Research

Patricia Piccinini, The Young Family, 2003, silicone, acrylic, human hair, leather, timber, 89 x 164 x 142 cm, Bendigo Art Gallery, Victoria, photo: Leon Schoots © Courtesy Patricia Piccinini

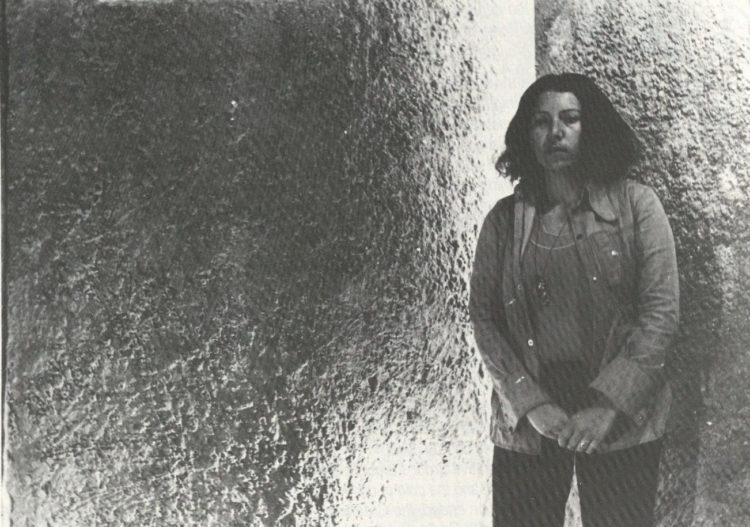

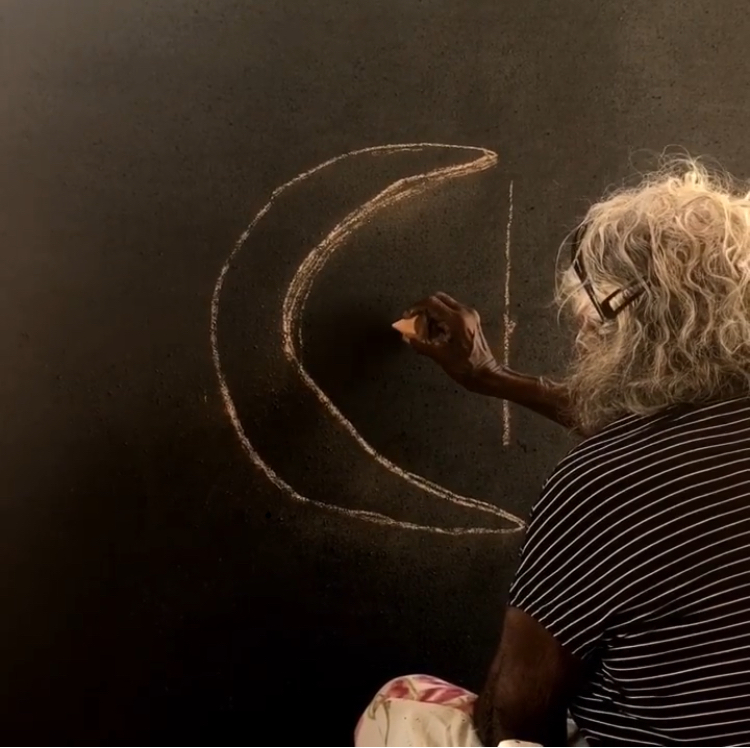

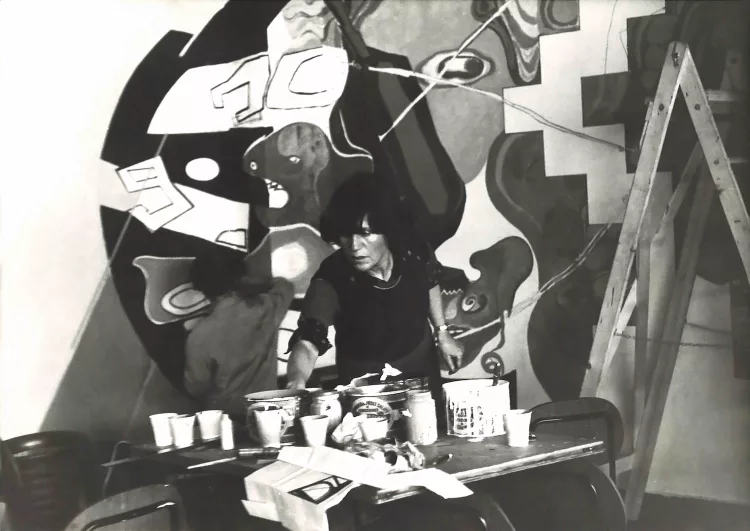

Some of the most powerful contemporary art engaging with the ecological crisis is that which draws on ecofeminism’s non-dualistic thinking and the deep customary insights of First Nations knowledges. In this article I consider work by three contemporary Australian artists whose aesthetics help facilitate the sensory recognition of the interrelatedness of the human and more than human, including the inextricable histories of colonial violence and environmental degradation, and position art as an inclusive platform for ecological communication and activism.

