Research

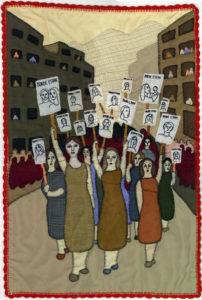

Gran marcha de mujeres diciendo no más porque somos más, Fondo Isabel Morel, colección Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos

This is the story of not one, but many women who, in shared anonymity, chose to testify against a both neoliberal and patriarchal power. They are the arpilleristas, Chilean women and weavers, authors of subversive histories written with the help of the needle and thread. Already reused and enhanced in the 1960s by the Chilean artist Violeta Parra (1917–1967), this ancient artisanal tradition of arpilleras1 transformed itself into a spontaneous strategy of civil disobedience throughout Chile’s military dictatorship (1973–1990). Some arpilleras subsequently migrated to various parts of the world with the wave of exiles, activating the deployment of an international solidarity network with the Chilean cause. This article aims to make visible the role of these women in the fight against domination, as well as the past and present value of these dissident objects on the border of art and craft, shedding light on the necessity to observe once again the relationship between artistic production and the historical and political context in which it is manifested.

Acts of love and resistance

“With word and deed we insert ourselves into the human world.”2

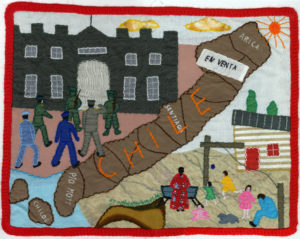

Chile en venta [Chile on sale], Fondo Isabel Morel, colección Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos

The date of 11 September 1973 marked a crucial moment in the history of Chile: General Augusto Pinochet took power, establishing a military dictatorship that dominated the country for seventeen consecutive years. This date thus signified the suppression of all individual rights and of any political and social activity other than that imposed by the regime, as well as the inception of unprecedented institutional violence. In the context of this real and symbolic violence based on total control of society, the presence of women was not secondary. Their presence was the vehicle for a profound radicalism in action and reparation of a fractured identity, otherness, and cultural memory. Chilean human rights activist Isabel Morel Letelier argues that the military dictatorship came to accompany the ordinary and habitual patriarchy. In this sense, this military coup took on a gendered dimension. Firstly, the subsequent political and economic disarticulation predominantly concerned the social classes active under the Unidad Popular government (Popular Unity, 1970–1973) amongst them the left-wing militants and leaders, unions, professional associations and localities, of which the majority was largely male. Secondly, women were kept in their traditional role to ensure that, “By praising their spiritual values and placing them above their daily needs, they were distanced from the public, masculine sphere and the eventual desire to participate, becoming totally excluded from decision-making arenas.”3

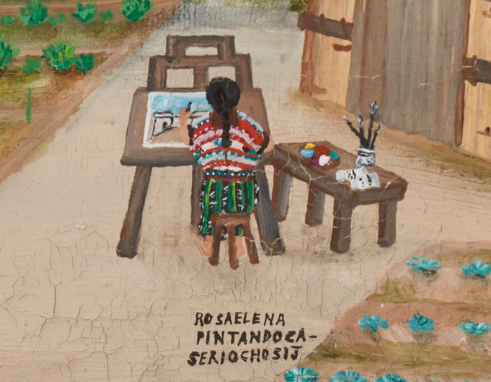

Marcha de mujeres de familiares de detenidos desaparecidos [March of women of relatives of disappeared detainees], Fondo Isabel Morel, colección Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos

Throughout this undemocratic transition, the integrity of the pobladora (woman living in a slum or poor neighbourhood), generally willing to take care of her family, was disrupted by mass arrests and the disappearance of family members. As the domestic triad mother-wife-woman disappeared, the pobladora became aware of the role she could play in the transformation of society. As Lisa Baldez stated, “The recession thrust many working-class families below the poverty line and forced women to find alternative ways to provide for their families.”4

During this crisis, community initiatives, such as manual training courses, were born under the protective wing of the Church, becoming the first genuine forms of resistance and emancipation. The main, if not only, organisation involved was the Agrupación de Familiares de Detenidos Desaparecidos (Association of Relatives of Disappeared Detainees), created in 1973 with the help of the Comité de Cooperación para la Paz en Chile (Committee of Cooperation for Peace in Chile), later dissolved and replaced by the Vicaría de la Solidaridad (Vicariate of Solidarity) in 1976. Through oral narratives we have discovered that the arpilleras workshops were proposed by artist Valentina Bonne, inspired by mola (an aboriginal craft developed by women of the indigenous gunadule communities of Colombia and Panama) and “another foreign fashion”– patchwork.5 The first arpilleras workshop opened in March 1974.

