Research

Guyana’s migration histories and contemporary stories remain largely invisible within both academic and public spheres. In lieu of this limited scholarship and as a curator whose work examines the nexus of art and migration, I rely on the artistic production of Guyanese artists and those in the diaspora to centre our art and migration narratives. On this occasion, I would like to share the work of four key artists with whom I have been in partnership in my curatorial practice and scholarship in our mutual commitment to telling Guyana’s migration stories, especially when those stories have been misrepresented or unexamined. These artists and their equally compelling work were featured in my book, Liminal Spaces: Migration and Women of the Guyanese Diaspora (2020)1, a collection of art, memoir, creative nonfiction, poetry, photography, art and curatorial essays. In dialogue with our symposium’s theme, On the Edge of Visibility, these artists are doing two particular things: pushing back against what Nigerian-born author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie calls “the dangerous single story” of a place and engaging Tina Campt’s provocation of “listening to the image”, particularly the images within their family archives.

In her 2009 TED Talk, The Danger of a Single Story2, C. Adiche pushes back against the story of Africa as “a single story of catastrophe”. I often open my course Case Studies on Curatorial Activism by showing my students this talk, as I have found it to be an effective pedagogical tool, especially as we, curators in service to the Global South, discuss this evergreen question: What is a curator’s responsibility to place? “The [dangerous] single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story,” continues Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Guyana too has been subjected to a dangerous single story. The global representation of Guyana has centred on violence, political corruption, poverty, trauma and mass exodus of its citizens, as exemplified by the 2018 New York Times article “The $20 Billion Question for Guyana”.3 Taking inventory of the visual language in the lead paragraphs alone, we are given the following framing of Guyana: vast watery wilderness, dirt roads, snaking rivers, children playing naked, muggy heat, clapboard town, forgotten by time, blackouts, plague in the cities. One wonders whether this is 21st century journalism or a passage from Joseph Conrad’s The Heart of Darkness (1899)? This is how Guyana is represented on the world stage. More importantly, it continues to be a global malpractice that the majority of the stories told about us, are not by us, which in itself is its own kind of unique danger.

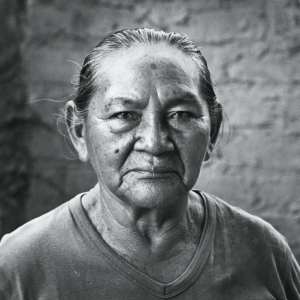

Khadija Benn, ‘Anastacia Winters’, from the series ‘Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerindian Women’, 2017-ongoing, digital photography. Courtesy of the artist

Khadija Benn, ‘Mickilina Simon’, from the series ‘Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerindian Women’, 2017-ongoing, digital photography. Courtesy of the artist

C. Adiche’s words about the dangerous single story of a place crack open the question: what is the dangerous story being told of Guyana – of its community, of its families, and of Guyanese women in particular – that must be countered? Two artists, Khadija Benn and Christie Neptune, poignantly engage with this question in key bodies of work that wrestle with countering the ways in which Guyanese women are rendered invisible. In her ongoing portraiture series, Those Who Remain: Portraits of Amerindian Women (2017–), K. Benn, who is based in Guyana, works closely with Indigenous communities living in remote places to which most Guyanese rarely have access. The elder Indigenous women who make up this series are mothers, grandmothers and great-grandmothers whose descendants have long migrated to neighbouring countries such as Venezuela and Brazil, to North America or to nearby Caribbean islands. However, these women have either made the choice to stay or are unable to leave Guyana. Their stories implore us to ask, “When migration swirls around us, what does it mean to remain?”

The crux of my work on the nexus of art and migration is to shift the way migration is misrepresented as a one-way street. Instead, I offer the perspective of two spectrums of the migration arc: the ones who leave and the ones who are left. That to leave a place we must reconcile ourselves to leaving others behind. These Guyanese elder women, some of whom were born as early as the 1930s, have witnessed Guyana evolve from a colonised British territory, to an independent state, to a nation working to carve out its identity on the world stage. Their stories underscore that we cannot talk about the migrant self without talking about the relationship to who and what gets left behind.

Christie Neptune, Memories from Yonder, 2015, diptych of archival inkjet prints. Courtesy of the artist

Christie Neptune, Memories from Yonder, 2015, diptych of archival inkjet prints. Courtesy of the artist

Memories from Yonder (2015) by New York City-based artist C. Neptune engages with the first node of the migration arc – the ones who do leave. This body of work is focused on Ebora Calder, a Guyanese-born elder who migrated to New York City in the late 1950s and spent her working years as a home care aide and nanny. This work speaks to the generations of Guyanese women, who in the last sixty years have been part of a significant migration from Guyana to New York. Memories from Yonder incorporates distorted photography and video where C. Neptune digitally weaves together portraits and text in Guyanese patois from conversations with E. Calder. Her words, “I had a hard time adapting to this culture” allude to the isolation that underscores her experience as an immigrant in New York’s blue collar workforce. That isolation and invisibility can also be read in the veiling and obscuring within the portraits. There is also an intentional opacity deployed by C. Neptune in the work as E. Calder is depicted in the slow, rhythmic act of crocheting a red bundle of yarn – an object meant to be amorphous.

