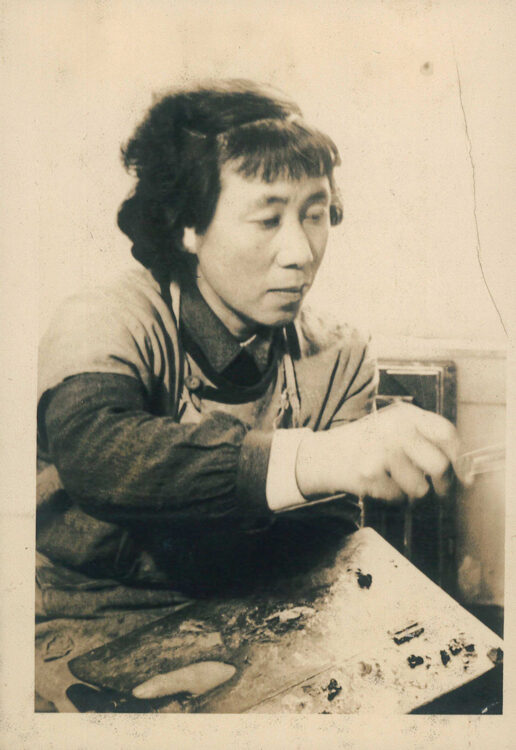

Shōen Uemura

Kojima Kaoru, Josei zō ga utsusu Nippon: Awase kagami no jigazō [Japan as reflected in images of women: Self-portraiture in opposing mirrors], Tokyo, Brücke, 2019

→Reiko Nakamura, “The Rakkan (Signatures) on the Paintings of Uemura Shoen”, Bulletin of The National Museum of Modern Art, no. 16, 2012, pp. 6–29

→Harada Heisaku and Uchiyama Takeo, Shoen Uemura, 2 vol., Kyoto, The Kyoto Shimbun, 1989

Uemura Shoen, Kyoto City Museum of Art, Kyoto, 17 July–12 September 2021

→Uemura Shoen, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, 7 September–17 October 2010 ; The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, 2 November–12 December 2010

→Uemura Shoen: 100th Anniversary of the Artist’s Birth, Kyoto City Museum of Art, Kyoto, 1–23 October 1974

Japanese painter.

Shōen Uemura was one of the leading women artists of modern Japan. In 1948, she became the first woman to be awarded the Bunka Kunshō [Order of Culture]. Additionally, among artists of the modern era, she remains (as of April 2023) the only woman whose works have been designated Juyō Bunkazai [Important Cultural Properties].

The majority of S. Uemura’s works depict the female form. Using ukiyo-e iconography as a reference or mining subject matter from traditional performing arts, such as Noh theatre, she painted what she herself considered to be the “ideal female image”. She began attracting attention as a painter in her late teens, and many women artists subsequently followed her example. Her work also triggered the reemergence of the bijinga (portraits of beautiful women) genre within the art world. Ultimately, however, she was unrivalled in her day for her high degree of technical skill and her ability to portray the inner lives of fully independent and spiritually self-reliant women.

In 1887, S. Uemura enrolled in the Kyoto Prefectural School of Painting (now the Kyoto City University of Arts). The following year, she dropped out and became a student of Shonen Suzuki (1848–1918), who had served as her mentor at the art school. In 1890, she exhibited the painting Shiki bijinzu [Beauties in Four Seasons; whereabouts unknown] at the Third National Industrial Exhibition (Naikoku Kangyō Hakurankai). It was purchased by Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn (Arthur William Patrick Albert, 1850–1942), which attracted a great deal of attention. In an effort to learn more about painting, she began attending the private painting school of Bairei Kōno (1844–1895), a member of the Maruyama-Shijō school of painting, from 1893 and, following B. Kōno’s death in 1895, continued studying under his disciple, Seihō Takeuchi (1864–1942). In 1900, she exhibited the painting Hanazakari [Full Bloom; whereabouts unknown) at the Ninth Japan Painting Association (Nihon Kaiga Kyōkai)/Fourth Japan Art Institute (Nihon Bijutsuin) Joint Painting Exhibition, where she won an award and garnered significant attention in the art world.

In 1907, she exhibited Nagayo [Long Night; collection of the Fukuda Art Museum] at the inaugural Bunten Exhibition (the precursor of the Nitten Exhibition) and continued to exhibit at that show thereafter. At around this time, the art world saw a resurgence of the bijinga genre, with paintings in this style being caught between public popularity and critical censure – that such paintings depict a woman’s form without containing any substance, or that the depictions of these women are vulgar etc. As if in response to this phenomenon, S. Uemura’s work from this period – for example, Hanagatami [Flower Basket, 1915, Shohaku Art Museum collection] and Honō [Flame of Jealousy; 1918 Tokyo National Museum collection] – focuses on the interior lives of the subjects, in direct contrast to her earlier work. Following this, she continued experimenting with various modes of expression, such as in Yang Guifei [1922, Shohaku Museum of Art collection], which emphasises the intricate depiction of individual details.

While these endeavours were underway, S. Uemura’s standing in the art world was steadily improving. In 1924, she joined the committee of the Teiten Exhibition (which succeeded the Bunten in 1919), and the number of commissions that she received from such patrons as the imperial family and various business conglomerates gradually increased.

In 1934, S. Uemura’s mother passed away. Her mother had raised her single-handedly and had been the one to encourage her pursuit of a painting career. Following her mother’s death, S. Uemura’s longing for her late mother came to be visible in her depictions of customs of past, as seen in such works as 1934’s Boshi [Mother and Child; National Museum of Modern Art collection].

The 1930s also marked the period that saw the successive creation of a series of large-scale pieces that could be considered the culmination of her work. These included Jo no mai [Dance Performed in a Noh Play; 1936,Tokyo University of the Arts collection] – a rare example of a work that draws on modern customs for inspiration – and Sōshi arai Komachi [Lady Komachi Washing Away a Poem, 1937, Tokyo University of the Arts collection] – a piece that makes use of her long-term fascination with Noh plays. In the 1940s, during S. Uemura’s later years, she increasingly began producing small-scale works but nevertheless produced many excellent pieces, such as Banshū [Late Autumn, 1943, Osaka Municipal Museum of Art collection], which focuses on the daily lives of the townsmen of a bygone age.

A biography produced as part of the “Women Artists in Japan: 19th – 21st century” programme

© Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions, 2023