Research

Brochures, application forms, 1975-80, Women’s School of Planning and Architecture records, Sophia Smith Collection, SSC-MS-00306, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts, Smith College Special Collections

“The private is political” was a common rallying cry amongst second-wave feminists in the 1960s and 1970s. As well as pedagogy, it seems. In the United States, the early 1970s saw many initiatives aimed at exploring novel ways of pedagogy, in particular by condemning power dynamics.

In 1971, artist and graphic designer Sheila Levrant de Bretteville (1940) developed visual branding for the California Institute of the Arts, a school renowned for its experimental spirit, promotion of interdisciplinary approaches and emphasis on fostering critical thinking. She taught there alongside fellow artists Miriam Schapiro (1923–2015) and Judy Chicago (1939–), who together founded the Feminist Art Program in the same year. S. L. de Bretteville set up the first Women’s Design Program, which offered consciousness-raising sessions, performance workshops and feminist book-discussion groups. The Womanhouse and Feminist Studio Workshop projects crystallised the goals of these events. In 1972 a partnership between the Center for Independent Living (CIL), composed of a dozen students with major disabilities, and the College for Environmental Design at the University of California Berkeley challenged the notion of accessibility, notably with the participation of the architect Raymond Lifchez (1932–2023). Design work took place in collaboration with students living with disabilities: the classroom itself became a space that informed the design of spatial transformations and assistance networks needed for everyone to be able to work together.

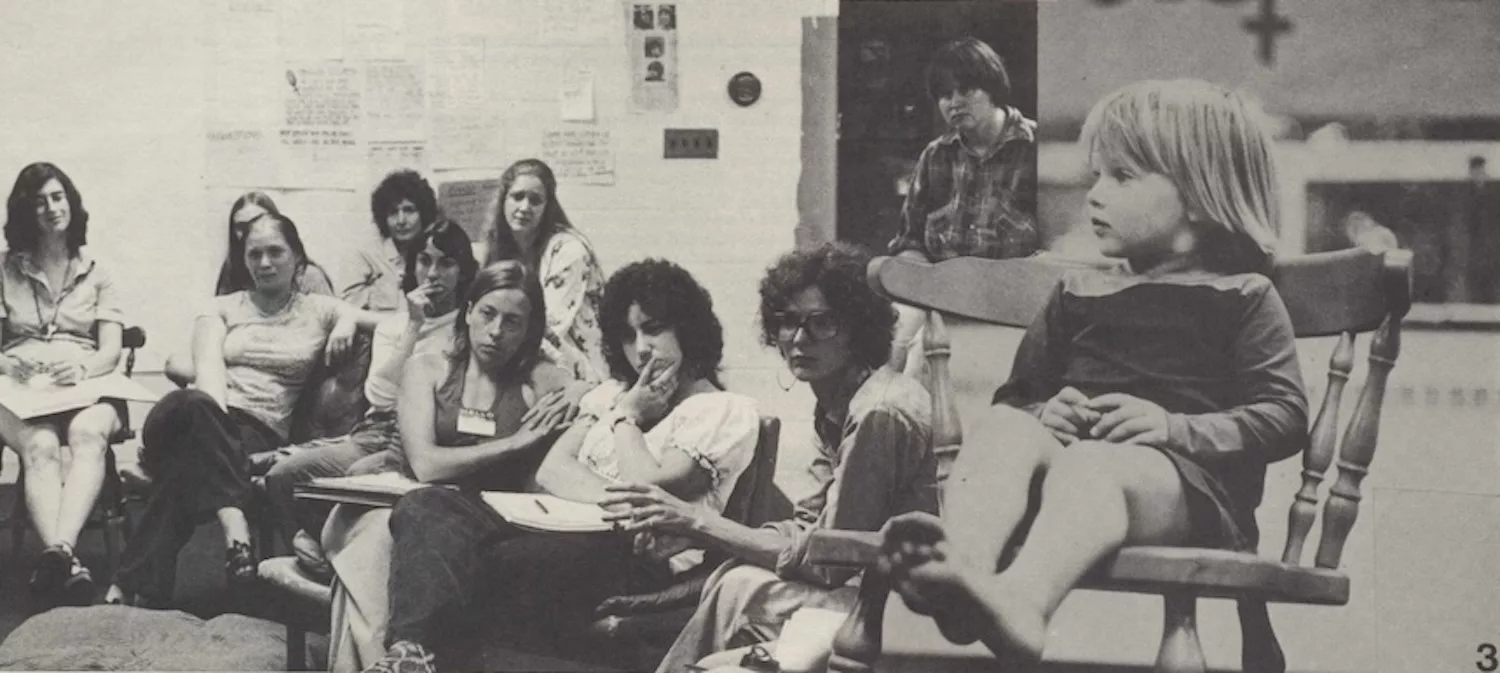

Phyllis Birkby and Leslie Kanes Weisman included the fantasy environment exercise in their core course, “Women and the Built Environment: Personal, Social, and Professional Perceptions,” at the first session of the Women’s School of Planning and Architecture in Biddeford, Maine, August 1975, Women’s School of Planning and Architecture Records, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Mass, Smith College Special Collections

