Research

Yuki Kihara, A Song About Sāmoa (Sāmoa no Uta) – Moana (Pacific Ocean), 2022, installation view, 5 piece installation; Samoan siapo, textiles, beads, plastic, Private collection, Naarm/Melbourne, Courtesy of Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries, Aotearoa New Zealand, © Photo: Gui Taccetti

During World War II, we bought sealed plastic packets of white, uncolored margarine, with a tiny, intense pellet of yellow coloring perched like a top just inside the clear skin of the bag. We would leave the margarine out for a while to soften, and then we would pinch the little ball to break it inside the bag, releasing the rich yellowness into the soft pale mass of margarine. Then taking it carefully between our fingers, we would knead it gently back and forth, over and over, until the color had spread throughout the whole pound bag of margarine, thoroughly coloring it.

I find the erotic such a kernel within myself. When released from its intense and constrained pellet, it flows through and colors my life with the kind of energy that heightens and sensitizes and strengthens all my experience.

— Audre Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic”

This brief essay proposes an anti-genealogy of experimental practice at the intersection of the poetics of the everyday and feminist alignments that take flight across temporal and geographic boundaries. To do so, it thinks with the notion of the “inappropriate/d avant-garde,” building on the work of artist and scholar Trinh T. Minh-ha (born in 1952). The examples upon which I draw have some connection with Japanese, feminist, queer, and transnational positionalities, though not every artist necessarily exemplifies or embodies all of these terms. Positing an anti-genealogy, I propose a framework for understanding experimental practice that self-consciously creates a nestling of artists in relation, but one that may involve direct social and material relations as well imagined ones and, significantly, what might be understood as retrospective assemblages of coalitions. Such assemblages become possible only in a framework wherein linear time’s dominance might be suspended, where coalitions cannot and will not wait for the completeness of linear time (from whose futures they were excluded in the first place).1 Instead, the anti-genealogical stance taps into ways of imagining coalitions that depart from linear narratives of experimental practice. What may follow are trajectories that are speculative and imaginative and, significantly, driven by techniques that, by taking wonder in error and the inappropriate, create pathways of experimental practice as “lines of flight,” in Madhu H. Kaza’s sense (which itself may be understood as an inappropriation of the phrase in the work of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari).2 In this essay, the lines of flight move from Audre Lorde’s work, rooted in the experience of Black American feminist writing, to 1960s Japanese experimental performance and beyond.

In the quote above, Lorde casts the erotic as a form of both power and “sharing of joy”—which might encompass the “physical, emotional, psychic, or intellectual.”3 Lorde’s essay invites experimental practice to be considered not just as an artistic practice, but as a powerful way of relating to the world through the inseparable connection between art and everyday life. Lorde’s writing insists on being heard through and across forces that seek to undermine her status as poet and as human based on any racial, gendered, sexual, and class difference. She insists on sharing stories that depart from normative standards as beautiful and powerful in their own terms. Her writing makes it impossible to read the passage about margarine as a story of lack. In Lorde’s words, spreading the rich yellow pellet delivers a joy that is sensual, emotional, and also subversive, in that the yellow coloring serves no nutritional or functional value. The pellet’s sole purpose, in its softening and kneading, is to fabricate a feeling of richness through the senses—visual, tactile, perhaps even olfactory—with pleasure increasing through the delayed gratification of the process.

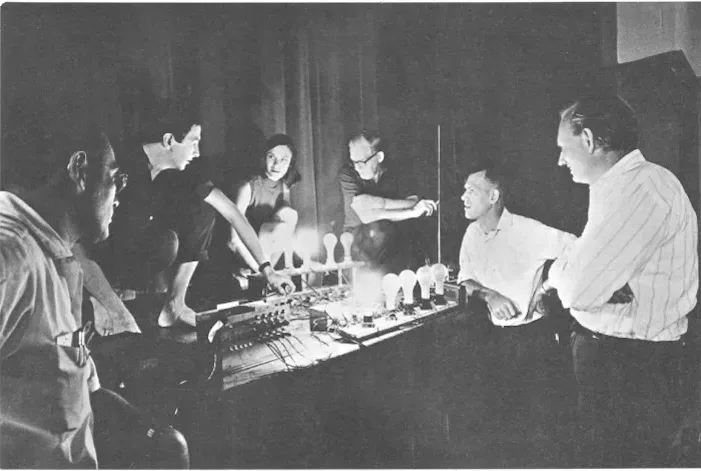

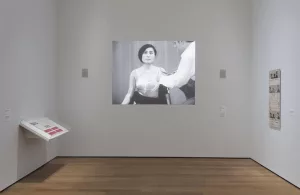

Installation view: Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960–1971, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, May 17–Sep 7, 2015, Courtesy: The Museum of Modern Art, New York (The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift) / Scala, Florence.