Could these women speak? Marginalised both by the economy and the ideology of a dominant gender, how did they treat the mutism rooted in their bodies? To reconstruct these voiceless beings, the arpilleristas first had to experience self-awareness, where a double acknowledgement took place: that of the self, the “ser-hacer mujer”6, as an active political subject, and of the relationship between the self and its surroundings, implying the release of domestic invisibility in order to establish oneself in the public sphere as a new initium, ready for action.7

Rewriting the limits of the possible

Aunque corten la libertad, seguiremos adelante [Even if they cut freedom, we will move forward], Fondo Beatriz Brikkmann, colección Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos

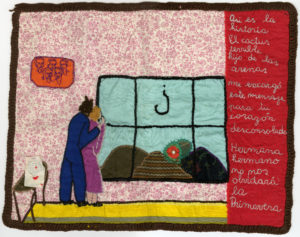

Asi es la historia [This is the story], Fondo Carmen Waugh, colección Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos

The origins of the arpilleras can be traced back to Violeta Parra’s wool embroideries from the 1960s “where on large canvases or natural and coloured burlap, she embroidered images of vivid wool” that illustrated the daily life of her people.8 It seems that thanks to her, the embroideries executed by the female fishermen of the Isla Negra were discovered and deeply admired by Pablo Neruda, who celebrated them in a chapter of his book Para Nacer He Nacido (1978). Like those that preceded them, the arpilleras made after the military coup presented a character of community and solidarity, and expressed the life of their authors. However, their technique was different – they were no longer only of embroidered wool but rather of recovered and appliqué fabrics. As for the content, their vindictive and denunciatory force set them apart them from the colourful and cheerful representations of the earlier arpilleras.

Brought together in the studios coordinated by the Vicaría de la Solidaridad, each woman devoted herself to an arpillera. Spaces of exchange and mutual solidarity against oblivion were created, in which each voice, story and emotion resonated with one another, regaining the strength of a memory that revealed itself in the final creation. Coloured threads mixed with various scraps of fabric on canvases made of bags of flour, potatoes and sugar, created true images of the social, political and economic (Chile en Venta, 1973–1990) reality filtered through the imagination of the arpilleristas. The internal organisation of each workshop guaranteed the sale and diffusion of the arpilleras, as well as the redistribution of profits to their creators, a percentage of which was reinvested in the workshops so they could continue to exist.

Yet the fate of these works lies elsewhere, beyond the omnipresent mountain chain of the Chilean landscape. What differentiated them from the early embroideries revealing the talismanic power that these objects concealed is that “the arpilleras had an enormous impact on the national culture. The arpilleristas began to work during a period in which nobody dared reject authoritarian rule, a time of self-control and obedience. These women were among the first to create a culture of resistance.”9 They composed a social portrait of a marginality reduced without respite to silence through institutional denial.

Éxodo, 1973-1990, Fondo Isabel Morel, colección Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos

“Los Tapices de la difamación”, Segunda, 11 April 1978, periódicos de los fondos documentales – Sección periódicos de la Biblioteca Nacional de Chile

The first creations that corresponded to the phase of “solidarity construction”10 testified to human rights violations committed by the new regime. With time, the arpilleras began to highlight critical aspects of the precarity that affected daily life in Chile: notably health, unemployment, hunger and exile (Éxodo, 1973–1990).

Two major events confirmed the subversive strength of these objects, the first of which was the opening of the Galería de Arte Paulina Waugh in Santiago de Chile in 1975. In 1976, the gallerist Paulina Waugh financed a promotional project and the sale of the arpilleras produced by the Zona Orienta workshop. Three exhibitions were organised offering the chance for professional artists and arpilleristas to meet and interact. On 13 January 1977, the gallery – which had hosted two of the exhibitions – burnt down, likely at the hands of the Central Nacional de Informaciones (National Information Center). This event resulted in both the closing of the space and the loss of various arpilleras and works by Roberto Matta, Nemesio Antúnez and Eduardo Vilches, among others.11 The second fact relates to the discovery of the arpilleras outside of the national territory and at the point of crossing borders12. Many of these fabrics travelled with exiles and contributed to the activation of a transnational solidarity network to support the fight by the Chilean people. In migration, these embroidered writings escaped censorship and attained a global community, now aware of these crimes committed against humanity. Consequently, arpilleras were identified several times by the police and reported in the press as “Anti-Chilean”, “subversive propaganda,” and “tapestries of slander,” of which neither the “phantom” sender nor the addressee could be identified.

