Interviews

For more than forty years, Ishiuchi Miyako has been questioning history and revealing hidden stories with her photographs. This interview, which was conducted at her home in Kiryū, Japan, in December 2019, shows how women have found themselves at the centre of efforts for greater visibility: witnesses, key actors, anonymous models and artists are given pride of place in the closely framed pictures of the most famous Japanese photographer of her generation.

Anaïs Roesch: Ishiuchi Miyako, you were born in 1947 and spent most of your childhood in Yokosuka, home to a major military port. How did the post-war context influence your work?

Ishiuchi Miyako: My encounter with the city was highly influential to me. I was born in the Gunma prefecture, but my mother, younger brother and I joined my father in Yokosuka, where he was working, when I was old enough to go to school. I lived there from ages six to nineteen. There was an American navy base there and, to my great surprise, I discovered the existence of a frontier. I was forbidden to use certain streets because rapes had happened there – that’s how I found out I was a woman. In this occupied town, sex crimes were a common occurrence. Locals had become used to them as if they were normal, but I, as an outsider, could not accept it. I was shocked. The rapes committed by American troops in Okinawa during the battle of 1945 and later by Allied forces were only reported in 1995, but they still have not been prosecuted in Yokosuka.

My feelings about the town were complex when I was a child: it disgusted me, and yet at the same time I felt attracted to it.

Matylda Taszycka: You devoted your first photographic series to it.

IM: Yokosuka Story (1977-1978) was the starting point of my whole career. To me it was like returning to my roots. I wanted to express my pain. In my first series, such as Apartment (1978-1979) and Endless Night (1978-1980), I tried to turn my wounds into pictures.

AR: Other artists showed an interest in Yokosuka before you did. Were you aware of their work? How was your approach different from theirs?

IM: I started photographing Yokosuka because I felt I was the only one who could reveal the city’s true face. Of course, I was aware of the series made by Daidō Moriyama (born in 1938) and Shōmei Tōmatsu (1930-2012). However, they took pictures of the American quarter, which made sense to them in the context of the protests against the Vietnam War. D. Moriyama and S. Tōmatsu pictured Yokosuka through the eyes of men, whereas I, as a woman, was not allowed access to the American base. They photographed America, whereas I depicted the story of my childhood. My approach was more intimate. I mapped out all of the neighbourhoods surrounding the military base and made three series in total.

MT: Time is an overarching theme in your entire body of work. In 1.9.4.7. (1988-1989), for instance, you closely examine the bodies of women born the same year as you. Why is that?