Mieko Shiomi, Water Music from Fluxkit, 1965, Glass bottle with plastic dropper and offset label, 8.8 × 3.4 × 2.9 cm, Collection: the Museum of Modern Art © 2025 Mieko Shiomi

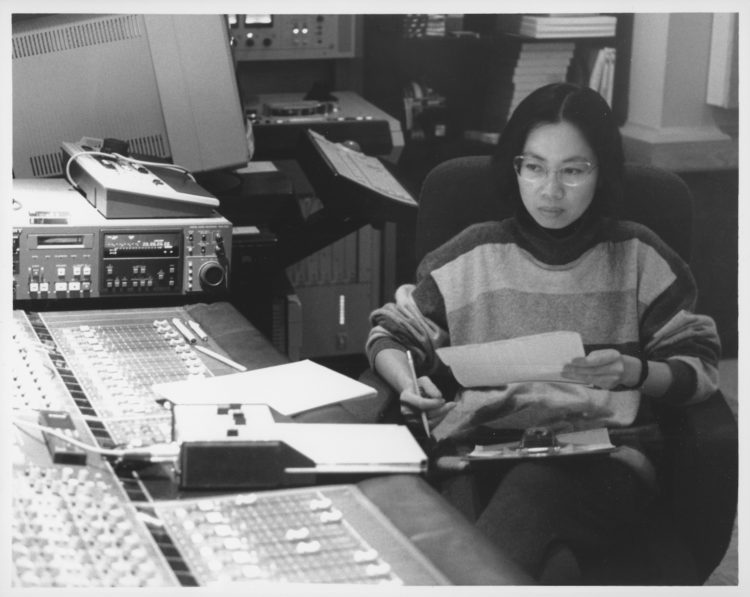

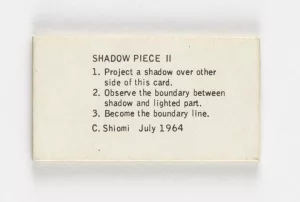

In the context of the Japanese avant-garde, performances based on everyday gestures and sounds, like hammering a nail or sitting (Yoko Ono, born in 1933), or else employing domestic appliances, bottling water in a jar, or instructing the audience to observe a shadow (Mieko Shiomi, née en 1938) may, on the surface, seem absurd. Such works certainly deviated from what most concertgoers expected of a musical performance in a recital hall or an art-museum gallery. Trinh Minh-ha’s concept of “inappropriate/d Others” sheds light on relations of power that work through systems of inclusion and exclusion, where the inappropriate/d Other, as subject, operates from the position of “not quite other, not quite the same,” located in an “elsewhere… within here” in relation to the hegemonic subject.4 I work with her term to think about the degrees to which experimental artistic practices in Japan are simultaneously appropriate according to metrics associated with the so-called West and other dominant paradigms, but also appropriated from them as well as inappropriate (or, put crudely from a dominant perspective, “wrong”).5 But Trinh’s formulation includes a third term—the inappropriated. For example, from the perspective of a Japanese artist working in the field of experimental performance, the music they created by appropriating the European and American avant-gardes was “inappropriated” insofar as their practices could not but also would not be subsumed into the international avant-garde by European and American metrics. To be inappropriate/d in all three senses was both a condition and affordance of the Japanese avant-garde’s transnational legibility.

Mieko Shiomi, Shadow Piece II, 1964, Mailed envelope, containing double-sided offset card, sheet: 2.6 × 4.8 cm; overall: 10.4 × 13 cm), Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, Courtesy: The Museum of Modern Art, New York (The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift) / Scala, Florence

At the same time, these movements and relations cannot be limited to a national framing, Japanese or otherwise. For example, when Shiomi Mieko instructs her viewers in Shadow Piece to observe light bouncing off the tiny fibers of her parlor room couch, there is a shared feeling of wonder in the ordinary. What transpires next is a shared sense of wonder between the artist and the observer, who becomes an active participant. This way of engaging with the everyday connects as much to Audre Lorde’s investment in everyday erotics as it does to the broader concerns of the 1960s Japanese avant-garde.

To be inappropriate/d from the perspective of a transnational, intersectional perspective is also a practice of combining, remixing, transforming, and at times misreading, which culminates in an altogether new expression. Here, I am thinking of early twentieth-century Japanese poet Sagawa Chika (who was also a well-regarded translator of Western modernist poems, including those of James Joyce), of whom Sawako Nakayasu writes: “Chika’s work lived at the intersection of languages.”6 Nakayasu’s choice of the term “intersection” also possibly links the notion of intermedia and intersectionality vis-à-vis Sagawa’s linguistic transculturalism as potential sites of gendered and racialized tensions and empowerment. Living at the intersection between languages, the practices that take place are not really about “code switching,” which implies a duality between either a Japanese avant-garde or a Western one. As Nakayasu writes of the modernist poets in the 1920s, many “struggled with their ambivalence about Western influence, [while] Chika seems to have taken ownership of this tension.”7 An intersectional understanding of translation creates a connection between Chika and Ono, who each simultaneously negotiated Western and Japanese aesthetics, thought, and historical lineages, articulated by their own lived experience through prisms of race and gender.

