Research

By a similar set of historical circumstances, a common spirit of collaboration and the desire for cultural renewal, artistic freedom and innovation in the region, three of Southeast Asia’s first independent artist-run spaces were established as the result of partnerships between local practitioners and foreign scholars and artists. Cemeti in Yogyakarta (Indonesia), Salon Natasha in Hanoi (Vietnam) and Reyum in Phnom Penh (Cambodia), founded in 1988, 1990 and 1998 respectively, arose out of a need for cultural renewal following periods of historical and political turmoil, in all three countries, before art institutions were founded in the region and when global art networks were still in their early stages. The three women, Mella Jaarsma (1960–), from the Netherlands; Russian-born Natalia (Natasha) Kraevskaia (1952–) and American Ingrid Muan (1964–2005), came to Southeast Asia to study, research or take part in an academic exchange, met kindred spirits and remained in their adopted countries, committed to their visions for Southeast Asian art. The three were pioneers in their interest in building a future for art in the region and contributed greatly to the development of contemporary art, each in their own way and within their chosen local environments. Some three or four decades since they first arrived in the region, their influence on the development of contemporary art cannot be underestimated. Indeed, it could be argued that their efforts to create spaces for learning, art making and exhibiting in an open and democratic manner were amongst the main impetuses behind the development of contemporary art in the region.

View of Cemeti Institute (facade) © Courtesy Cemeti Institute

Public Program Learning Nearby by Brigitta Isabella, 2025 © Courtesy Cemeti Institute

View of Water Resistance (solo exhibition of Ade Darmawan), 2024, photo: Kurniadi Widodo © Courtesy Cemeti Institute

Dutch born artist M. Jaarsma first came to Indonesia in 1984. She had studied art at the Minerva Academy of Fine Arts in Groningen and later attended the Indonesia Institute of Art in Yogyakarta. There she met Nindityo Adipurnomo (1961–). Thanks to a scholarship, Nindityo travelled to the Netherlands where they married before returning to Indonesia. In 1988, the two founded Cemeti Gallery, later named Cemeti Art House. The word cemeti is a Sanskrit word meaning ‘whip’ as in ‘whipping something into shape’. In an interview with Naima Morelli in Trouble Magazine, she explained that the couple wanted to start something completely different, an exhibition space that would be an information and documentation centre.1 At Cemeti, Mella and Nindityo started out by exhibiting work by their friends from school, such as Heri Dono (1960–) and Eddie Hara (1957–). At first, the space was quite small but it eventually expanded to include the Cemeti Art Foundation. The foundation evolved separately from the gallery, and in 2007 was renamed the IVAA or Indonesian Visual Art Archive.2 In the early and mid-1990s, Indonesia was still under martial law, governed by General Suharto. Artists, writers and other cultural workers were often subject to censorship until Reformasi, the political reforms that took shape after Suharto’s rule ended in 1998. Cemeti Art House offered a much needed space of intellectual freedom.