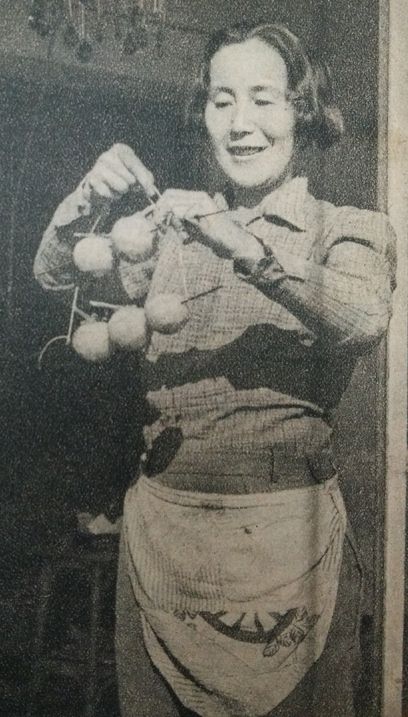

Ishiuchi Miyako, 1.9.4.7 #49, 1988-1989, © Ishiuchi Miyako

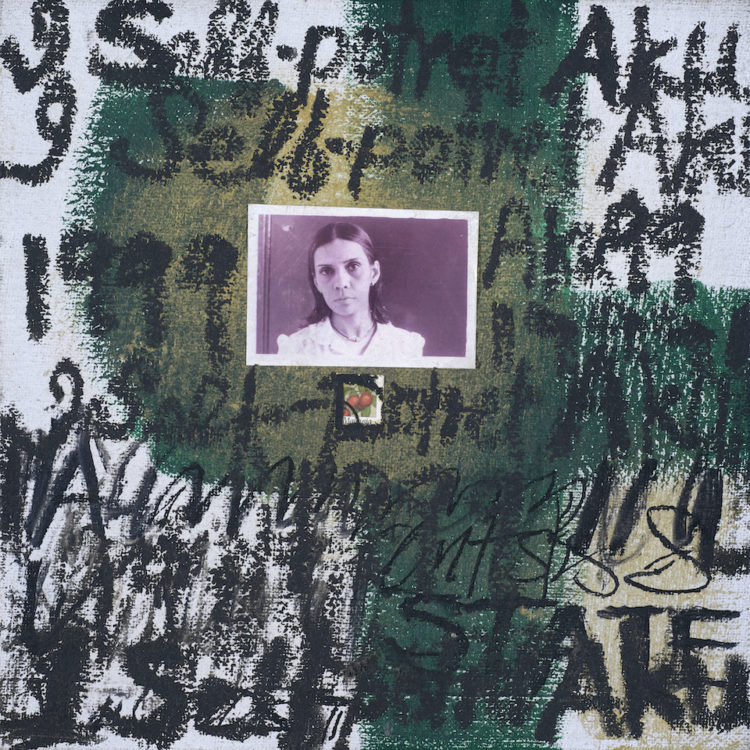

Ishiuchi Miyako, Scars #13, 1996, © Ishiuchi Miyako

IM: I had just turned forty when I started working on that series. I wondered how I could make the passing of time visible. How does one photograph the forty years of a lifetime? I decided to try and capture these traces as seen on the hands and feet of fifty women. All of them bore the marks of the passing of time and of the various occupations they had. I found them beautiful. It was a self-portrait of sorts, in that I identified with my models.

I then took an interest in scars. Like the previous series, Scars (1991-2017) stems from my personal history. We each have our own pains and wounds, which in my opinion are proof that we are still alive.

Later on, for the Apartment series, I photographed the decrepit walls of buildings. To me, walls are the skin of buildings and bodies are part of the architecture. There is continuity within these three series:1 they all came from a will to capture time and turn it into images.

Ever since I started photographing, I have enjoyed working in the darkroom, and I still do. It’s what has defined me as an artist. The final prints are less important to me than the creative process itself. Developing in the darkroom reflects my relationship to time. Much like the series Scars or ひろしま/hiroshima (2007-ongoing), in which I took pictures of objects that belonged to victims of the atomic bomb, the goal is to freeze a point in time.

Photography enables one to capture something that cannot be seen with the naked eye. It weaves a link between the past and the present, and is therefore an invaluable testimony and a tool for transmission. I have recently discovered the importance of the image as a trace. All of her life, my mother kept a group portrait in which she can be seen with fellow graduates from her driving school in 1934.

AR: You devoted the very personal series Mother’s (2000-2005) to her. Much like a portrait in negative, you meticulously documented her personal belongings: underwear, shoes, lipstick, and so on.

IM: My mother passed her driving licence at the age of eighteen; she was the second woman to drive in the Gunma prefecture and the first who came from a working-class background. From that age, she became a lorry driver at the American army base. I photographed her when I was working on Scars because she had a burn mark. She died unexpectedly ten months later. I didn’t know she was going to die when I was documenting her scars. It came as an absolute shock to me. That was when I began to immortalise her belongings. It felt like a way of prolonging my discussion with her.

The series was shown in the Japanese Pavilion at the 51st Venice Biennale in 2005. It marked a turning point in my career, which then took off at a more international level. Mother’s was later presented at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum (TOP Museum), curated by Michiko Kasahara. Following this exhibition, I was asked to create a similar work with the objects kept at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

In a way, I owe this whole evolution to my mother.

MT: You studied textile design at Tama Art University in Tokyo. What led you to begin working with the photographic medium?

IM: I studied weaving at university. I only picked up my first camera when I was twenty-eight. An acquaintance of mine had provided me with the necessary tools to work in a darkroom. I decided to use them because I had time on my hands. I bought rolls of film rolls, paper and chemicals. When I first set foot in a darkroom, I felt overwhelmed by a sense of nostalgia. The products required were the same as those used to fix colour on fabric. I understood that photography was like dyeing. One often thinks that fabric is flat, while it is in fact in relief. Light and air pass through it, as they do with film or the grain of a silver print. This is why my vintage prints were so large. When I made my first pictures, I used a 20-metre roll of paper, as if I were working on dyeing fabric. I rediscovered them recently while I was moving.

Fabric is what is closest to the body, which it protects and enhances. Underwear, for instance, is like a second skin. In ひろしま/hiroshima, as in Mother’s, I took an interest in the clothes that are left behind when someone dies. The imprint that a body leaves on fabric is full of meaning to me, in that it is the proof of the person’s existence.

AR: You took part in the student uprisings that happened in universities in 1968. How did that period affect your later commitments, especially in your work with women?

