Research

Kōran Tōru, Tropical Fish, 1939, color on paper, two-panel folding screen, 168.5 × 185.6 cm, Collection of SEKI Kazuo

Introduction

The preeminent woman artist of modern Japan is undoubtedly Shōen Uemura (1875–1949). Moreover, outside of S. Uemura, there was a not inconsiderable number of women artists active in every region of Japan, though few of their names remain known to us today. In recent years, efforts have begun to honour those modern women artists who have up to now been carelessly omitted from art history. Traces of these women artists are recorded in the results of public exhibitions—such as the Bunten (the first iteration of the Japan Fine Arts Exhibition), which was founded in 1907—in the listings of contemporaneous artist directories1 and in the articles of newspapers and magazines from the period. In some cases, works have been discovered with a “woman (女)” mark affixed at the end of a pseudonymous signature; in others, we have been fortunate to have works identified by surviving family members. Many women get married in the early stages of developing their painting careers, and many of them have their work stagnate or find themselves leaving the vanguard of the art world amid the socially accepted idea that they should prioritize home and family. Not only are these women’s pseudonyms not their real names, when they marry, their surname changes, and gathering information about them becomes impossible as data about their movements disappears. Only a small portion of women—those with favourable circumstances, such as an understanding husband—overcome the great hurdle of marriage to become successful as artists.2 For that reason, some women artists did not marry or chose to get divorced. In contrast to men, marriage constitutes a large gamble for women artists that can threaten their artistic career.

Artists in the Three Cities

The centres of modern Japan’s art world were Tokyo and Kyoto. If we examine the selection results over a twenty-five-year period in the early days of the Bunten Exhibition, from its founding in 1907 to 1932, we find that 90% of the nihonga (Japanese-style painting) artists who were selected had residences in these two cities.3 The prominent artists who served as judges lived and worked in Tokyo and Kyoto and trained many pupils there. On the other hand, the number of artists from the commercial city of Osaka who were selected for the exhibition was very low at less than 5%. It was a disadvantage to pursue art in Osaka, a city without the backing of any influential artists, and many people left their hometown to study in Tokyo or Kyoto.

Next, if we consider the gender ratio of the selection for the aforementioned twenty-five-year period, 96% of the nihonga artists who were selected were men, while the proportion of women was extremely low at 4%. Furthermore, if we narrow our focus to this 4% of women selectants and look at their places of residence, we do not see a large difference between women artists in Tokyo, Kyoto and Osaka. For the particulars on this topic, I yield to the exhibition catalogue of the 2023–2024 Osaka in the Eyes of Women Painters show, which I curated, but from the end of the Meiji era (1868–1912) to the early days of the Shōwa era (1926–1989), women artists in Osaka were nearly equal to those of Tokyo and Kyoto in terms of their selection rates for works and official exhibitions.4 If we restrict ourselves to the Taishō era (1912–1926), the number of selectants from Osaka surpassed that of Tokyo and Kyoto. This data substantiates the fact that, while Osaka was a lesser city in terms of the art world as a whole, when it came to women artists, it more than held its own.

Seien Shima, Self-portrait, 1924, color on silk, framed, 42.4 × 34.7 cm, Osaka Municipal Museum of Art

Seien Shima, Pipe en vermillon avec tige en bambou, 1934, couleur sur papier, rouleau suspendu, 88 × 131,6 cm, musée municipal d’Osaka

Chigusa Kitani, Joruri Boat, 1926, color on silk, 175.3 × 360 cm, Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka

