Research

Screen capture of early beta prototype GEnder Research Tool (GERT), (2018–2019) showing exhibition locations on world map (created by Simon Low)

In 2019, my collaborators and I convened a symposium on “Art, Digitality and Canon-making” as part of the Gender in Southeast Asian Art Histories programme inaugurated in 2017.1 Keen to explore relationships between artists and art, and the larger Southeast Asian cultural constructs of gender as enacted in political, economic and religious domains, we were also open to the notion of digitality as shaping and impacting the discipline of Art History methodologically.2 However, we were unsure of its methodological significance – for none of us were digital humanities scholars. Yet there was a nagging sense that the old ways weren’t quite working, and perhaps, it might be generative to think outside of the box, to solicit new partnerships with adjacent fields.

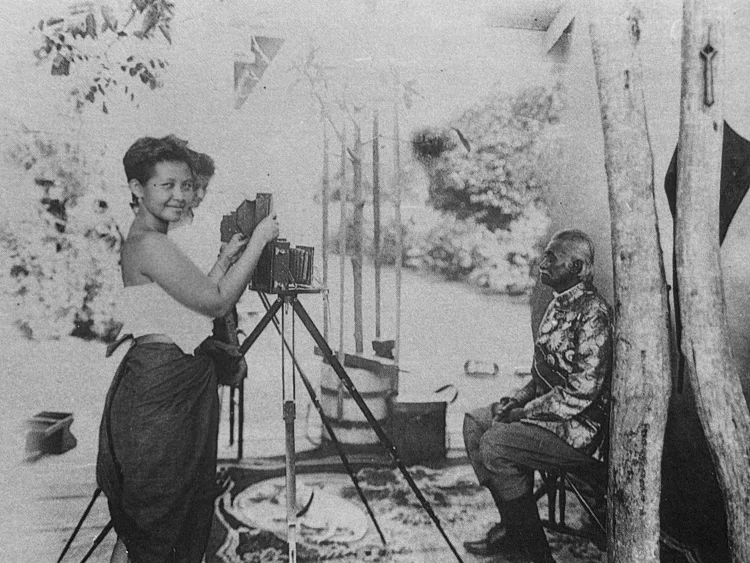

Often, gender disparity and women’s absence in the arts have been the strongest point of contention in the context of Southeast Asian feminist art scholarship. For example, the recent increase in nation-centric, women-centred exhibitions and monographs emerging from Southeast Asia in the last two or so decades all aimed to revise male-centred/male-dominated narratives; they served as unapologetic attempts to interrogate the canon for a more inclusive art history of the region. Indonesian Women Artists: When the Curtains Open (2007), which accompanied the women’s show at the National Gallery of Indonesia, surveyed 34 prominent “forgotten” women artists.3 In spite of the many good reasons for treating women as a separate group, this approach has been criticised predominantly for not adequately combating the larger issue of male-defined canonicity, and the implicit structural inequalities that continue to persist within the institutions and the discipline of art history. Pulling women out into a separate chapter, a separate exhibition, a separate book has been criticised as counter-productive and patronising.4

In my own research dealing with women’s absence from art history and exhibition history, I have come to realise that the problem beyond the common conditions that they share is also one that is rooted in practicalities. In light of the politics of canon-making cautioned by many, how do we fill the gap, fix the problem of structural inequalities – and do so without women-centred discourses becoming tokenistic gestures, and their histories merely compensatory? In short, how can we include everyone? This idea, simple and unassuming, refused to go away – over lunches with Marni Williams, a colleague working in art publishing who had herself been mulling over more democratic ways of disseminating information, this idea of creating an open-access database for women artists germinated and grew.

Historians have long enlisted digital tools in their work – and in particular feminist art historians have found immense potential in remapping the terrain not just to “add” knowledge but to critically transform the way such knowledge is deployed.5 The early 1990s, with the advent of the World Wide Web, saw the pioneering of scholarly digital projects on women’s histories such as The Women Writers Project.6

In the year that followed, I enlisted the in-kind support of my retired software engineer father to create a prototype for me. I toyed with the idea of using digital technology to neutralise the canon by empowering everyone – everyone with internet access that is. My concept of a digital platform for women-centred discourses was quite a practical solution to those wanting to develop women-only exhibitions and texts but faced the dilemma of having to determine who gets to stay and who does not. No longer limited by the floor space of an institution or gallery, or by the number of pages in a book, the recovery of women artists can now take place on a digital platform in the form of an editable database similar to Wikipedia, with the added function of enabling geographical and temporal mapping. One might therefore think of it as a quasi-Wiki-Neatline.7 Theoretically this digital platform would directly address the implicit issue of structural inequalities that women-centred exhibitions and texts inevitably inherit. It would unsettle the canon-making process, with the potential to now redistribute the power of gatekeepers to internet users, and to acquire and accumulate knowledge in a non-hierarchical system.

