Research

Exhibition catalogue for Floating Images of Women in Art History from the Birth of Feminism toward the Dissolution of Gender (Yureru onna/yuragu imēji: Feminizumu no tanjō kara genzai made), Tochigi Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts, 1997; cover image: Emiko Kasahara, PINK #9 (detail), 1996, Chiba chrome print (5th edition), 127 x 157.5 cm. Collection of the artist

The Introduction of Gender Theory in the 1990s

How have Western feminist and gender theories that emerged in the 1970s been received and put into practice in Japanese art history, criticism, and exhibitions? Linda Nochlin’s essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”1 was translated comparatively quickly in 1976, and Midori Wakakuwa was one of the earliest art historians to implement feminist and gender theory. She has since deepened her research output through gender theory and the discovery of women artists, compiling her findings into a series of published volumes.2

In this work, M. Wakakuwa was not alone. The Eastern Division of the Japan Art History Society (Bijutsushi Gakkai) held two conferences on feminist art history (in 1992 and 1993, respectively); a report of the second meeting was published in Bijutsushi along with selected papers.3 This became the impetus for launching the Image & Gender Conference (Imejī & Jendā Kenkyūkai) in 1995, which has resulted in research presentations being given at regular meetings several times a year. A research bulletin, Image & Gender, was published roughly every year, with publication beginning in 1999 and ceasing in 2010 after ten issues.4 Furthermore, a collection of essays, Bijutsu to jendā: Hitaishō no shisen (Art and Gender: An Asymmetrical Gaze) was published in 1997, while feminism and gender-theory studies have produced significant results in both Western and Japanese art history ever since.5

Responding to this art-historical movement, art museums that had opened across Japan’s prefectures and in its major cities in the 1980s held numerous exhibitions with a gendered perspective in the late 1990s. These were mainly organized by women curators. Among these was my own exhibition, Floating Images of Women in Art History from the Birth of Feminism to the Dissolution of Gender (Yureru onna/yuragu imēji: Feminizumu no tanjō kara genzai made, 1997).

Issue 3 of the art and exhibitions criticism magazine, LR (August 1997), in which Haruo Sanda’s “Thoughts on the State of the Field 3: Concerning Borrowed Ideas, Wisdom, and Themes” (Jōkyōkō 3: Karimono no shisō, chi, shudai o megutte) was published, this was the first critique of a gender-based exhibition

The Gender Controversy, 1997–1998

However, these new horizons in art history and the museum faced criticism of gender theory, coming both from the academy and the world of journalism. In response, those involved, myself included, offered rebuttals, and this exchange led to a series of debates—later known as the “Gender Controversy”—that were carried out from 1997 to 1998 in the arena of small-readership journals.6 In recent years, the “Gender Controversy” has drawn attention from younger generations who were not aware of it at the time. In 2021, the Image & Gender Conference held a symposium during which responses from generations new and old were heard. Following that, primary source materials from the period were made available to the public.7 In simple terms, critics shared a common opposition to the incorporation of “Western ideology” like gender theory into Japanese art history and exhibitions as well as an aversion to bringing social issues, such as “accusations of sexism,” into “art.” In the words of Kaori Chino, one of the participants in the debate, “The biggest issue underlying this gender controversy is whether or not a separate world of ‘art’ exists independently of the real world.”8 Art cannot exist apart from society and politics. When one considers contemporary art criticism, where the trend of socially engaged art is also becoming increasingly widespread, these critics’ perceptions seem even more narrow-minded, but they have yet to be completely eradicated from academia or art-exhibition audiences.

Exhibition catalogue for gender—beyond memory: The Works of Contemporary Women Artists (jendā—kioku no fuchi kara), Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, 1996, curated by Michiko Kasahara

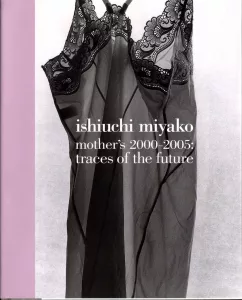

Miyako Ishiuchi’s Mother’s 2000–2005: Traces of the Future (Mazāzu 2000–2005: Mirai no kokuin) (Tokyo: Tankosha, 2005), a photo book published in conjunction with the exhibition held at the Japan Pavilion during the 51st Venice Biennale

Bashing and Backlash Against “Gender Free” since the 2000s

Increasingly thereafter, between 2002 and 2006, “gender-free bashing” spread throughout the country, having developed into a social problem due to national regulations, and this had a tremendous influence on wider Japanese society.9 As many have noted, although women’s circumstances have not really improved, the term “gender” itself has been squandered, losing its evocative power.10 Nevertheless, art-historical research based in gender theory has been published steadily in dissertations since the 2000s and, more recently, in popular books on the subject.11

