Interviews

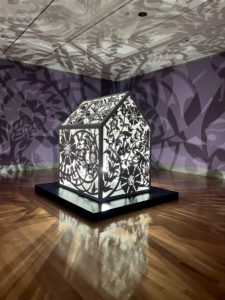

Anila Quayyum Agha, Liminal Space, 2021, acier lacquered steel, LED lamps, 65 x 65 in / 165.1 x 165.1 cm, installation view, A Beautiful Despair, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Forth Worth, 2021 © Courtesy Anila Quayyum Agha

This interview took place in the framework of the exhibition Re-Orientations: Europe and Islamic Art, from 1851 to Today held at the Kunsthaus Zürich from 24 March to 16 July 2023, which focused on the impact which the heritage of Islamic arts has had on Western fine and applied arts and cultural interactions between Europe and the Middle East.1 For this show, the artist Anila Quayyum Agha created a site-specific large-scale immersive installation featuring an interplay between pattern, ornament, colour, and light. Born in Lahore and based in the United States, she expresses her deep concerns regarding craft, gender, and environmental issues, as well as her vision of the relationship between East and West.

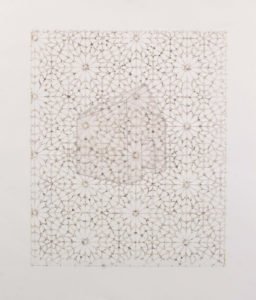

Anila Quayyum Agha, Antique Lace 1 (detail), 2016, mixed media on paper, laser-cut patterns on paper with mylar, embroidery and beads, 30 x 22 in / 76.2 x 55.88 cm © Courtesy Anila Quayyum Agha

Anila Quayyum Agha, Winged Shadows, 2019, mixed media on paper, steel dust, charcoal, wax, embroidery, 63 x 59 in / 160.02 x 149.86 cm © Courtesy Anila Quayyum Agha

Nadia Radwan: How did the experience of growing up and being trained in Lahore, Pakistan, before moving to the United States impact your practice as an artist?

Anila Quayyum Agha: When I was living in Pakistan, my dream was to become a painter, but my mother was concerned I wouldn’t have an income as an artist. She wanted me to be independent in Pakistan’s patriarchal system. So I studied textile design, which benefited me in my future endeavours. I gained an understanding of pattern and familiarity with the motifs and patterning created in various regions of South Asia. Once I moved to the United States and enrolled in graduate school, I was already adept at working with pattern and colour. But instead of being valued, my skills in surface decoration received much criticism as pattern was considered feminine, craftlike, and thus unimportant. There was a consistent negation of beauty and in turn a negation of cultures from the East which use pattern as an integral concept within the fine arts. I was taken aback by the West’s limited knowledge and exoticising of the East with its entwined ornamental influences and the histories of art and architecture in Islamic regions.

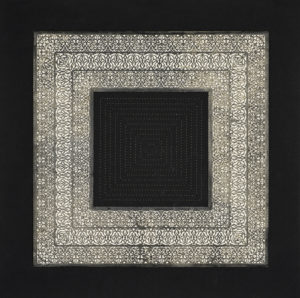

Anila Quayyum Agha, Black Tinted Flower, 2020, mixed media on paper, paper cutout, pastels, encaustic wax, silver embroidery, 30 x 30 in / 76.2 x 76.2 cm © Courtesy Anila Quayyum Agha

Anila Quayyum Agha, My Secret Garden, 2023, laser cut polished stainless steel, 48 x 48 in / 121.92 x 121.92 cm, installation view, New Worlds: Georgia Women to Watch, Atlanta Contemporary, Atlanta, 2023, photo: Kenyatta Stanchez © Courtesy Anila Quayyum Agha

NR: Despite pattern being considered feminine or craftlike, you continued experimenting with this media in the United States. Why is that?

AQA: It became my mission to make people understand where I came from as many of my colleagues criticised the craft aspects of pattern and colour, motifs, floral arrangements, and calligraphy. I wanted to remain true to myself, and this inspired me to think about how I could enhance and promote the idea of women’s work being valuable. I disagreed with the misconception that if an object is too beautiful, it must be a craft and thus irrelevant. After graduation, I had more freedom and decided to continue exploring textile-inspired processes by elevating pattern to its highest level.

NR: Was pursuing your artistic approach with pattern difficult in the United States?

AQA: I arrived in the United States in November 1999 and was rather invisible then. But after 9/11, I suddenly became visible and realised how alien I was. I was further reminded of my earlier discomfort in Pakistan as a woman. To navigate the public spaces in Lahore, I had created an androgynous self; I had worn my hair very short to avoid being harassed and found safety in my androgyny. Starting out as a professional artist from 2000 onwards in the United States, I made it my mission to conceptually educate people regarding my identity through the use of pattern and surface embellishment, illumination, and shadows within my artwork, an identity which was not associated with the popular perceived terrorism.