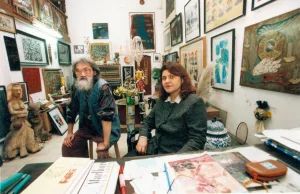

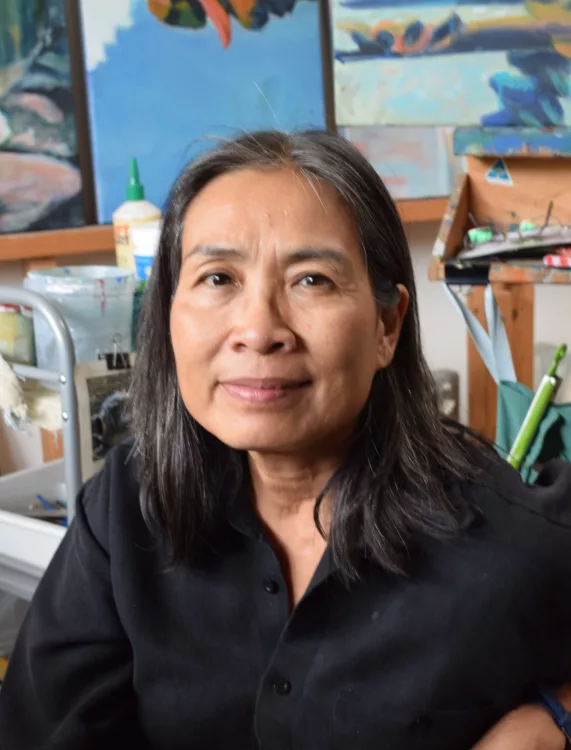

Russian-born N. Kraevskaia graduated from Leningrad State University and holds a PhD in Philology from the Pushkin Institute of Russian Language. She went to Hanoi in 1983 to work at the Pushkin Institute of Russian Language in Hanoi under the auspices of the Ministry of Education. She met the artist Vũ Dân Tân (1946–2009) and, as she recounted in conversation, fell in love at first sight.3 The two were married in November 1985, moving to the Soviet Union for a couple of years. It was there that Vũ Dân Tân witnessed first-hand the early stages of Glastnost and Perestroika initiated by then Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev (1931–2022). Although this period of increased openness and social and political restructuring resembled the economic reform policies of Đổi Mới instituted by the Vietnamese government in 1986, the artist considered that the situation in Vietnam had not allowed for complete artistic freedom. After returning to Hanoi in 1990, the couple founded Salon Natasha, modelled after Russian and French artistic salons or spaces, often in homes, where artists and intellectuals gathered to discuss cultural matters. The Salon was housed in Vũ Dân Tân’s home and studio at 30 Hàng Bông Street in the centre of Hanoi’s Old Quarter. Over the course of its fifteen years of operation, it organised over 70 exhibitions that were the fruit of collaborations, workshops and artistic experiments by a community of like-minded artists. Natasha and Tân were facilitators and supporters of younger artists’ work and the Salon operated as a space for free expression outside established exhibition spaces managed by the government. Since they operated from the private space of their home, they rarely applied for permission to show work – a requirement for most exhibitions. This gave artists a sense of safety and openness.

American artist and art historian I. Muan was a PhD student at Columbia University when she came to Phnom Penh in 1997 with a Dissertation Research Fellowship from the Social Science Research Council. She met Ly Daravuth (1969–) shortly thereafter. Daravuth was born in Cambodia and survived the Khmer Rouge genocide, but in 1980 left the country for France with his family. After studying at the Sorbonne, he returned to Phnom Penh in the mid-1990s. In 1998 they founded Reyum, which means ‘cicada crying’ in Khmer.4 Located opposite the National Museum in Phnom Penh, Reyum Institute of Arts and Culture provided a forum for research, preservation and the promotion of traditional and contemporary Cambodian arts and culture. I. Muan received funding from the Asian Cultural Council in 2000 and Reyum received grants from the Rockefeller Foundation and the Prince Claus Foundation in 2003. Reyum was a multipurpose institution but its main goal was to provide an open, flexible space for exhibitions, performances, research, training and education. According to the Rockefeller Foundation 2003 annual report, “one of its projects was an effort to reassemble Cambodia’s collective memory, gathering the stories, photographs and other artifacts of the country’s elder generation.”5 In 2000, it opened an art school to help disadvantaged young people new interest and skills. In the same year, it organised one of its most poignant and ground-breaking exhibitions, The Legacy of Absence, which reflected on Cambodia’s tragic past.6 In 2002 the same artists were invited to join an exhibition entitled Visions of the Future7 which, according to Ashley Thompson, was intended to counter Western audiences’ desire for representations of the Khmer Rouge period by Cambodian artists. Sadly, Ingrid Muan passed away in 2005 and the Reyum Institute ceased operations.