In 2001 and 2005, respectively, I organized two exhibitions of women artists at the Tochigi Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts, using as a basis my survey of modern Japanese women artists from the 1930s onward and the social systems surrounding women of that period.12 Moreover, broadening the view to include all of Asia, four museums—beginning with the Fukuoka Museum of Asian Art—collaborated to open Women In-Between: Asian Women Artists (Ajia o tsunagu: Kyōkai o ikiru onna-tachi), which was held from 2012 to 2013.13 Meanwhile, pioneering the curation of exhibitions on gender since 1991, Michiko Kasahara has held numerous gender-focused shows at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum from the 1990s into the 21st century.14 Additionally, M. Kasahara selected photographer Miyako Ishiuchi for the 51st Venice Biennale in 2005, bringing the artist to international acclaim.15 Consequently, younger women curators have held exhibitions reevaluating women artists at museums in every region of the country, with these initiatives seeing particular success from 2020 to 2022.16

Exhibition catalogue for Women In-Between: Asian Women Artists, 1984–2012 (Ajia o tsunagu: Kyōkai o ikiru onna-tachi, 1984–2012), Fukuoka Asian Art Museum et al., 2012; cover image: Suknam Yun, Pink Room 5, 1995–2012; installation; sofa, Korean rice paper, beads, glass, and other materials. Collection of the artist

And Today

Now, in 2025, exhibitions that sharply display gender consciousness are held not just in art museums but also such venues as galleries.17 Many of the curators and artists who organize these exhibitions are from a younger generation, born in the late 1980s and 1990s, who have not been directly impacted by the aforementioned “gender backlash,” and there is much hope for this promising future generation.

Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” Artnews 69, no. 9 (January 1971): 22–39, 67–71; reprinted in Art and Sexual Politics: Women’s Liberation, Women Artists, and Art History, ed. Thomas B. Hess and Elizabeth C. Baker (New York: Macmillan, 1973), 1–39. This was published in Japanese by Kazuko Matsuoka (trans.), “Naze josei no dai geijutsuka wa arawarenai no ka?” Bijutsu Techō 5 (1976): 46–83.

2

Midori Wakakuwa, Josei gaka retsuden [Biographies of Women Artists] (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1985) and Shōchō to shite no joseizō: Jendā-shi kara mita kafuchōsei shakai ni okeru josei hyōshō [Images of Women as Symbols: Viewing Representations of Women in Patriarchal Society through Gender History] (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, 2000), among others. See also Reiko Kokatsu, “Bijutsushi to jendā: Nihon no bijutsushi kenkyū, bijutsuten ni okeru jendā shiten no dōnyū to genjō” [Art History and Gender: An Introduction and Overview of the Gender Perspective in Japanese Art Historical Research and Art Exhibitions], Jendā shigaku 12 (2016): 75 –79, whose bibliography is also available online at https://asianw-art.com/bibliography/.

3

Bijutsushi 136, vol. 43, no. 2, 235-257(March 1994).

4

Back issues of the magazine Image & Gendermay be downloaded from the Women’s Action Network website: https://wan.or.jp/dwan/detail/6179.

5

Bijutsu to jendā: Hitaishō no shisen [Art and Gender: An Asymmetrical Gaze] (Tokyo: Brücke(Burrukke), 1997). See also the references in Kokatsu, “Bijutsushi to jendā,” available online at https://asianw-art.com/bibliography/.

6

For the particulars of this series of debates, see Megumi Kitahara, “Nihon no bijutsukai ni okeru ‘taka ga seibetsu’ o meguru ronsō, 1997–98” [Debates Concerning “Mere Sexual Difference” in the Japanese Art World, 1997–98] Impaction 110 (October 15, 1998): 96–107; and Kaori Chino, “Bijutsukan, bijutsushigaku no ryōiki ni miru jendā ronsō, 1997–98” [Gender Debates in the Arena of Art Museums and Art Historical Study, 1997–98], in Onna? Nihon? Bi?: Arata na jendā hihyō ni mukete, ed. Kaori Chino and Takaaki Kumakura (Tokyo: Keiō Gijuku Daigaku Shuppankai, 1999), 117–54. An English translation of Kitahara’s paper by Ayako Kano is available on Art Platform Japan: https://artplatform.go.jp/readings/R202108.

7

“Ima, jendā ronsō o furikaeru” [Looking Back on the Gender Controversy], Image & Gender Conference, Zoom Symposium, July 18, 2021. Following the symposium, primary source materials on the “Gender Controversy” were made available online at https://imgandgen.org/gender-controversy-material/.