Seien Shima

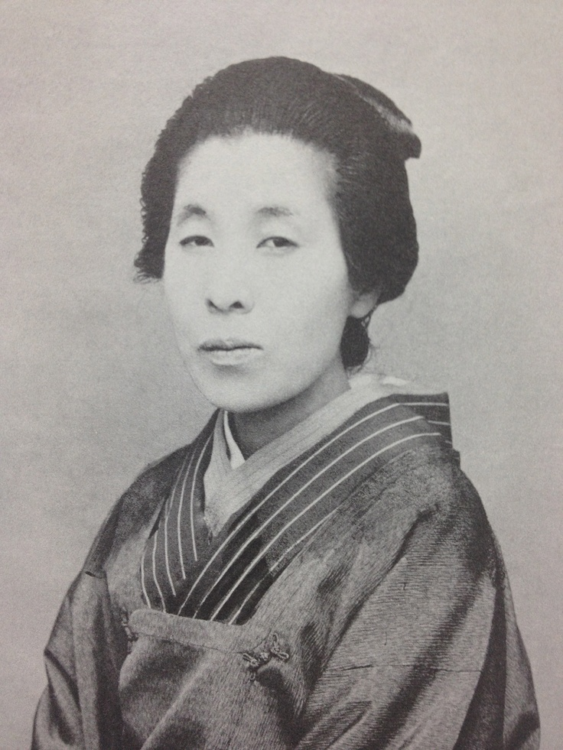

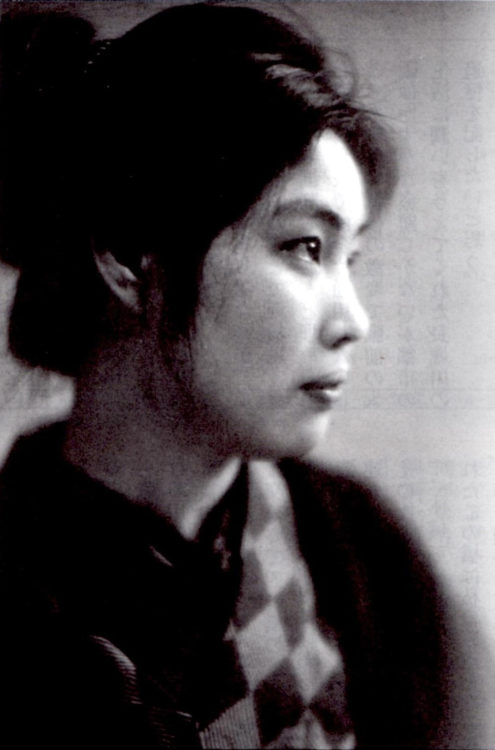

The artist who created the catalyst for the emergence of numerous women artists in Osaka was Seien Shima (1892–1970). Born in Sakai City, Osaka Prefecture, S. Shima is distinctive for her experience of growing up in a household where both her father and brother made their living as artists. First, she self-studied painting at home and did not learn from a designated instructor. Additionally, her experience differed from that that of the highly educated daughters of affluent households, who studied painting as part of their accomplishment lessons. Intending from the outset to pursue a painting career, the 20-year-old Seien rose to fame in 1912 when her bright and vivacious painting of beauties (bijinga), Evening in Soemon-chō (Soemon-chō no yūbe), was selected for the 6th Bunten Exhibition. Around the same time, Kyoto’s S. Uemura and Tokyo’s Shōen Ikeda (1886–1917) were actively working as bijinga artists, and all three of them—Osaka’s S. Shima included—made use of the pen name “En 園.” For that reason, they were collectively dubbed “the three ‘En’ of the three cities”—a most fortunate debut. Afterwards, S. Shima’s achievements, which she continued to amass one by one, served as huge encouragement to young women who enjoyed painting. Sparked by the efforts of S. Shima, a familiar figure who overcame the three disadvantages of being a “young, unknown woman of Osaka” to make her entrance in the art world, hopeful women aimed to enter the Bunten exhibition one after another. Together with Kōen Okamoto (1895–?), Chigusa Kitani (né Yoshioka; 1895–1947) and Kayō Masamoto (1893–1961)—each of whom had successfully entered the Bunten from Osaka—S. Shima formed the Onna Yonin no Kai (The Four-Woman Society) and proceeded to hold exhibitions. Furthermore, women gathered at S. Shima’s private painting school from the local region and from far off locales like Tokyo and Kochi in the hopes of becoming her pupils. The woman-only painting school also had merit for parents, who could send their unmarried daughters there with confidence. The Osaka art world was devoted to a bijinga painting lineage that centred on Tsunetomi Kitano (1880–1947), and S. Shima, too, worked in active proximity to him, but they were on equal terms with one another and not in a teacher-student relationship.

S. Shima made her presence known through the production of a succession of unique paintings of women that did not fit the bijinga mold, including Untitled (Mudai; 1918; Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts) and Fragrance of Aloeswood (Kyara no kaori; 1920; Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts). Though she had intended to remain single and devote herself to her painting career, she married a man chosen for her by her father and brother in late 1920. Afterwards, she fell into a slump and retired from the forefront of the art world, but she continued to produce excellent work like Self-Portrait (Jigazō; 1924; Osaka City Museum of Art), which realistically depicts her own exhaustion, and in the early Shōwa period, her style shifted to a lighter mode of expression. C. Kitani, who had participated in the Onna Yonin no Kai, also opened a private painting school after marriage and trained many members of the next generation. Along with Ikuta Kachō (1889–1978)—who will be discussed below—C. Kitani occupied a leadership position among the women artists of Osaka. As for S. Shima, her active period was short, but the era of Osaka’s women artists would not have dawned without her.

