Research

Students of the Institute of Fine Arts in Warsaw, where Resia Schor (sitting on a chair on the right) prepared for exams at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw in 1929, black and white photography, photo courtesy of Mira Schor

When the artistic field in Warsaw revived after the First World War, women sought to be a part of it. Mary Litauer (1900–1992), Bella Natanson (1902–?) and Resia Schor (1910–2006) had different backgrounds but shared the ambition to become an artist. Each of these women adopted a different strategy to achieve her goal, navigating the interwar artistic sphere of Warsaw in distinctive ways. The decisions they made, including whether to engage with the Jewish artistic world or distance themselves from it, were encumbered by their life circumstances and socio-economic backgrounds.

The First World War was a turning point in women’s social and political situation. In 1918, women in the Second Polish Republic gained the right to vote. Gradually, more of them began taking up employment and pursuing higher education. Artistic studies were especially popular amongst young women, who, in the case of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, made up around 45% of the candidates applying, around 10% of them Jewish1. However, equal legal rights did not amount to equal treatment. Women were absent from higher academic hierarchies, and were a minority amongst artists exhibiting their works.

M. Litauer, B. Natanson and R. Schor were part of a generation that, due to modernisation and the changes within Jewish society that had begun in the second half of the 19th century, had broader opportunities for education and for defining their own path. More girls were educated in public and private schools, which expanded their interests and opened them up to the world outside the Jewish diaspora2. This Polonised and acculturated generation existed within an increasingly hostile socio-political climate. During the 1930s, the political situation of Jews worsened, and antisemitism increased.

Portrait of Mary Litauer, 1923, black and white photography, Archive of the Academy of Fine Arts, Warsaw

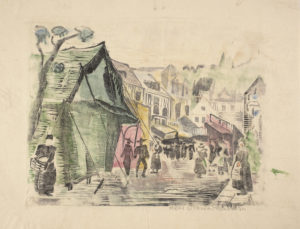

Mary Litauer, Pejzaż z kuźnią [Landscape with a smithy], unknown date, 16.1 x 20.7 cm, colour woodcut on paper, National Museum in Warsaw

Mary Litauer, Uliczka w Markach [Street in Marki], unknown date, 19.5 x 25.4 cm, colour woodcut on paper, National Museum in Warsaw

Mary Litauer’s application to the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw dates to 19233. The submitted photograph gives a glimpse into the young woman’s status, showing her wearing a lavish fur coat and an elegant fringe-trimmed hat. She was born in 1900 in Vilnius into an assimilated Jewish family, affluent and modern enough to support their daughter’s pursuit of artistic education. By the age of 23, she had already gained experience significant in her artistic growth, including travelling to Berlin to study under Alexander Archipenko (1887–1964). At the Warsaw Academy, she requested to be moved to the studio of Tadeusz Pruszkowski (1888–1942), whose students held a privileged position within the academy. His studio birthed artistic groups, such as the Brotherhood of St. Luke [Bractwo Świętego Łukasza], which had garnered interest and obtained professional opportunities since the late 1920s. M. Litauer did not have access to the same opportunities. The Brotherhood consisted solely of male artists who drew from the Christian tradition. And so M. Litauer, together with two other Jewish students, Gizela Hufnaglowna (1903–1997) and Elzbieta Hirszberzanka (1899–?), decided to start a group of their own. In 1929, they established Colour – most likely the only women’s artistic group in interwar Poland. They asserted their autonomy while supporting each other in finding a footing in the Polish artistic field. They faced discrimination, proof of which can be found in the fact that they were excluded from a meeting of the Union of Art Associations. In the following years they exhibited their works at the Trade Union of Polish Artists and Designers (1929), Czesław Garliński’s Salon (1930) and the Art Propaganda Institute (1931, 1933), all of which were Polish galleries. The artists depicted primarily universal subjects – such as still lifes, landscapes. M. Litauer focused on scenes from the town of Kazimierz Dolny and her home town of Vilnius. She rarely incorporated imagery specific to Jewish culture into her works, the undated painting Tashlikh being a rare example. After the termination of the group in 1933, M. Litauer continued her solo career, and took part in Polish and international exhibitions. In 1935, she married architect Roman Schneider. She spent the war years in exile and joined the Polish Armed Forces. Eventually, in 1950 the couple settled in Toronto, Canada, where M. Litauer continued her artistic practice.