By 2019, the prototype was ready and I presented my paper.8 As proof-of-concept, I had extracted biographic data from the book Indonesian Women Artists. I created a profile of each of the 34 artists across fields that can be made compatible with existing APIs supplied by museums across the world. The fields included their country of birth, educational background, key instructors or mentors if known, the solo and group exhibitions they took part in, where their work is collected, associations that they were a part of, awards or accolades received, writings published about them as well and works that did not fall strictly within the domain of visual culture (Fig. 1). These fields may expand, given the malleability of the system.

Fig. 1: Screen capture of early beta prototype (2018–2019) showing biographic fields (created by Simon Low)

By extrapolating biographical information from physical texts into dynamic key fields, this digital platform enables the creation of a series of structured metadata that is in turn available for a range of computational processing, namely search, querying and report generation. There is immense value in developing structured datasets because they are no longer static but have become dynamic and can be manipulated for a whole range of purposes: visualised into charts, exported into other databases for comparisons and so forth. Once global addresses are assigned to the artist’s place of birth and their exhibitions, the locations could be visualised using Google Maps, offering immense capacity for comparative analysis and the potential for new research directions (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Screen capture of early beta prototype (2018–2019) showing exhibition locations on world map (created by Simon Low)

Far from disputing the value of women-centred survey books such as Indonesian Women Artists which has offered critical perspectives on the female artist’s practice and art, I demonstrated how such works are nonetheless flawed because of their format. In textual (analogue) form, these are attempts to ‘profile’ the artist are ultimately doomed to incompleteness (we must remember that, for the artists who are still alive, their lives and practice continue to evolve) – a book’s failure is therefore not that of putting them on a pedestal, but of immortalising them and packaging them into a time capsule. In digital form – not merely digitalised form – the limitations of the book format can be circumvented, and its canonicity reconfigured. By tapping into the malleable structure of a digital platform, it is possible to create a more inclusive and expansive environment for the recovery of women’s work. Crucially, it will have the capacity to support an infinitely expandable list of women artists – and more.

On the prototype which was centred on limited data (for just 34 artists), I could only outline a future version of the platform and its capability to become like other digital humanities projects for art historians, where it might be possible to harness the computational, statistical and informational capability of digital technology and thus to advance the field of women’s histories and feminist art history. In this instance, the aim of building a digital platform as a foundation for efforts to recover women artists in Southeast Asia is not merely a matter of digitising materials in order to enable greater access to them – in other words, it is not just a new way of doing old work a little faster. The objective here is to use digital methods to reconfigure our fundamental understanding of the practice of a professional artist, and to ask new research questions. Search results from querying serve as a starting point, rather than an endpoint, and have the potential to provoke analysis or research directions.

The most compelling aspect is that a woman’s entry on the digital platform is not determined by how widely she has exhibited or how extensively her work has been collected – which has often been the criterion for inclusion in survey texts or exhibitions. Equally important and interesting questions can be raised about the type of exhibitions (local markets, regional art fairs, international biennales) as well as non-activity, such as long gaps of absence from the global or local scene. Large-scale patterns become evident through data mining, and it is now possible to look at, if not for, trends across a geographical or temporal span. This is all possible through the benefits of computational processes, something that would not be possible in analogue format. If we were to pursue this – going beyond the 34 artist’s profiles to far more – then the kinds of patterns or information gleaned from such data would surely be nothing short of fascinating.

Of course nobody offered the required funding on the day I presented my paper – but this prototype and the idea did receive the support of like-minded individuals, key amongst them being the colleague I had first discussed this bizarre idea with from the beginning. Many nights of grant-writing and Zoom meetings with Marni and the development team later, a working prototype of the Artists Trajectory Map (ArTM) (Fig. 3 and 4) was finally completed in July 2023.9 It may have evolved from being a women-centred digital database and platform to one that now enables the broad study of artists’ professional trajectories by aggregating, mapping and visualising biographic and exhibition data, but it is ultimately underpinned by feminist aims and still offers the capacity to support gender-centred perspectives.

Fig. 3 Screen capture of an example of an artist profile on ArTM (2022)

Fig. 4: Screen capture of geo-temporal visualization of art exhibitions by an artist (2022)

In the course of developing the tool, I found it to also be a powerful teaching resource – especially for provoking analysis and opening new research directions. For example, students may play with existing datasets to help identify patterns and gaps in research, and in the process learn to develop and design research questions about artistic (or gendered) networks, collection records, exhibition histories and market trends, amongst others. Having now recognised its potential to reap significant pedagogical benefits, I am embarking on a new project reframing and evolving ArTM into a teaching tool for the research and engagement of collections in the Southeast Asian region with university museums. What I have learned from this process is that feminism and digitalism can come together to empower users of the platform to engender fresh perspectives about male and female artists. And perhaps that bizarre ideas too may sometimes lead to new ways of telling stories.