The three women arrived in the region at a time when their knowledge, expertise and generosity were much-needed. Coming from different countries and different backgrounds, they nonetheless shared a common trait: a desire to invest in a future for Southeast Asian contemporary art in a period when local institutions were unable or were failing to provide support for art and culture. Through their unions and collaborations with their partners, they succeeded in creating opportunities for local artists to advance their practices without relying on government funds. The collaboration earned them the trust of the community. Neither insiders nor complete outsiders, they bridged the gap between the international art world and local artists at a time when most of the world was ignorant of the potential of Southeast Asian artists. That said, their goal was not to promote Southeast Asian art to the rest of the world, but rather to nurture the talent of Indonesian, Vietnamese and Cambodian artists and to provide the freedom and space for independent experimentation and creativity. Most importantly, they enabled a spirit of exchange that would not have been possible without the creative and personal partnerships that they inspired. One cannot imagine contemporary Indonesian art without the pioneering efforts of Cemeti in supporting local artists. Thanks to N. Kraevskaia’s meticulous record keeping, in 2012, Asia Art Archive was able to digitise close to 5000 documents pertaining to Salon Natasha’s activities, testifying to the contributions that the space made to the growth of contemporary art in Vietnam.8 Finally, Reyum was more than a space for art making, instead becoming a site for reconciliation and an essential platform for enabling a discourse surrounding mourning the past and envisioning a future for Cambodian art.

Naima Morelli, “Mella Jaarsma: Give me Shelter”, Trouble, 1 December 2014, accessed 9 January 2025, https://www.troublemag.com/give-me-shelter-mella-jaarsma/.

2

Susan Ingham, “Cemeti – the alternative”, Indonesian Contemporary Art Reformasi, 18 November 2018, accessed 27 January 2025, https://reformasiart.com/blog/2019/11/18/cemeti-the-alternative/.

3

Personal Communication with Natasha Kraevskaia, 25 December 2024.

4

Ashley Thompson recounts how the directors originally named the institution “Situations”, in the French meaning of theatrical improvisation, but abandoned the term for lack of a Khmer translation. In her view, Reyum, “carries a melancholic association and gives expression to abstract, intangible nature”. The untranslated word, according to Thompson, evokes an inaccessible mourning for an unknown loss. Ashley Thompson, “Forgetting to Remember, Again: On Curatorial Practice and ‘Cambodian Art’ in the Wake of Genocide”, diacritics, Volume 41, Number 2, 2013, p. 86.

5

Rockefeller Foundation annual report, 2003, p. 27, accessed 9 January 2025, https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/Annual-Report-2003-1.pdf.

6

The Legacy of Absence: A Cambodian Story, Reyum, Phnom Penh (11 January–14 February 2000), Phnom Penh, Rasmey Angkor Printing House, 2000.

7

Visions of the Future, Reyum, Phnom Penh (31 December 2002–31 January 2003), Phnom Penh, Reyum, 2002

8

“Salon Natasha Archive”, Asia Art Archive, accessed 27 January 2025, https://aaa.org.hk/en/collections/search/archive/salon-natasha-archive.

Dr. Nora Annesley Taylor is the Alsdorf Professor of South and Southeast Asian Art at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She is the author of Painters in Hanoi: An Ethnography of Vietnamese Art (Hawaii 2004, reprinted by Singapore Press 2009) and co-editor of Modern and Contemporary Southeast Asian Art, An Anthology (Cornell SEAP 2012) as well as numerous essays on Southeast Asian and Vietnamese Modern and Contemporary Art.

Nora Annesley Taylor, "Southeast Asia’s First Independent Art Spaces and the Legacy of Pioneering Women Artists and Scholars from Europe and the United States." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/les-premiers-espaces-dart-independants-dasie-du-sud-est-et-le-legs-de-trois-artistes-et-chercheuses-pionnieres-deurope-et-des-etats-unis/. Accessed 18 February 2026