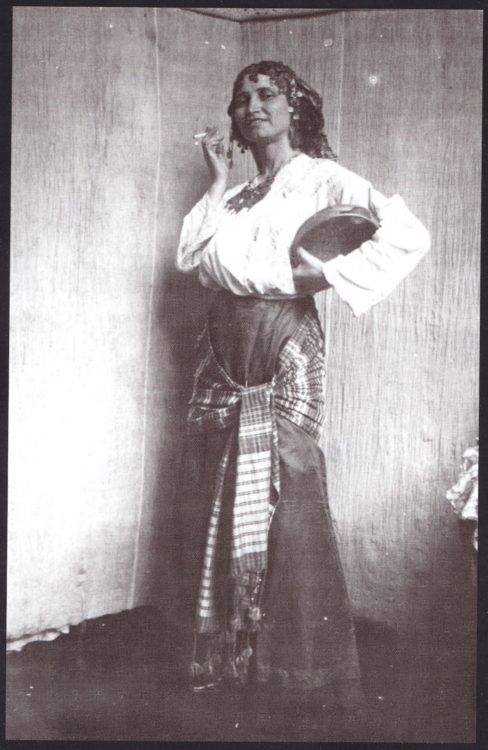

Portrait of Bella Natanson, 1935, black and white photography, Archive of the Academy of Fine Arts, Warsaw

Spring Jewish Art Ball in Bristol, in Nasz Przegląd Ilustrowany, April 10, 1932, p. 5, Bella Natanson is depicted in the right photo, third woman from the left, standing

Bella Natanson was born in Russia in 19024. Little is known about her early life, apart from the information supplied in her student application: she spoke Russian, Polish, French and German; her father was an entrepreneur; she studied natural sciences at a university in Russia. Those facts indicate that she most likely came from a wealthy family which cared about their daughter’s education. In Russia, she married J. Natanson, a lawyer. The couple moved to Warsaw, where they began to participate in Jewish artistic life, mainly as members of the Jewish Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts. In the early 1930s, her involvement was that of an art lover and patron. Like other wives of influential Jewish people, she became part of the Lady Committee, organising balls and engaging in philanthropy. In a photo published in the Nasz Przegląd newspaper in 1932, we see her at the Spring Jewish Art Ball, standing amongst other members of the Committee5. Wearing all black, with unruly hair and no jewellery, she stands out from the other lavishly presented, meticulously dressed women. In 1935, after her husband’s death in a car crash, she applied to the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. She had undertaken no preparation, and had been learning art under her own auspices for the past year. She was rejected, but continued to develop her skills, took advantage of her established position within the Society and began presenting her paintings at the organisation’s exhibitions between 1935 and 1939. In the second half of the 1930s, she joined the Board of the Jewish Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts, becoming the only woman to hold this position. Though her career was closely linked with the organisation, she managed to expand beyond its circle. In October 1937, she had a two-artist exhibition with Józef Śliwniak (1899–1942) in C. Garliński’s Salon, a reputable gallery, where she presented 28 oil paintings, mostly landscapes and still lifes with flowers. Information about her life after the war is sparse: she most likely survived and moved abroad.

Portrait of Resia Schor, 1930, black and white photography, Archive of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw

Resia Schor, Kobieta z kwiatami [Woman with flowers, portrait of the artist’s mother], 1937, aquatint, 18 x 14 cm, reprint from the newspaper Nasz Przegląd Ilustrowany, February 7, 1937, p. 6

Resia Schor (née Ajnsztajn), born in 1910 in Leczna near Lublin, had a less advantaged background6. She came from a rather indigent, strictly observant Jewish family. Her ambitions of pursuing an artistic education were not in line with what was expected of a girl from her milieu. However, thanks to her determination and her mother’s support, she moved to Warsaw and applied to the Academy of Fine Arts in 1930. She wrote in her resume: “Since I was born, I have had a talent for painting, and it is the field of art to which I wish to devote myself”. She was accepted and began studying painting at T. Pruszkowski’s studio.

She differed from the majority of Jewish women students at the Academy at that time, most of whom came from wealthy, Polonised families. Year after year she had troubles covering the tuition fees, and in 1933 she got into debt to pay for her studies. Financial issues may be one of the reasons why she moved away from painting, though her talent was recognised and, in 1932, awarded a prize at an exhibition of T. Pruszkowski’s studio. In the following years, she devoted herself mostly to graphic art and experimented with woodcuts, aquatints and lithography. This shift in her artistic practice presented her with income opportunities. Between 1937 and 1939, she participated in the project “Graphic Works for Our Readers” organised by the Nasz Przegląd newspaper as a way of supporting young Jewish artists and promoting Jewish art. Copies of works printed in the newspaper were available to buy for an affordable sum of ten zlotys. R. Schor began to gain some recognition for her graphic works, and was mentioned in an article on “Jewish Graphic Arts” in 19387. She created landscapes and portraits, genres common amongst students of the Academy. In doing so, she picked subjects that drew that from her early-life experiences: scenes from life in a village and images of loved ones, adding an intimate quality to her works. Before the war, she moved to Paris, where she married artist Ilya Schor (1904–1961). The couple fled to New York in 1941. In the following years, she devoted herself to family life. After her husband’s death, initially to support her family, she returned to art, creating silver jewellery, mezuzahs and eventually large-scale mixed-media objects that incorporated painting.