Ecofeminist philosophy explores the connections between the instrumentalisation of nature, the control of women, and the acquisition of scientific knowledge, all of which underpin modernity and the ideology of “progress”. As early ecofeminist Carolyn Merchant argues, “Nature cast in the female gender, when stripped of activity and rendered passive, could be dominated by science, technology, and capitalist production”.1 Ecofeminism critiques male-biased Western canonical views about women and nature and seeks alternatives and solutions.2

In Feminism and the Mastery of Nature, philosopher Val Plumwood proposes that Western culture has been systematically unable to acknowledge dependency on nature, the sphere of those it has defined as “inferior” others. As a result, the master discourse of reason has distorted the knowledge of the world and developed “blind spots” that threaten our survival. It is only through creating “a truly democratic and ecological culture beyond dualism”3 that we can transition to a sustainable future. In Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason, she reaffirms that “developing environmental culture involves a systematic resolution of the nature/culture and reason/nature dualisms that split mind from body, reason from emotion, across their many domains of cultural influence”.4 While sharing with deep ecology the belief that human life is just one of many equal components of a global ecosystem, ecofeminism asserts that one cannot disentangle anthropocentrism and androcentrism, nor critique the culture/nature dualism without providing a gendered analysis of how this dualism has functioned historically to legitimise the dominations of women and nature.5 By defamiliarising our conventional exchanges with nature, ecofeminism attempts to shift perceptions of other life forms – the more than human – as well as question received ideas about what it means to be human.

In recent decades environmentally conscious artists have embraced nature through humbling gestures of reconciliation, challenging the modernist belief in the dominance of “man” as rational being, along with its correlate, the environmental and social degradations of industrial capital. Ecofeminism informed many of these actions and highlighted the gendered dualistic thinking underpinning Western understandings of nature through inter-species and intersectional ecological actions.6 Ecofeminism has also informed recent scholarship and art practices associated with the “new materialism” that similarly realigns our understandings of life and agency. The ecofeminist imagination operating in such work materially confronts us with the different modalities of objects, setting us up for interactions that heighten our sense of the thingness of the world, including ourselves. As philosopher Jane Bennett suggests, such an approach allows passage to a more complex and more ethical view of what it means to occupy this planet, where human/object, human/environment and material/spirit are understood not as separate, but as integrated.7 With this understanding could come an enhanced political agency that is at home with mystery and uncertainty, and that operates holistically rather than privileging the place of the human subject, and in particular, reason.

Such an integrative conception of the human and more than human world is at the heart of many First Nations’ ways of being. In Australian Aboriginal belief systems, Country embodies the relatedness of land and culture: it is “a place that gives and receives life. Not just imagined or represented, it is lived in and lived with […] Country is a living entity with a yesterday, today, and tomorrow, with a consciousness, and a will toward life.”8 Country is the bedrock of culture, as the Earth is vested with the power and knowledge of ancestorial creator beings. This understanding of the intimate landscape necessarily recognises First Nations ownership and stewardship, an acknowledgment embedded in many First Nations’ artworks that link ecology and art to identity and cultural survival, and assert that loss of identity goes hand in hand with environmental degradation.

Julie Gough, p/re-occupied, 2022, mixed media, kayak, rocks video projection, sound, edited by Craige Langworthy, 7 min. 23 s. © Courtesy Julie Gough