Anila Quayyum Agha, Captive Shadow 1, 2020, mixed media on paper, charcoal, encaustic wax, embroidery, paper cutout, 30 x 30 in / 76.2 x 76.2 cm © Courtesy Anila Quayyum Agha

Anila Quayyum Agha, Sound of Silence 1, 2020, mixed media on paper, paper cutout, beads, embroidery, mylar, 25 x 29.5 in / 63.5 x 74.93 cm © Courtesy Anila Quayyum Agha

NR: Does your work express this androgynous identity?

AQA: My work has duality, permeating both the feminine and the masculine. I find contradictions interesting and strive to highlight them in my art practice. As an adolescent, I found safety in being androgynous to escape harassment as a female. Now, as an adult woman living in the United States, I am often the outsider, looking in, and consequently appreciate the ability to travel across boundaries. Using a variety of labour-intensive media to create large-scale sculptural installations which employ light and shadows, paintings, and embroidered drawings, I explore the deeply entwined political and social relationships between gender, culture, religion, labour, and climate change. I often use textile processes and sculptural methodologies to reveal and question the gendering of textile-derived work as well as the assumption that textiles are inherently a domestic craft and cannot be considered an art form. In my art practice, light and shadow act as metaphors for the contradictions which abound in the world, creating a dialogue regarding enlightenment, e.g., light travels far when there’s no obstruction while also creating shadows. This duality allows me to subvert both the feminine and the masculine by using scale and media which have historically been the domain of male artists.

NR: Do you consider yourself a feminist?

AQA: Yes, I’m a feminist. I believe everybody has value. In our world, value is often assigned to one’s body, based on gender, colour, origin, and location. Historically, brown and black bodies have been less valuable, and used for both paid and unpaid labour and commerce. I think people forget world history and, as an artist educator, I feel it’s my duty to educate not only through my artwork, but also by my feminist art practice to elevate value for women as well as non-binary and LGBTQ people. I guess in a way, I’m an artist for the minorities because I’ve been part of a minority for so long.

Anila Quayyum Agha, Intersections, 2022, lacquered steel and halogen bulb, 78 x 78 x 78 in / 198.12 x 198.12 x 198.12 cm, installation view, Mysterious Inner Worlds, The University of New Mexico Art Museum, Albuquerque, photo: Stefan Jennings Batista © Courtesy of University of New Mexico Art Museum and Anila Quayyum Agha

Anila Quayyum Agha, The Greys in Between, 2018, site-specific installation at MOCA Jacksonville, overall size of sculpture: 18 ft / 5.48 m, Walking With My Yesterdays (octahedron), laser-cut steel, lightbulb, powder coated, motorized movement, 10 x 5 ft / 3.04 x 1.52 m; Flowers Once Yours (tetrahedron) laser-cut steel, powder coated, lightbulb, motorized movement, 5 x 5 ft / 1,52 x 1,52 m, installation in a 35 x 20 ft / 10.66 x 6.09 m, space with the three inner walls painted a dark charcoal grey, photo: Doug Eng © Courtesy Anila Quayyum Agha

NR: What do decorative patterns represent for you? Do you draw inspiration from specific models of traditional ornamentation?

AQA: Patterns represent ways to create metaphorical structures and hierarchies in our contemporary societies. Often, I think of calligraphy, seeing the ebb and flow of the written words like reflections which filter through the trees. I like the interplay of density and openness within calligraphy and organic floral patterns. During my visits to the Alhambra Complex and to mosques and palaces in Pakistan, India, the United Arab Emirates, and Morocco, I realised how dense cultural patterns are – each of them are different and unique, but the whole creates an environment which is luscious, sensuous, and infinite. I think of the forgotten artisans, who spent hours making the stucco/plaster, carved wood, and the patterned marble with hard work and ingenuity. I identify with the unnamed artisans of yore, as I also felt undervalued in making work which was considered feminine or craft-like. Furthermore, I use an abundance of colour within my installation projects, to highlight the exoticising of the “cultural and gendered other”. In a sense, my complex patterns and bold colours allude to the expansive nature of the world when looked at through open feminist sightlines for its subversive inversion.

NR: Do you create all the designs for your installations?

AQA: Yes. I appropriate patterns from historical buildings, textiles, and art, melding them with additional elements and my own aesthetic sensibilities. In my work, one may find fragments or borders but not the complete patterns from past art, textiles, or architecture. Within my work, I combine the use of a layered and fragmentation approach. The process of putting elements together, searching for balance, is important. I work with my husband Steve Prachyl (b. 1961), who fabricates these big sculptures. During the drawing process, I get his feedback, informed by his Euro-Western background, on my designs. Our conversations follow the same ebb and flow of the contradictions between East and West. I like the flow, the density, the excitement of having abundance, and he likes openness and space, which results in a combination of both sensibilities, conceptually representing both East and West.