8

Chino, “Bijutsukan, bijutsushigaku no ryōiki ni miru jendā ronsō,” 142.

9

Midori Wakakuwa, Shūichi Katō, Masumi Minagawa, and Chieko Akaishi (eds.), “Jendā” no kiki o koeru!: tettei tōron! Bakkurasshu[Overcoming the “Gender” Crisis! Complete Debate! Backlash] (Tokyo: Seikyūsha, 2006). See also the following publications that were produced by exchange students who participated in this symposium: Sŏk Hyang, Jendā bakkurashu to wa nandatta no ka: Shiteki sōkatsu to mirai he mukete [What Was the Gender Backlash? Historical Overview and Looking to the Future] (Tokyo: Inpakuto Shuppankai, 2016); and Yumi Ishikawa (ed.), “Tokushū: Josei undo to bakkurasshu” [Special Feature: The Women’s Movement and Backlash,” Femi MagajinETOSETORA(etc) 4 (February 2020).

10

Akiko Kasuya, “Josei sakka-tachi no gendai: Bijutsu ni okeru jendā” [Contemporary Women Artists: Gender in Art], Bijutsu fōramu 21, 30 (2014): 115–20.

11

For more on these publications, see the references in Kokatsu, “Bijutsushi to jendā,” which are also available online at https://asianw-art.com/bibliography/.

12

Japanese Women Artists before and after WWII, 1930s–1950s (Tochigi Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts, 2001); Japanese Women Artists in Avant-Garde Movements, 1950–1975 (Tochigi Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts, 2005). For more on these, see Reiko Kokatsu, “Postwar ‘Avant-Garde’ Art Movements and Women Artists, 1950s–60s,” trans. Nina Horisaki-Christens, Art Platform Japan:https://artplatform.go.jp/readings/R202003, which is an English translation of an essay first published in the catalogue for the latter exhibition.

13

Women In-Between: Asian Women Artists, 1984–2012 (Fukuoka Asian Art Museum, Okinawa Prefectural Museum & Art Museum, Tochigi Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts, Mie Prefectural Art Museum, 2012–2013). Essays from the exhibition catalogue are available online at: https://asianw-art.com/project/.

14

For exhibitions organized by Michiko Kasahara, see the references in Kokatsu, “Bijutsushi to jendā,” which are also available online at https://asianw-art.com/bibliography/. Since 2017, M. Kasahara has organized the exhibitions Dayanita Singh, Museum Bhavan, in 2017, and I Know Something About Love: Asian Contemporary Photography, in 2018 (both at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum).

15

See the exhibition page at https://venezia-biennale-japan.jpf.go.jp/j/art/2005.

16

See “Tokushū: Josei-tachi no bijutsushi” [Special Issue: Women’s Art History], Bijutsu Techō 73, no. 1089 (August 2021).

17

Reiko Kokatsu, “Āto to jendā no genzaichi” [The Current State of Art and Gender], Gekkan Āto Korekutāzu Monthly Art Collecters197 (August 2025): 106–7.

Reiko Kokatsu is an art historian and critic, formerly chief curator at the Tochigi Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts. Her specialties are modern and contemporary art and gender studies. She lectures at Jissen Women’s University and Kyoto University of the Arts. She was in charge of a number of exhibitions that discovered and re-evaluated modern and contemporary women artists in Japan and other parts of Asia, including Floating Images of Women in Art History (1997), Japanese Women Artists before and after World War II, 1930s–1950s (2001), Japanese Women Artists in Avant-Garde Movements, 1950–1975 (2005), and Women In-Between: Asian Women Artists, 1984–2012 (2012–13), all held at the Tochigi Prefectural Museum of Fine Arts. She also curated Women’s Lives: Disease, Aging, Death, and Rebirth at the Saitama Triennale in 2023.

She has co-authored, with Mayumi Kagawa, the book Kioku no Amime wo Taguru, Art to Gender wo Meguru Taiwa [Tracing the Web of Memory: A Ⅾialogue on Art and Gender] (Tokyo: Saiki-sha, 2007) and, with Megumi Kitahara et al., the volume Asia no Josei shintai ha Ikani Egakaretaka, Shikaku Hyōshō to Sensō no Kioku [How Were Asian Women’s Bodies Depicted?: Visual Representations and Memories of War] (Tokyo: Seikyū-sha, 2013). Since 2020, she manages the website Asian Women Artists: Gender/History/Border (https://asianw-art.com).

Reiko Kokatsu, "On the Introduction of Gender Perspectives into Japanese Art History and Exhibitions." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/introduction-dune-approche-de-genre-dans-lhistoire-de-lart-et-dans-les-expositions-artistiques-au-japon/. Accessed 24 February 2026