IM: In 1968 the men were on the barricades while the women were kept in the kitchens. Uprisings were always led by men, and this traditional allocation of roles didn’t sit well with me. So I quickly gave up on that commitment. On the other hand, I was engaged in the women’s liberation movement from its very beginning.2 In 1976 I organised the exhibition Hyakka Ryōran [A hundred flowers bloom] at the Shimizu Gallery in Yokohama, which showed the works of ten women photographers, including myself. I was twenty-nine at the time and felt I hadn’t been involved enough in the fight for equality. The project was born out of this regret. The other artists invited were also in their twenties. Half of them later put an end to their career, and others have since died. Women faced heavy discrimination in the field of photography at the time. We organised on our own and deliberately reversed traditional roles by choosing to take portraits of men. We reappropriated the subject for ourselves. I, for instance, chose to photograph male nudes. I also wrote the presentation text for the exhibition, which I intended as a kind of manifesto. It was also a truly collaborative project, so we decided to not sign our works. Despite our efforts, the art world ignored us entirely. It amazes me that the exhibition is viewed as increasingly important nowadays. In 1976 it only caught the attention of the television and tabloids, which were attracted to the provocative nature of its content! It marked the beginning of my career. One year later, I made Yokosuka Story.

The remorse I feel of not having been sufficiently involved in the student uprisings is still very present in me. I am looking for a kind of relationship with society through my work as an artist.

MT: Would you call yourself a feminist?

IM: I am interested in women because I am a woman myself. I assert my identity, but I was never an activist. To me the exhibition Hyakka Ryōran was the stance I needed to take in order to become an artist.

From a historical point of view, discrimination is a fact that continues to exist to this day. Artistic expression can be used as a tool to denounce what we disapprove of. It’s what I do with my pictures: I reveal the issues that matter to me. When I photographed the old brothel in Yokosuka in Endless Night, my aim was to criticise the commodification of women’s bodies. It was a way for me to show commitment in regards to other women.

Asserting myself as a woman has always felt natural to me, but I don’t feel the need to take a political stance about it. The curator of the exhibition, M. Kasahara, on the other hand, is a true feminist!

AR: In 2012, you were commissioned by the Casa Azul (now Museo Frida Kahlo) in Mexico City to document over three hundred items that had belonged to the artist. What does this commission say about your interest in Frida Kahlo (1907-1954)?

IM: The series Frida by Ishiuchi came after Mother’s. After seeing my work documenting my mother’s personal belongings, Circe Henestrosa, the curator of the exhibition Appearances Can Be Deceiving: The Dresses of Frida Kahlo (2012-2013, Museo Frida Kahlo, Mexico City), contacted me to immortalise the artist’s clothes, which were discovered in 2004 when a bathroom that Diego Rivera (1886-1957) had sealed shut was reopened. Before I accepted the invitation, I had only seen F. Kahlo’s paintings as reproductions and didn’t particularly like them. Once I arrived on site, I was blown away. My vision of her and of her work changed. I had imagined a strong woman with a life filled with love affairs. This wasn’t what I discovered when I saw her work. F. Kahlo was first and foremost a serious artist in search of her identity. Her relationships with men served her art. I finally got to understand her.

This encounter encouraged me. It was a wonderful experience, and I will forever be thankful to my mother for having provided the opportunity for this project through the series Mother’s.

MT: Have you been inspired by other women artists? What do you think of the younger generation for which you have in turn become a reference?

IM: The first Japanese female photographer, Shima Ryū (1823-1900), came from Kiryū,3 like I do. I left when I was six, but I have now moved back. I am self-taught, so I can’t say that I was inspired or influenced by earlier generations. When I was younger, I was interested in the work of Cindy Sherman (born in 1954) and, as of late, I have rediscovered the works of Eiko Yamazawa (1899-1995).

It was hard to find ten women photographers for my exhibition in 1976. The situation has changed a great deal since. In those days, many artists gave up their practice after they married. Nowadays, they can choose to keep going because men are changing too. There are a lot of talented female artists – as a matter of fact, all the best pictures these days are always taken by women. The growth of digital photography, which has enabled us to break the boundary between the artistic and the commercial approach, has also helped increase the number of women photographers.

The situation remains complicated on the whole, but photography is a medium that suits women well, and more and more of us are willing to assert ourselves as photographic artists!

Yokosuka Story, Apartment and 1.9.4.7.

2

The late 1960s witnessed the beginning of the Japanese women’s liberation movement, called Ūman Ribu (from the English “women’s liberation”). This second feminist wave brought together various women’s groups and organisations all around the country. The creation of the movement coincided with the appearance of radical feminist movements in the United States and other countries.

3

Shima Ryū is a pioneer in the history of photography in Japan. She studied at an art school in Edo (today’s Tokyo), where she met her future husband, Shima Kakoku (1827-1870). In 1855 the couple settled in the Kantō district, where they both learnt the basics of the new medium. During the spring of 1864, Shima Ryū photographed her husband, making her the first female photographer in Japan. The couple ran a studio from 1865 to 1867 at which date Shima Kakoku was offered a teaching position at the Kaiseijo Institute for Western Studies. After her husband’s death, Shima Ryū returned to her hometown, where she opened her own studio.

Miyako Ishiuchi, Anaïs Roesch & Matylda Taszycka, "Ishiuchi Miyako: Photography as a Trace." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/ishiuchi-miyako-la-photographie-comme-trace/. Accessed 3 July 2025