Julie Gough (b. 1965) is a Trawlwoolway artist, writer and curator whose practice addresses the historical and ongoing trauma of the First Peoples of Lutruwita (Tasmania), including the experiences of her own family. Working with archives and stories, she makes films and installations that reinterpret particular places whose significance has been covered over or forgotten. In her works Country, as identity and as ecological phenomenon, are inextricable. In the most recent Biennale of Sydney (rīvus, 2022), which centred on the political agency of rivers and wetlands, J. Gough presented p/re-occupied (2022), a video projection with mixed media, including sound, kayak and rocks.9 The video follows the artist as she kayaks along several interconnecting rivers and tributaries in the Midlands of Lutruwita: her journey is a ritual of repatriation, to return facsimiles of cultural belongings, namely ancient stone tools long ago removed to museum collections, to ancestral waterways. At the same time the journey serves to return the First Nations names to these rivers, words “that respect their past and purpose and alliterate their flow since invasion, since colonisation. Survivors. Kin” – paranaple (Mersey River), panatana creek, tinamirakuna (Macquarie River) and lokenermenanya (Clyde River). According to the artist,

To be home, truly, on Country, is to become it. Particles. Substance of place. Belonging. Inhale. Exhale. Everything seems to swirl around, to gather, reform, then set out again […] When I kneel by a river on my island home, I don’t need to see my reflection to be grounded. Our Old People are in the wind, my imprint in that mud is the same repeated, over millennia, by family.10

Leanne Tobin, Ngalawan–We Live, We Remain: The Call of Ngura (Country), 2021, blown glass and hebel base, made in collaboration with glass workers Ben Edols and Katy Elliot, 23rd Biennale of Sydney: rīvus, 2022 © Adagp, Paris, 2023

Leanne Tobin (b. 1961) is a multidisciplinary artist of English, Irish and Aboriginal heritage, descended from the Buruberong and Wumali clans of the Dharug, the ancestral peoples of Greater Sydney. In her practice, which is often community based and collaborative, the desire to nurture Country brings together concerns around recovering stories of the Old People and caring for the more than human world. L. Tobin also featured in rīvus, with Ngalawan – We Live, We Remain: The Call of Ngura (Country) (2021), a sculptural installation, video and participatory weaving work that brought to life the Dharug story of Gurrangatty, the ancestral eel that long ago created the rivers and mountains. The work was spread across two locations to allow visitors to walk part of the path of the eel’s lifecycle; this is a phenomenal journey that sees the eels climb dams and creep over land as they follow their Songline to the Coral Sea, thousands of kilometres north, to spawn, adopting the colours of the river as they move between fresh and saltwater. The sculptural installation comprised of longfineels sinuously crafted in hand-blown glass, made in collaboration with glass artists Ben Edols (b. 1967) and Kathy Elliott (b. 1964), transparent and speckled to evoke the epic adaptive transformations the animals undergo. L. Tobin accompanied these with an animated video and a public workshop that allowed for more extended conversations about this creation story.

The eel’s adaptive transformations and survival in the wake of environmental degradation resulting from overdevelopment and pollution endemic to extractive capitalism, echo those of the Dharug people in the face of ongoing colonial violence. The Dharug are the custodians of Sydney’s Parramatta/Burramatta River, the traditional name translating to “where the eels lie down”. In this work L. Tobin recovers the name to affirm the relation between culture and the more than human:

Today, us Dharug move like eels between two worlds. We have morphed and adapted to new ways imposed on us. First to be colonised and first to lose colour, over time we’ve learned to adapt and become the river. Like eels we have never left. Where once we were hidden, our collective voice now rises to speak the truth.11

Patricia Piccinini, The Young Family, 2003, silicone, acrylic, human hair, leather, timber, 89 x 164 x 142 cm, Bendigo Art Gallery, Victoria, photo: Leon Schoots © Courtesy Patricia Piccinini

Portrait of Patricia Piccinini with Skywhalepapa (2020) and Skywhale (2013), hot-air balloons, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra © Courtesy Patricia Piccinini

V. Plumwood’s idea that the West’s master form of rationality has been unable to acknowledge its dependency on nature, relegating nature to the sphere of “inferior” others and distorting our knowledge of the world in a way that threatens our very survival,12 has been a key source of inspiration for Melbourne/Naarm-based artist Patricia Piccinini (b. 1965). Since the 1990s she has challenged conventional views of the duality of nature and culture through compelling material experiments that manifest in human/technology hybrids. Her sculptural objects question Western philosophical traditions privileging mind over body and the placement of the human subject and cognition at the apex of life on Earth. She imagines a world where such hierarchies no longer rule; a world in which machines and matter get amorous and feel family-bound (The Lovers, 2011; The Pollinator, 2018), where marvellous creatures evolved from the unpredictable interaction of disparate genetic material provide human comfort (Kindred, 2018), and where objects call out to us, reminding us of the limits of our power and the rich possibilities of listening to intelligences other than our own (The Naturalist, 2017). Her work brings to mind J. Bennett’s description of “vital materialists” whose “sense of a strange and incomplete commonality with the outside may induce (us) to treat non-humans – animals, plants, earth, even artefacts and commodities – more carefully, more strategically, more ecologically”.13