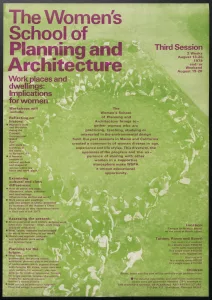

In the United States, discrimination against women in federally funded education programmes was not prohibited until 1972, the year in which Title IX was enacted. At the time, the American Institute of Architects listed only 528 women architects (of the total 42,043), or 1.25% of the profession.1 In 1974, in a continuation of several experimentations involving radical pedagogy,2 seven women set up an experimental summer programme, the Women’s School of Planning and Architecture (WSPA), which offered sessions between 1975 and 1979. They would meet at feminist events such as those of the Alliance of Women in Architecture in New York and the Women in Architecture symposium. Each revolved around women’s role and standing within the architecture profession.

Katrin Adam (birthdate unknown), Ellen Perry Berkeley (1931–2024), Phyllis Birkby (1932–1994), Bobby Sue Hood (1932–1994), Marie Kennedy (1918–2005), Joan Forrester Sprague (birthdate unknown) and Leslie Kanes Weisman (1945–) came from different walks of life and did not always hold the same opinions on feminism. But they all shared the belief in spatial politics, that is spatial organisation is a component of the opppression of women. Their common aim, with architecture training, was to challenge notions and portrayals of the architect-author and promote a collective depiction. They criticised the hierarchies at architecture schools, proposing that pedagogy be viewed as a dialogue rather than a unidirectional, top-down imparting of knowledge. Between 1975 and 1979, the WSPA organised four two-week August sessions, each attracting around sixty women. In 1981, a symposium drew over two hundred attendees.

Poster for the WSPA’s Third Session featured an iconic image taken during the First Session in 1975: the participants posed themselves as a giant women’s symbol, 1978, Susan Aitcheson Private Collection, Smith College Special Collections

This summer school was unique in its ability to unite women from all over the country – regardless of their educational background or qualification type – around a common fascination with the built environment. The sessions were organised in different cities to make participation accessible to as many women as possible. Each year, the brochure would clearly state the session’s operational details, including travel options, registration process, credit recognition and pricing. Women were encouraged to bring their children (aged three to twelve); as an on-site child-minding service was available, they could still participate fully in the session activities. Designed as an independent, affordable school, a ‘mobile community’, the WSPA functioned as an experimental venue in which a collective female identity could be developed within a male-dominated profession. Each summer, a new theme determined the content and continued into the following year through contributions from participants keen to engage in the upcoming educational programme.

WSPA Third Session Coordinators Susan Aitcheson, Joan Forrester Sprague, and Katrin Adam (subsequently founders of WDC), 1978, Susan Aitcheson Private Collection

Over the programme’s four‑year span, common themes included attention to local contexts, structural aspects, practices and uses and the architect’s role. Other more specific topics demonstrated an early interest in unconventional aspects of architectural design that would not be addressed in traditional academic curricula for another forty years. These included concerns related to the environment, the climate, rehabilitation and transformation, social housing and, more crucially, feminist perspectives. Teaching methods varied, ranging from full-scale construction projects and immersive study trips to exploratory walks and seminars. The core courses, taught by panels of instructors to prevent reliance on a sole authority figure, were held in small groups that would then expand into discussion sessions open to all participants.

From the start, the programme sought to create a nurturing environment conducive to the free exchange of ideas in a setting that would feel like a retreat. It aimed not only to encourage women to develop both personally and professionally by embracing their values and identities as women and designers but also to offer a forum in which participants could discover and define specific strengths, concerns and abilities that women contribute to society and the environmental-design professions. For the final session, in 1979, the organisers made no secret of their intention to influence the academic world through a feminist perspective and to bring about change in the curriculum. This intertwining of woman and designer, personal and professional, fuelled the school’s vision and pitched a question very much in line with the times: might there exist female-specific approaches to designing spaces, and if so, what would they be?<

Brochures, application forms, 1975-80, Women’s School of Planning and Architecture records, Sophia Smith Collection, SSC-MS-00306, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts, Smith College Special Collections