Entitled, “Gender in Southeast Asian Art Histories II: Art, Digitality and Canon-making?” this symposium is part of a two-tier yearlong series of workshops and panel discussions on gender and sexual difference in the studies of art history and related fields, jointly hosted by University of Chulalongkorn and University of Sydney. The organisers included Yvonne Low, Roger Nelson and Clare Veal, in partnership with Juthamas Tangsantikul (Chulalongkorn University) and Catriona Moore (University of Sydney). The first Gender in Southeast Asian Art Histories symposium took place in 2017 and was organised by Yvonne Low, Roger Nelson, Clare Veal and Stephen Whiteman.

2

Klinke, Harald. “The Digital Transformation of Art History”, in Kathryn Brown (ed.), The Routledge Companion to Digital Humanities and Art History (New York: Routledge, 2020) 32-42.

3

Bianpoen, Carla, Wardani, Farah and Dirgantoro, Wulan. Indonesian women artists: The curtain opens. (Jakarta: Yayasan Senirupa Indonesia, 2007). The book was launched in conjunction with a groundbreaking exhibition, Intimate distance: Exploring traces of feminism in Indonesian Contemporary Art, curated by the same authors. Held at the National Gallery of Jakarta in August 2007, the exhibition aimed to examine traces of feminism in women’s art and the strategies employed by the artists.

4

See for example Susan Best’s critical and nuanced appraisal of the exhibition, Contemporary Australia: Women, in 2012 outlines its critics (i.e. that the all-woman show was seen as ‘an insulting anachronism’). “What is a feminist exhibition? Considering Contemporary Australia: Women”, Journal of Australian Studies, 2016, 40:2, 190-202.

5

As Johanna Drucker puts it, ‘only a combination of dramatic proof-of-concept works and strategic funding and hiring initiatives will change the field’. “Is there a ‘digital’ art history?”, Visual Resources, 2013, 29: 1-2, 5-13. See also Kathryn Brown and Elspeth Mitchell, “Feminist Digital Art History”, in ed. Kathryn Brown, The Routledge Companion to Digital Humanities and Art History (New York: Routledge, 2020) 43-57.

6

See, for example, Howe, Tonya L. (2017) “WWABD? Intersectional Futures in Digital History,” in ABO: Interactive Journal for Women in the Arts, 1640-1830: Vol. 7: Iss. 2 , Article 4.

7

Neatline is a geotemporal exhibit-builder that allows you to create visually appealing complex maps, image annotations, and narrative sequences from Omeka collections of archives and artifacts (see examples in https://neatline.org/about/). I first learned about this when my proposal on mapping Singapore biennales was selected and I was accepted to participate in a workshop on Digital Art History, Visualising Venice: The Biennale and the City, organised by Duke University and Venice International University in 2015.

8

Low, Yvonne. “Unmaking the Canon? ‘Indonesian women artists’ in the Future (Archive)”, at Gender in Southeast Asian Art Histories II: Art, Digitality and Canon-making?, 18 October 2019, University of Sydney (Unpublished Conference proceedings).

9

Marni Williams, who is completing her PhD in Digital Humanities, and I received a University of Sydney FASS External Engagement Fund for developing Artists Trajectory Map (ArTM) with Systemik Solutions in 2022. This was developed alongside a Power Institute digital publishing project led by Williams that I was also involved in. Please contact [email protected] to explore the prototype of the Artists Trajectory Map (ArTM).

Yvonne Low teaches subjects in modern and contemporary art, gender and sexuality in Asian art histories and art curation in the undergraduate and postgraduate programmes at the University of Sydney. Her research looks at Southeast Asian art and Chinese diaspora cultures, specialising in women’s practice and artistic networks. Her writings and projects have addressed canonical art histories using decolonial, feminist and digital methodologies. She is committed to advancing scholarship in the region as the part of the editorial committee of Southeast of Now Journal.

Acknowledgements: The author wishes to extend her special thanks to her father for believing in her and for creating the first prototype, Emeritus Prof John Clark for encouraging her to pursue it after the conference, her co-convenors Clare Veal and Roger Nelson for brainstorming together the name GEnder Research Tool (GERT). Artists Trajectories Map (ArTM) version 1 is developed in partnership with Marni Williams (Power Institute) and the Systemik Solutions team (Ian McCrabb, Isobel Andrews, Mufeng Nui).

Southeast Asian Women Artists

Yvonne Low, "From Feminism to Digitalism: Empowering women, engendering new stories." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/du-feminisme-au-champ-numerique-donner-le-pouvoir-aux-femmes-generer-de-nouvelles-histoires/. Accessed 22 February 2026