P. Piccinini’s exhibition, A Miracle Constantly Repeated (2021-2022) in the magisterial reclaimed ballroom above Flinders Street Station in Melbourne, was centred around the proposition that the distinctions we have made between nature and culture, human and animal, structure and wildness, are failing us and the planet. She observes, “We’ve inherited this idea that we are here and nature’s over there. That distinction? That boundary? It actually doesn’t work anymore.” Through her artwork, P. Piccinini asks:

How do we build our lives together with other, more-than-human animals? And how can it be a nurturing relationship? How can we have an understanding and experience of nature, which is not just about this very traditional idea of pristine nature, untouched by humans? Because that doesn’t exist, and the idea is not workable anymore.14

The practices discussed here evoke the ecofeminist desire to capture the irrepressible productive drive of the world, where organic and inorganic matter interact in complex ways that belie the assertion of human will, where the very notion of “an environment” comes into question, given it assumes a distinction between humans as agents and their context as passive. The work of First Nations artists Julie Gough and Leanne Tobin foreground the significant intersections between ecofeminist rethinking and deep ancestral knowledge of Country. As L. Tobin says,

Rivers teem with life. All living things in and along the river depend on the river. Water is fundamental in Mother Earth’s cycle of growth and regeneration. Rivers distribute that life force. The Old People understood our interconnection and reliance and their lives evolved around ensuring the health and continuation of that life force. We are all interconnected: what affects one affects us all.15

Carolyn Merchant summarises her central argument in The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology and the Scientific Revolution (San Francisco, CA: Harper and Rowe, 1980) in her later article, “The Scientific Revolution and The Death of Nature”, Isis 97 (2006): 513-533.

2

“Feminist Environmental Philosophy”, Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/feminism-environmental.

3

Val Plumwood, Feminism and the Mastery of Nature (London: Routledge, 1993), p. i

4

Val Plumwood, Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason (London Routledge, 2002), p. 4.

5

“Feminist Environmental Philosophy.”

6

Plumwood, Feminism and the Mastery of Nature, pp. 19–40.

7

Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), p. xi.

8

Deborah Bird Rose, Nourishing Terrains, Australian Aboriginal Views of Landscape and Wilderness (Canberra: Australian Heritage Commission, 1996), p. 7

9

The 7:23′ video was edited by Craige Langworthy and mins. The project was realised in accordance with Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) protocols (visual arts) and acknowledges the custodial interest of the First Peoples of Lutruwita (Tasmania) on whose unceded lands, riverways and estuaries this work was realised.

10

Julie Gough, “Absorption”, in rīvus: A Glossary of Water: 23rd Biennale of Sydney, eds José Roca and Juan Francisco Salazar (Sydney: Biennale of Sydney, 2022), p. 11.

11

Leanne Tobin, “Parramatta/ Burramatta”, in Rivus: A Glossary of Water, p. 360.

12

Plumwood, Feminism and the Mastery of Nature, p. i.

13

Bennett, Vibrant Matter, p. xi.

14

Patricia Piccinini, quoted in Stephanie Convery, “Patricia Piccinini brings Flinders Street station’s forgotten ballroom back to life”, The Guardian, 26 May 2021

15

Leanne Tobin, ‘Parramatta/ Burramatta’, in Rivus: A Glossary of Water, p. 359.

Dr Jacqueline Millner is Professor of Visual Arts at La Trobe University. Her books include Conceptual Beauty: Perspectives on Australian Contemporary Art (Artspace, 2010), Australian Artists in the Contemporary Museum (Ashgate, with Jennifer Barrett, 2014), Fashionable Art (Bloomsbury, with Adam Geczy, 2015), Feminist Perspectives on Art: Contemporary Outtakes (Routledge, co-edited with Catriona Moore, 2018), Contemporary Art and Feminism (Routledge, 2021 with Catriona Moore) and Care Ethics and Art (Routledge, 2022, co-edited with Gretchen Coombs). She has curated major exhibitions and received prestigious research grants from the Australian Research Council, Australia Council and Create NSW.

An article produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring.

Jacqueline Millner, "Ecofeminism in Contemporary Art: an Australian Perspective." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions Magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/lecofeminisme-dans-lart-contemporain-perspectives-australiennes/. Accessed 14 February 2026