In her book Listening to Images (2017), T. Campt urges that we must go beyond what we see in the image and instead listen to and for “unsayable truths” in them “to perceive their quiet frequencies of possibility”.4 I look for those unsayable truths in the lead image for that New York Times article, “The $20 Billion Question for Guyana”, and its adjoining caption telling us that these are Guyana’s fishermen, who toil in one of “the poorest countries in South America”. Yes, the photograph conveys so much about the nation’s labour landscape, our economy and our ecology. Yet, there in the photograph is both its punctum and, as T. Campt says, a “quiet frequency” – a Hindu jhandi flag planted firmly on one of the fishing boats. If we were listening to the image, we might see and hear that in the midst of another gruelling day of toil, there is an object of spirituality that provides a lens beyond what these men do and into who they are.

“Angela DeFreitas (grandmother) in Georgetown poses with a wedding cake she made and decorated”, ca. late 1960s. © DeFreitas Family Collection, Courtesy of Erika DeFreitas

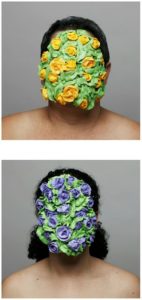

In tandem with T. Campt’s charge that we must listen to the image, Erika DeFreitas and Farihah Shah, both Guyanese Canadian artists, engage with this question: in the family archives, how does one listen for the silences, gaps, absences, erasure, losses, opacities? In their bodies of work, both artists listen to the images within their own family archives to speak to their maternal histories. E. DeFreitas’ portraiture series, The Impossible Speech Act,5 is focused on the sacred act of passing on a closely held family craft of baking cakes through three generations of DeFreitas women and across two continents. The black and white photograph shows E. DeFreitas’ grandmother, Angela – a skilled baker who sold cakes from her home in what was then British Guiana in the late 1950s. Drawing on the teachings of her grandmother, E. DeFreitas and her mother take turns in a series of performative actions, both poetic and playful, to hand-fashion face masks out of green, yellow and purple icing to make these sculptural objects of flowers and leaves. In this work, these three women are simultaneously subjects and collaborators across geographies and across time.

Erika DeFreitas, The Impossible Speech Act, (detail), 2007, archival inkjet print. © Erika DeFreitas. Courtesy of the artist

Reading this work through an art and migration lens, what I found compelling is how it is pushing against the trope of a relationship marked by tension, distance and separation between first-generation daughters and their immigrant mothers (and even grandmothers). This is a trope we see quite often in Caribbean migration literature, for example in Jamaica Kincaid’s short story Girl (1978). Instead, in this work, E. DeFreitas frames immigrant mothers as one of our greatest collaborators. We are shown how, as daughters of Guyana, we reach to and rely on our mothers as co-makers and co-authors (and even co-bakers) both in our lives and in our art making.

Farihah Aliyah Shah, Looking for Lucille, 2017–22, installation view. In Are We Free to Move About the World: The Passport in Contemporary Art, Tallahassee, Museum of Fine Arts, Florida State University, 2 February–20 May 2023, curated by Grace Aneiza Ali. Image courtesy of Grace Aneiza Ali

Lastly, in the multi-media and ongoing installation Looking for Lucille (2017–2022), F. Shah centres her grandmother’s Guyanese passport to construct an archive. As migration objects, passports are visceral and charged. I have both a personal and curatorial obsession with them as I understand their great paradox – they have the ability to grant us freedom of movement, as well as significantly curtail that movement. When we were in Guyana, my family waited almost a decade for passports. In Looking for Lucille, part of my recent exhibition Are We Free to Move About the World: The Passport in Contemporary Art (Museum of Fine Arts, Florida State University, Tallahassee, Florida, February–May 2023), F. Shah deconstructs her grandmother’s Guyanese passport and urges us to think through critical questions: what can a passport reveal about a migratory life? What determines a life worthy of an archive? Engaging with this work allowed me to reflect on my mother’s story who, as a Guyanese woman, received her first passport and was able to travel abroad for the first time in her late 30s. If we are to listen to these passports of Guyanese women, we can hear the dispossession that still exists for many women in the Caribbean today – women who are not free to move about the world or who are made to wait for that freedom.

Grace Aneiza Ali (ed.), Liminal Spaces: Migration and Women of the Guyanese Diaspora. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2020, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0218.

2

“The danger of a single story – Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie”, TED Talks, July 2009 : https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story.

3

Clifford Krauss, “The $20 Billion Question for Guyana”, The New York Times, 20 July 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/20/business/energy-environment/the-20-billion-question-for-guyana.html.

4

Tina Campt, Listening to Images (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017).

5

Grace Aneiza Ali (ed.), Liminal Spaces: Migration and Women of the Guyanese Diaspora. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2020, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0218.

Guyanese-born Grace Aneiza Ali is a curator and assistant professor in the Department of Art and Art History at Florida State University and is a 2024/2025 Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Fellow at The Huntington. As a curator-scholar of contemporary art of the Global South, her curatorial research practice examines the links and slippages at the nexus of art and migration. G. Ali specialises in art of the Caribbean Diaspora with particular attention to her homeland, Guyana. Her book, Liminal Spaces: Migration and Women of the Guyanese Diaspora (2020) explores the art and migration narratives of women of Guyanese heritage. G. Ali serves as Editor-in-Chief of the College Art Associations’ Art Journal Open and member of the Board of Advisors for British Art Studies.

This essay has been adapted from remarks given by Grace Aneiza Ali at the international symposium On the Edge of Visibility, convened by Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions (AWARE) and Women Photographers International Archive (WOPHA), and held at the Pérez Art Museum Miami on Thursday 19 October 2023.

Grace Aneiza Ali, "Centering Guyanese Women’s Art and Migration Narratives." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/mettre-au-coeur-du-recit-lart-et-les-histoires-de-migration-des-femmes-guyaniennes/. Accessed 3 July 2025