Miya Masaoka, Vaginated Chairs, 2017, dimensions variable, installation view: Kunst Museum Bonn, Germany, © Photo: Peter Kiefer, Courtesy of the artist

Yuki Kihara, A Song About Sāmoa (Sāmoa no Uta) – Moana (Pacific Ocean), 2022, installation view, 5 piece installation; Samoan siapo, textiles, beads, plastic, Private collection, Naarm/Melbourne, Courtesy of Yuki Kihara and Milford Galleries, Aotearoa New Zealand, © Photo: Gui Taccetti

Such lines of flight of the inappropriate/d enable frameworks in which further connections, from Chika Sagawa to Ono and Shiomi, expand as well as test the limits of what “Japanese” and “feminist” might mean; this particularly in the context of such work as that by Japanese-American composer and sound artist Miya Masaoka. Her Vaginated Chairs (2018) invites us to imagine and experience a sonic space when listening with our “third ear.” It also gives language to understand the layers of gender, power, and colonial representation in the work of Sāmoan-Japanese artist Yuki Kihara, or the coming together of punk, kabuki, and lesbian and trans experimental theater in the production of Drum of the Waves of Horikawa (2006). Each of these practices are deeply rooted in the histories that they engage, while also making moves that inappropriate/dly take lines of flight with, and from, spaces of the mundane that shape materials of their work.

From the perspective of the 21st century, it is tempting to reframe the group work discussed here—assembled provisionally through the inappropriate/d’s weak ties—as foundations of a feminist avant-garde, given their investigations into the body, the politics of domesticity, and their multifaceted critiques of the (male-dominated) art world’s conventions through which they moved. Yet, as artists who began their work from the early twentieth century to the 1960s, “feminism” and “feminist art” were not necessarily movements or terms that Chika, Ono, or Shiomi explicitly embraced. Their early work preceded any major international or domestic movement self-identified as feminist. In this sense, I suggest that their “feminism” might also be understood as a part of a broader mood, critiquing hegemonic forms of power that shaped artistic and public life in the postwar Japanese and transnational environments in which they worked. As much as their work may be viewed as political acts, they also harbor a multitude of potentialities—what Raymond Williams called “structures of feeling”––for ideas, concepts, and movements yet to be fully crystalized into labels like “transnational feminism.”8 If the weakness of structures of feeling are in their not-yet-fully formed nature, their power is in offering strength through potentiality and hope for further lines of flight.

Here I am thinking about the work of Rasheeda Philips and her work with Black Quantum Futurism in work such as Rasheedah Phillips, “Race Against Time: Afrofuturism and Our Liberated Housing Futures,” Critical Analysis of Law 9, no. 1 (2022): 16–34.

2

Madhu H. Kaza, Lines of Flight (New York: Ugly Duckling Presse, 2024). Kaza’s “lines of flight” echoes the notion of the line of flight, a key theoretical move in the work of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari that foregrounds a notion of multiplicity to disrupt fixed structures and hegemonic narratives. In my understanding of Kaza, her lines of flight as a gesture rests in the specific act of translation, of with an insistance on making connections, against time, and as a generative move of meaning making through error as an act that challenges expectations of the monolingualism, and the idea of a perfect translation.

3

Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Berkeley: Crossing Press, 2015): 56.

4

T. Minh-Ha Trinh, The Digital Film Event (New York: Routledge, 2005): 125–26.

5

T. Minh-Ha Trinh, ed., “She, the Inappropriate/d Other,” special issue, Discourse 8 (1986–87); T. Mihn-ha Trinh and Marina Grzinic, “Inappropriate/d Artificiality,” in The Digital Film Event, 125–34.

6

Chika Sagawa, The Collected Poems of Chika Sagawa, trans. Sawako Nakayasu (Ann Arbor: Canarium Books, 2015).

7

Sagawa, Collected Poems, xviii.

8

Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977).

9

Raymond Williams, Marxism and Literature, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1977.

Miki Kaneda’s work centers on themes of transcultural movements and the entanglements of race, gender, and empire in experimental, avant-garde, and popular music. Her recent projects have also examined the connections between musical performance and labor in contemporary new music in the United States. Her current book project, titled Transpacific Experiments: Intermedia Art and Music in 1960s Japan, is forthcoming from the University of Michigan Press. Her writing appears in Jazz and Culture, The Journal of Musicology, ASAP/Journal, Twentieth-Century Music, the San Francisco Chronicle, and post.moma.org, where she was a founding co-editor. She is Associate Director of the Center for the Humanities at New York University.

Miki Kaneda, "Margarine and the Erotic Everyday: An anti-genealogy of inappropriate(d) others." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/margarine-et-erotisme-une-anti-genealogie-de-lautre-inapproprie/. Accessed 27 February 2026