Anila Quayyum Agha, This is NOT a Refuge! 2, 2019, laser-cut, resin coated aluminum, light bulb, 93 x 58 x 72 in / 236.22 x 147.32 x 182.88 cm, exhibition view, Let a Million Flowers Bloom, The Columbia Museum of Art, Columbia, 2022 © Courtesy Anila Quayyum Agha

Anila Quayyum Agha, Refuge 1, 2019, mixed media on paper, laser-cut and mylar, 22.25 x 19 in / 56.51 x 48.26 cm © Courtesy Anila Quayyum Agha

Anila Quayyum Agha, Stealing Beauty (Steel Garden–After Durer’s A Great Piece of Turf), 2022, mirrored stainless steel, 57 x 151 in / 144.78 x 383.54 cm, installation view, A Moment to Consider, Sundaram Tagore Gallery, New York, 2022, photo: Sundaram Tagore Gallery © Courtesy Anila Quayyum Agha

NR: In your view, can pattern be political?

AQA: Yes, I think pattern is political, especially in view of the historical cultural appropriation visible in Western art, although in my work it is not overt but expansive and inclusive. I want to draw people into my artwork gently to stimulate dialogue.

NR: Is this why your works have this immersive quality?

AQA: I try to create an environment in which all people, irrespective of race, colour, creed, or gender, feel welcome and can experience a space where they can be simultaneously mysterious yet intimate with strangers. Giving visibility to the complexity of a diverse world with agency and value may help create a global intersectional policy.

NR: In This is Not a Refuge (installation, 2018), you address the issue of migration. Is this a recurring topic in your work?

AQA: Over the past decade, I have realised that human rights, women’s rights, and environmental politics are intimately connected. The erosion in our environment is immense, with diminishing resources, which in turn fundamentally impacts women worldwide. I think of women on the ground dealing with issues which affect their bodies, their children, their homes, and their income. The personal is political, and my personal politics have over time become the outer skin of my art practice. I think the politics of gender and climate change are intimately intertwined. The very same people and regions which were colonised for centuries are now being affected by climate change. As an artist, a woman of colour, and a person who was voluntarily displaced, I am very concerned about migration and climate change. Collectively, we need to deal with refugees, displaced people, resources, and borders in the present and into the future. The idea of finding refuge in our current global politics feels like a mirage.

NR: Could you tell us more about the idea of the “mirage” in This is Not a Refuge?

AQA: This piece was a response to how the United States used to be a beacon of light and can be again; a place where one could find freedom and achieve upward mobility, both of which I myself found. But in recent times, witnessing displaced people who are coming to our borders and being rejected made me realise that finding refuge can be a mirage for many. I think art can give visibility to subjects such as the politics of migration and displacement, to incite dialogue.

NR: How do you envision the relationship between East and West today?

AQA: To communicate on a deeper level, one must first create equity, harmony, and an exchange of knowledge between East and West. That’s partly why I create these inclusive environments; they draw people in, but also indicate that diverse cultures can bring value to one another. The world is not an island, but humans are adept at producing categorisations which generate divisive politics. Being a humanitarian and an educator, I create healing spaces where people can communicate and hopefully rise above and beyond their differences.

A shorter version of this interview was first published in the exhibition catalogue Re-Orientations: Europe and Islamic Art, from 1851 to Today (Kunsthaus Zurich, 24 March – 16 July 2023). Zurich: Hirmer; Kunsthaus, 2023, p. 18-19.

Anila Quayyum Agha (b. 1965) is internationally recognised for her award-winning large-scale installations which use light, shadow, and pattern to create inclusive, immersive, and shared experiences. Her international exhibitions include the Amon Carter Museum, Texas; the National Sculpture Museum, Valladolid, Spain; and the Chimei Museum, Taiwan. A. Q. Agha’s works have also been shown at international art fairs including Masterpiece London, India Art Fair (Delhi), Abu Dhabi Art Fair, and the Armory. Major awards she has received include the 2019 Painters and Sculptors Grant from the Joan Mitchell Foundation and the 2021 Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship. In 2019, A. Q. Agha’s work was included in She Persists at the Venice Biennale.

Nadia Radwan is an art historian and Privatdozent at the University of Bern and is currently teaching at the University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland. Her research focuses on transnational histories of avant-garde (surrealism, abstraction), modern, and contemporary art from the Middle East, gender in twentieth-century art movements, primitivism, and decolonisation in museum histories. She has contributed to several exhibition catalogues, notably for the Kunsthaus Zürich, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, the Palais de Rumine in Lausanne, and the Sharjah Art Museum. She is currently working on her second book, Concealed Visibilities: Sensing the Aesthetics of Resistance in Global Modernism.

An article produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring.

Nadia Radwan, "Interview with Anila Quayyum Agha: Pattern is Political." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/entretien-avec-anila-quayyum-agha-lornement-est-politique/. Accessed 2 July 2025