Seiran Kawabe, Noble Beauties, 1889, Hanging scroll, ink and colour on silk, 154.1 × 70.7 cm, Collection: Kayuki Memorial Museum of Practical Women’s University

Kōran Tōru, Tropical Fish, 1939, color on paper, two-panel folding screen, 168.5 × 185.6 cm, Collection of SEKI Kazuo

Nanga Art

Women have long been active in the nanga (Southern-style painting), or bunjinga (Literati painting), genre, which features no artists circles or hierarchies, and Osaka has a flourishing history as the centre of western Japan’s nangatradition. Women nanga artists who were active across the country include Kakei Atomi (1840–1926), Shōhin Noguchi (1847–1917) and Kagai Hatano (1863–1944), each of whom was from Osaka. Seiran Kawabe (1868–1931), a local artist with a long history of activity, is worthy of special mention. The daughter of a respected family, S. Kawabe cultivated a pursuit of scholarship and painting early in life and avidly continued painting even after her husband married into the family, being blessed with multiple patrons and gaining fame on par with S. Uemura. She coached many younger women, but lamented how difficult it was for modern women to acquire an interest in the Chinese classics and poetry indispensable to the nanga tradition. With the changing of the tides, younger women may have preferred bijinga to nanga, which required a profound cultural understanding of literature and scholarship.

On the other hand, within the new trend of “New Nanga,” artists created fresh works with modern subject manner, as in the case of Kōran Tōru’s (1906–1982) Tropical Fish (Nettaigyo; 1939; Seki Collection). K. Tōru married a yōga (Western-style painting) artist and continued her painting career for many years but became famous after the Second World War as a television life counsellor and presenter. She left behind numerous writings from which we can learn much about women’s culture and the art world in prewar Osaka.

Bird and Flower Paintings

In Japan, it is customary to replace the paintings in tokonoma alcoves in accordance with the seasons, and the paintings used to decorate tokonoma are formal nanga paintings or bird-and-flower pictures (kachōga) that elicit the charm of the seasons.5 These elegant, refined bird-and-flower pictures were considered appropriate for women, and there was a high demand for them at private painting schools. At the same time, however, the representative bird-and-flower painters of Osaka, like Chokujō Fukada (1861–1947) and Kōen Niwayama (1869–1942), did not enter their work for display in public exhibitions like the Bunten. In the commercial city of Osaka, these artists received a steady stream of financial support from wealthy local patrons and did not need to garner national reputations. Consequently, records on these artists are virtually non-existent, and information about women bird-and-flower painters is likewise scarce, though they are thought to have been primarily daughters of respectably families who developed a taste for painting during accomplishment lessons. Bird-and-flower painting schools were sex-segregated, and students learned gradually by copying picture albums painted by their teachers. At C. Kitani’s painting school (the Yachigusa Kai), bird-and-flower painting was taught alongside figure painting,6 and the artist opened her own garden so that her female students could sketch without restraint.

Kachō Ikuta

Born in Osaka as the third daughter of a literatus, K. Ikuta made a late debut in the art world when she was first selected to present her work at the Teiten (Imperial Academy of Arts exhibition) at the age of 36. The following year, however, at the 7th Teiten Exhibition in 1926, she became the first woman to be honoured with a special prize for her work Tenjin Festival in Osaka (Naniwa Tenjinmatsuri; whereabouts unknown). From that point on, she became a major women artist in Osaka and enjoyed a long career in the fields of painting and haiku. K. Ikuta painted the history and customs of Osaka and Japan, and her ample knowledge was the result of her having studied under several distinguished teachers, such as the painting master Tatehiko Suga (1878–1963). Her paintings, which take festivals and traditional events as subject matter, vividly reproduce scenes based on historical fact, depicting crowds of people in a detailed, colourful and lively manner. K. Ikuta’s attachment to the local region of Osaka was strong, referring to her work as “regional art.” Remaining single, she continued to exhibit her work at the Japan Fine Arts exhibitions, even after the Second World War, and was loved and respected by those around her for her superior artistic talent and gentle manner.

Conclusion

Osaka, with its lack of influential male artists and weak art world foundation, nevertheless witnessed the advent of numerous women nihonga artists.7 Though only a handful were able to continue a lengthy career, and their prosperity may have been a fleeting phenomenon, a wide range of women painted out of preference, and the individuality visible in their works has a charm that differs from the trends of the art world’s centre. Today, Osaka is the only region where research on women artists is advancing, but in the future, I very much hope that other regions will make similar efforts and that the scope of investigation will expand to examine topics like shared networks between women artists.