Para que nunca más en Chile [So that never again in Chile], Fondo Isabel Morel, colección Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos

In the deafening silence of this fascist culture of terror, these women, anonymous but animated by a profound desire for justice and truth, launched a movement opposed to that of the established system. This movement, associated with material culture at the service of social change – the arpilleras – still serves as a model in the fight against subjugation in favour of free speech, action and emancipation of all the men and women of the world. The past and present value of this “low art” rests not only in its physical appearance but also in the dissensus that it liberated, allowing a different temporality to blossom – a dissent that today draws attention to the unsaid constituting an antidote to the oblivion and the supremacy of a mono-narrative historical discourse that omits feminine, subordinate and marginal groups.

Roberta Garieri is a doctoral student in the History of Contemporary Art (Université Rennes 2). She is working on her dissertation, of which the working title is Chili hors du Chili : visibilité et réception des pratiques chiliennes dans la nouvelle géographie globale de l’art contemporain depuis 1973 (Chile out of Chile : visibilty and reception of Chilean practices in the new global geography of contemporary art since 1973). Interested in the rewriting of the real and symbolic dimension of Chilean artistic exile, she dedicates her research to problems resulting from globalised cultural transfers, as well as the relation between cultural production and its social and political context. She is a contributor to Hot Potatoes. Art, Politics, Exhibition Conditions, and Critique d’art. Actualité international de la littérature critique sur l’art contemporain.

The etymological sense of the word arpillera refers to a raw fabric used to “wrap products to protect them from dust,” see Joan Corominas and José Antonio Pascual, Diccionario Crítico Etimológico Castellano e Hispánico, Madrid, Editorial Gredos, 1980, p. 320-322, cited in Arpilleras. Colección del Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos, Santiago, Ocho Libros Editores, 2012, p. 10: « para empacar mercancías o cubrirlas del polvo » translation by the author.

2

English translation from Arendt Hannah, The Human Condition, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 1998, p. 176.

3

Valdés Teresa and Weinstein Marisa, Mujeres que Sueñan. Las Organizaciones de Pobladoras en Chile, 1973-1979, s. l., FLACSO, 1993, p. 76: « Al ensalzar sus valores “espirituales” por sobre sus necesidades cotidianas, se la extraía del ámbito público-masculino y sus eventuales deseos de participación y se la excluía totalmente de los espacios de decisión » translation by the author.

4

Baldez Lisa, Why Women Protest. Women’s Movements in Chile, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2002, p. 137.

5

Agosín Marjorie, Tapestries of Hope, Threads of Love. The Arpillera Movement in Chile, 1974-1994, Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press, 1996, p. 114.

6

Valdés Teresa and Weinstein Marisa, op. cit., p. 17 « being a woman ».

7

Arendt Hannah, op. cit., p. 129.

8

Violeta Parra, exhibition catalogue, musée des Arts décoratifs, Paris, 8 April–11 May 1964, Paris, musée des Arts décoratifs, 1964, p. 1.

9

Agosín Marjorie, op. cit., p. 25

10

Voionmaa Tanner Liisa, Arpillera Chilena. Compromiso y Neutralidad. Mirada sobre un Fenómeno Artístico en el Período 1973-1987, thesis in aesthetics, Santiago, Pontificia Universidad Católica, 1987, p. 37-38, cited in Arpilleras. Colección del Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos, op. cit., p. 12.

11

Arpilleras. Colección del Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos, op. cit., p. 74.

12

« Los Tapices de la Difamación », Segunda, 11 April 1978, p. 14-15 ; « La Propaganda Subversiva », La Tercera, 16 April 1980, p. 60 ; « La Propaganda Subversiva », La Tercera, 17 April 1980, p. 7.

Roberta Garieri, "Writings of subversion: the Chiliean arpilleristas." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/ecritures-de-la-subversion-les-arpilleristas-chiliennes/. Accessed 19 April 2024