec. Courtesy of Videobrasil Historical Archive

Rivane Neuenschwander (b. 1967), who began working during the same period, uses a myriad of means, resources, processes and connections with various fields of knowledge to address universal issues – fear, history, temporality, political and social interactions, the intercommunicating nature of living systems – in all their complexity. Sprawling across drawing, painting, tapestry, object, installation and collective propositions, her initial production includes a series of video poems created in partnership with the artist Cao Guimarães2, such as Sopro (2000) in which a soap bubble floats about to burst, and Word – World (2001), an unlikely confrontation between ants and the written word. These pieces create delicate and precise images in their ephemerality and incommunicability, exemplifying, according to the artist, the seminal use of video – often showcased in regional and international exhibitions – by a generation formed by cinema, to “exercise philosophical thought”. Over the last years, Neuenschwander has led the performative activism project Reviravolta de Gaia, in which participants dressed as mammals, insects, fish, plants and other entities from nature and take part in large political demonstrations to denounce and combat legal restrictions on the demarcation of Indigenous lands, guaranteed by the Brazilian Constitution of 1988.

Portrait of Cinthia Marcelle, © Photo: Pedro Napolitano Prata, Courtesy of Videobrasil Historical Archive

The idea of carefully orchestrated interventions and actions, capable of generating synthetic images to address major topics, acquires particular potency in the work of Cinthia Marcelle (b. 1974). Her artistic operations, which involve performance, video, action, photography, sculpture and installation and are markedly non-verbal, question social structures, behavioural patterns and power relations. In the words of curator Jochen Volz, they profess “a thought transformed into experiment; an experiment that ultimately translates into image the clear position that art is only about the act of questioning things”.2 In Marcelle’s trilogy of video performances composed by Cruzada (2010), Fonte (2007) and Volver (2009), a fire truck, a backhoe and a heterogeneous group of musicians evolve in apparently random movements over the red earth of Minas Gerais, the artist’s home state, whose environmental and economic fate is tied to the iron ore extraction industry. Through these orchestrated gestures, she questions systems of visibility and the aesthetics of power, challenging the viewer’s role as passive observer.

Portrait of Virginia de Medeiros, © Photo: Renata D’Almeida, Courtesy of Videobrasil Historical Archive

Virginia de Medeiros, Cais do Corpo, 2015, video, 7 min. 2 sec. Courtesy of Videobrasil Historical Archive

Virginia de Medeiros, Sergio e Simone, 2010, video, 9 min. 21 sec. Courtesy of Videobrasil Historical Archive

Addressing feminisms, gender roles, patriarchy, sexual normativity and ways of life that insist on affirming their difference, Virginia de Medeiros (b. 1973), in turn, subverts documentary strategies to go beyond testimony, reviewing ways of reading and representing reality and otherness. Cais do Corpo (2015), made during the “revitalization” of Rio de Janeiro’s port area for the 2016 Olympics, looks at the performativity of the body of sex workers as a social and political practice to confront an idea of urban modernization that ignores the human. In Sergio e Simone (2009), awarded at the 18th Videobrasil Contemporary Art Festival, the artist records the transition, after a crack overdose, of Simone, a transgender woman who lives in one of the most degraded areas of Salvador, into Sérgio, a cis man who considers himself sent by God to save humanity.

Portrait of Clara Ianni, © Photo: Videobrasil Historical Archive

Clara Ianni, Forma Livre, 2013, video installation, 7 min. 14 sec. Courtesy of Videobrasil Historical Archive

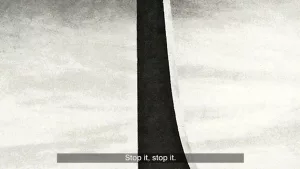

Clara Ianni, Do figurativismo ao abstracionismo, 2017, video, 6 min. 15 sec. Courtesy of Videobrasil Historical Archive

The perception of time, history and space in the context of globalized capitalism and decolonial studies, another keynote of artistic production in the 2010s, finally has a peculiar representative in Clara Ianni (b. 1987). Moving between video, installation, objects and site-specific work, the artist creates devices to question hegemonic historical discourses, examine the relationships between art, ideology and history, and propose alternative modes of political imagination. The works shown at the Videobrasil biennials are examples of this project. Do figurativismo ao abstracionismo (2017), drawing from Ianni’s research in the archives of the São Paulo Biennial Foundation, looks at the dynamics between the institutionalisation of Brazilian modern art and the country’s colonial past. In turn, Forma livre (2013) evokes the massacre of workers during a riot against the inhumane working conditions in the construction of Brasília in 1959, linking the discourse of architectural modernity in Brazil with the persistence of archaic social and political relations.

Together these artists and works offer a powerful overview of the unique strength of video in the Brazilian contexts — particularly as a medium for dissident, experimental and politically engaged practices led by women.

Paulo Herkenhoff, “Imemorial, de Rosângela Renno”, in Invenção de mundos: coleção Marcantonio Vilaça, ed. Moacir dos Anjos (Recife: Instituto Cultural Banco Real, 2006), pp. 174–175.

2

https://site.videobrasil.org.br/acervo/artistas/obras/39686

3

Jochen Volz, Writings for Cinthia Marcelle (São Paulo: Galpão Videobrasil, 2016), p. 9.

Solange Oliveira Farkas

Founder and artistic director of Associação Cultural Videobrasil, an institution responsible for maintaining an extensive video art collection on the Global South’s production and for organising contemporary art events with international partnerships. Farkas has been the artistic director of the Biennial Sesc Videobrasil since 1983 and is a member of the International Biennial Association’s board. In 2017 she was honoured with the Montblanc Arts Patronage Award, and in 2004 with the Sergio Motta Award. Over the last four decades, she has curated exhibitions, festivals and biennials in several countries – including Indonesia, Portugal, Russia, South Korea and the United Arab Emirates – and served on award committees for art events and cultural institutions all over the world.

Solange Oliveira Farkas, "From Pioneers to the Present: The Political Force of Brazilian Video Art." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/des-pionnieres-a-nos-jours-la-puissance-politique-de-lart-video-bresilien/. Accessed 25 February 2026