Women artists are not classified by school or genre, as is the case for their male contemporaries, and are often uniformly referred to as “accomplished ladies (keishū).” Though this has the advantage of making it easier to distinguish women artists, it leaves one with the impression that they are not treated equally to men.

2

Women who continued to be active long after their marriage include Kyoto’s Shōha Itō (1877–1968), whose husband was a nihonga painter, and Osaka’s Chigusa Kitani (1895–1947), whose husband was a jōruri scholar. S. Uemura had one child but did not marry, electing instead to prioritize her career.

3

Nittenshi (A history of the Japan Fine Arts exhibitions), vols. 1~10, ed. Nittenshi Hensan Iinkai [Commission on the Compilation of the History of the Japan Fine Arts Exhibitions] (Tokyo: Nitten Corporation, 1980–83).

4

Tomoko Ogawa, “Josei Nihongaka o meguru kōsatsu—Santo no naka no Osaka (A consideration of women nihonga artists—Osaka among the three cities),” in the exhibition Ketteiban! Josei gaka-tachi no Osaka (Osaka in the Eyes of Women Artists), pp. 8–15 (Osaka: Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka/ The Sankei Shimbun/ Kansai Television, 2023).

5

Bijinga portraits were popular as collectibles, but they were not suitable for tokonoma display.

6

C. Kitani primarily painted figure paintings of women, but before studying at S. Ikeda’s school, she learned bird-and-flower painting under C. Fukada.

7

The kimono dealer and author, Ban’yō Okada (1873–1946) refers to the ubiquity of ukiyo-e (bijinga) artists in Osaka, stating that, “With Tsunetomi Kitano as forerunner, 606 accomplished female painters have appeared, and what’s more, the total number of artists has reached 2,000.” See Okada Ban’yō, “Keihan gadan zakkan (Miscellaneous impressions of Kyoto and Osaka’s art circles),” Chūō bijutsu (February 1916). Although no basis for this figure is presented, Okada’s account of roughly one-quarter of all the artists in Osaka at that time being women is close to the results for Osaka nihonga works selected for display in the early public exhibitions that are recorded in the Nittenshi. According to my investigation, which is cited in footnote 4, the percentage of artists from Osaka selected for these exhibitions who were women was 22%.

Tomoko Ogawa

Born in Tokyo, Tomoko Ogawa is Senior Curator (Art) and Collection Manager at the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka. She graduated from Kyoto University with degrees in law and literature before departing her doctoral course in art and aesthetics at Kyoto University to complete a Diplôme d’études approfondies (Diploma of Advanced Studies) at Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne University. She began working in the planning office of the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka in 1996. Her research interests include western art history and nihonga (prewar Osaka art circles and women artists). Since the museum’s official opening in 2022, she has curated the Modigliani (2022), Osaka in the Eyes of Women Painters (2023–24) and CLAUDE MONET: Journey to Series Paintings (2024) exhibitions. Her major edited works include Shima Seien to Naniwa no josei gaka (SHIMA Seien and Women Artists of Osaka in the Early 20th Century) (Osaka: Tōhō Shuppan, 2006), while her major publications include “Josei gaka to Osaka: bunjinga kara bijinga made, josei-tachi wa Osaka gadan o yomigaeraseru ka? (Women Artists and Osaka: From Bunjinga to Bijinga, Are Women Artists Reviving Osaka’s Art Circles?),” Bijutsu Forum 21 no. 17 (2008): 66–70; “Kindai Nihonga ni egakareta josei no ‘oi’: josei gaka ga bijinga ni kokoromita ‘toshima-bi’ no hyōgen (‘Aging’ Women in Modern Nihonga: Women Artists’ Attempting to Express the ‘Beauty of Maturity’),” Bijutsu Forum 21 no. 33 (2016): 64–69; “Atomi Kakei: josei kyōiku ni jinryoku shita Osaka yukari no josei gaka (Kakei Atomi: A Woman Artist Born in Osaka who Dedicated Herself to Women’s Education),” Tekijuku no. 51 (2018): 67–76; and “Nihonga to josei sakka (Nihonga and Women Artists),” Bijutsu Forum 21 no. 50 (2024): 28–34.

Tomoko Ogawa, "The Women Nihonga Artists of Osaka." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/peintres-femmes-de-nihonga-a-osaka/. Accessed 12 February 2026