Each of the three artists was similarly disadvantaged as a Jewish woman in interwar Warsaw. They had different opportunities when entering the artistic field due to their disparate social and financial statuses. Each took a different approach to shaping their careers. M. Litauer steered her artistic education and career with awareness, mostly distancing herself from the Jewish artistic field. B. Natanson, on the other hand, developed her career within it, taking advantage of existing connections. R. Schor was forced to compromise in her choices and take financial issues into account. What connected them was their identity as Jewish women, making them twice as vulnerable to exclusion. Their paths, though distinctive, share similarities – their emerging careers in Warsaw cut short by the war, forcing them to start anew outside the country.

Archive of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, Collection of files from before September 1939. Documents later mentioned in this article come from this resource.

2

Renata Piątkowska, “A Shared Space. Jewish Students at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts (1923–1939)” in Art in Jewish Society, ed. Jerzy Malinowski, Renata Piątkowska, Małgorzata Stolarska-Fronia, Tamara Sztyma (Warsaw-Toruń: Polish Institute of World Art Studies & Tako Publishing House, 2016), 17.

3

Biographical information on Mary Litauer comes from the following resources: Archive of the Academy of Fine Arts, student file no. 773; Renata Piątkowska. “Malarki warszawskiej grupy « Kolor »”, Aspiracje (Autumn 2009): 2–9; Joanna Sosnowska. Materiały do dziejów Instytutu Propagandy Sztuki (1930-1939) (Warsaw: Instytut Sztuki Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 1992); Jola Gola, Maryla Sitkowska, Agnieszka Szewczyk, ed., Sztuka Wszędzie. Akademia Sztuk Pięknych w Warszawie 1904–1944, exh. cat., National Gallery of Art., Zachęta, 8 June–August 26, 2021 (Warsaw: Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, Zachęta – National Gallery of Art, 2012). Marika Kuźmicz. Z Wilna do Warszawy. Przez Teheran do Toronto. Historia Mary Schneider lecture, 11 November 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=riYD_tuLbWA.

4

Biographical information on Bella Natanson comes from the following resources: Archive of the Academy of Fine Arts, student file no. 927; Hanna Garlińska-Zembrzuska, Działalność wystawowa Salonu Czesława Garlińskiego w latach 1922–1939 (Wroclaw: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich / Wydawnictwo Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 1963); Jerzy Malinowski, Malarstwo i rzeźba Żydów Polskich w XIX I XX wieku (Warsaw: PWN, 2000); Renata Piątkowska, “Artystki i miłośniczki sztuki – kobiety w żydowskim życiu artystycznym międzywojennej Warszawy. W kręgu Żydowskiego Towarzystwa Krzewienia Sztuk Pięknych”, Studia Judaica, no. 1, (2021): 175–211; Małgorzata Biernacka, Katarzyna Mikocka-Rachubowa, ed., Słownik artystów polskich i obcych w Polsce działających : malarze, rzeźbiarze, graficy, vol. 6 (Wroclaw: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich – Wydawnictwo Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 1998).

5

“Spring Art Ball in « Bristol »” Nasz Przegląd Ilustrowany, 10 April 1932, p. 5.

6

Biographical information on Resia Ajnsztajn comes from the following resources: Archive of the Academy of Fine Arts, student file no. 1; Archive of Ilya Schor and Resia Schor. Courtesy of Mira Schor; Nasz Przegląd Ilustrowany newspaper. See also: Mira Schor (ed.), Abstract Marriage, Sculpture by Ilya Schor and Resia Schor, exh. cat., Provincetown Art Association and Museum, Provincetown, 16 August–29 September, 2013 (Provincetown: Provincetown Art Association and Museum, 2013) or listen to a podcast interview with Mira Schor https://radiokapital.pl/shows/kocham-w-zyciu-trzy-rzeczy/2-resia-schor/.

7

Adam Herszaft, “Grafika żydowska”, Nasz Przegląd, 1 May, 1938, p. 16.

Katarzyna Ewa Trzeciak is a PhD student at the University of Warsaw, Poland where she conducts research on Jewish women students at the Academies of Fine Arts in Warsaw and Krakow during the interwar period. Her master’s thesis examined the work of Resia Schor. She is the co-curator of the exhibition Three Things I Love in Life – The Car, Liquor and Sailors. Untold Stories of Women Students of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, 1918–1939 (lokal_30 gallery, Warsaw, 18 June–15 September 2021).

An article produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring.

Katarzyna Ewa Trzeciak, "How to Become an Artist in Interwar Warsaw. Examining the Emerging Artistic Careers of Three Jewish Women: Mary Litauer, Bella Natanson and Resia Schor." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/devenir-artiste-dans-la-varsovie-de-lentre-deux-guerres-enquete-sur-les-debuts-artistiques-de-trois-femmes-juives-mary-litauer-bella-natanson-et-resia-schor/. Accessed 8 July 2025