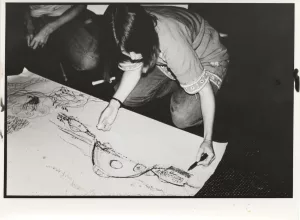

As an example, ‘Women’s Fantasy Environments’ was the title of one workshop run by P. Birkby, who had already introduced this practice in many other contexts. It employed awareness-raising approaches aimed at uncovering and challenging social models dictated by gender norms with a view to implementing measures designed to gather support for gender equality. Participants were given large rolls of paper and encouraged to sketch their ideal living spaces without regard for practical constraints of any kind. The aim was to elicit connections between these women’s personal desires and their insight, as professionals, into usages and spatial configurations best suited to women. In this way, dreams and desires could become vectors of social and personal change. As P. Birkby wrote, “All we had around us was originally fantasized by men since they were the ones, I too acutely felt, that dominated the very processes that controlled and led to [the] physical form[s] that shaped our very existence”.3 P. Birkby believed that fantasy alone could enable women to shake off their psychological conditioning and begin to imagine new spaces. But the true value of these practices seemed to lie in the role they played in raising awareness of gaps between the reality, projections and needs of society, especially where women were concerned.

The 1978 session focused on adapting this method to gear it toward social justice and women’s access to certain spaces. After this experience, three session participants turned their aspirations into reality by founding the Women’s Development Corporation, an organisation dedicated to designing, constructing and managing affordable, high-quality housing for low-income women, people with special needs and the aged.4

More than just a venue for learning, the Women’s School of Planning and Architecture served as a vital space for women to share ideas and gain the liberating knowledge they needed to challenge contemporary living conditions and architecture practices. By the dawn of the 1980s, the question raised by the WSPA had shifted from examining women and architecture to exploring ‘female’ principles in architecture practice.5 Instead of revisiting form-based architectural differentiations, many authors strove to define these female principles, emphasising nuanced variations rather than mutually exclusive categories or taking a radical position pitting a socially minded ‘feminine’ against a profit-seeking ‘masculine’. For instance, one female principle was a socially oriented (as opposed to profit-driven) design.

The American Institute of Architects, Status of Women in the Architectural Profession, Task Force Report, February 1975, https://content.aia.org/sites/default/files/2018-03/Archives_StatusWomenArchitecturalProfession_1975.pdf.

2

Beatriz Colomina et al., Radical Pedagogies, Cambridge, London: MIT Press, 2022.

3

Stephen Vider, “Fantasy is the beginning of creation”, Platform, June 2021 [date to be confirmed], https://www.platformspace.net/home/fantasy-is-the-beginning-of-creation.

4

Andrea J. Merrett, “The personal is professional”, in B. Colomina, Radical Pedagogies, op. cit., p. 269.

5

See Paola Coppola Pignatelli, “Der Weg zu einer anderen raumlichen Logik”, Bauwelt Frauen in der Architektur! Frauenarchitecktur?, no. 31–32, August 1979, pp. 1285–1288; Margrit I. Kennedy, “Toward a rediscovery of ‘feminine’ principles in architecture and planning”, Women’s Studies International Quarterly, vol. 4, no. 1, 1981, pp. 75–81, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-0685(81)96388-0; K. A. Franck, “A feminist approach to architecture”, in Ellen P. Berkeley and Matilda McQuaid (ed.), Architecture: A Place for Women, Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989, pp. 201–216.

6

Voir Paola Coppola Pignatelli, « Der Weg zu einer anderen raumlichen Logik », Bauwelt Frauen in der Architektur ! Frauenarchitecktur ?, nos 31-32, août 1979, p. 1285-1288 ; Margrit I. Kennedy, « Toward a rediscovery of ”feminine” principles in architecture and planning », Women’s Studies International Quarterly, vol. 4, no 1, 1981, p. 75-81, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-0685(81)96388-0 ; K. A. Franck, « A feminist approach to architecture », dans Ellen P. Berkeley et Matilda McQuaid (dir.), Architecture : A Place for Women, Washington, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989, p. 201-216.

Stéphanie Dadour is associate professor at Ensa Paris-Malaquais and co-founder of the Dadour de Pous Architecture office. Her teaching, research, and projects focus on expressions of power and asymmetrical relationships in archtiecture and planning practices. Among her publications are Des voix s’élèvent. Féminismes et Architecture, Enseigner l’architecture à Grenoble. Une histoire, des acteurs, une formation (with S. Le Vot), The Housing Project. Discourses, ideals, models and politics in 20th c. exhibitions (with G. Caramellino) and 1989, hors-champ de l’architecture officielle : Liban.

Stéphanie Dadour, "Pedagogy is political: the Women’s School of Planning and Architecture." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/la-pedagogie-est-politique-la-womens-school-of-planning-and-architecture/. Accessed 24 February 2026