Research

Paula Boi-Gony, Re-NéSens, 1998, assembled and painted cut plywood panels, pandanus mat, knotted fabric, felt pen drawing on paper, © ADCK – Centre culturel Tjibaou

The Professionalisation Processes and Emancipatory Strategies of Four Kanak women Artists in New Caledonia

Working in the face of a double form of traditional and colonial patriarchy and in the midst of a turbulent political climate, Paula Boi-Gony (born 1963), Yvette Bouquet (born 1955), Micheline Néporon (born 1955) and Denise Tiavouane (born 1962) are pioneers: they were the first to export their multimedia works abroad and “the group of artists who experienced the fastest developments in the field of contemporary art” in New Caledonia”1 On the initiative of the Djinü Owa association (its name means “spirit of the hut” in the Nyelâyu language), these artists developed their works alongside each other and are seen as inextricably linked by the public while also retaining their own individuality. The start of their careers in the late 1980s coincided with the Kanak cultural renaissance movement, the inception of which was Melanesia 2000 (1975), the country’s first Melanesian arts festival and a major turning point in the four artists’ outlooks, who all agree to the importance of this founding moment. This renaissance can also be traced to the Matignon-Oudinot Agreements (1988), which marked the end of the period known as the “Events”2 and prompted, among other things, the implementation of the OCSTC, the Agence de développement de la culture kanak [the Agency for the Development of Kanak Culture],3 the purpose of which was to encourage contemporary forms of expressing Kanak culture. The training these artists undertook, and the contact with other artists and with motifs from the Pacific and elsewhere, as well as their political commitment and community work, are some of the elements that can help us understand the strategies they used in order to exist as Kanak women artists and the impact they had on the professionalisation of art in New Caledonia.

Micheline Néporon, Tapa, 1999, banyan bark tapa cut, glued and painted, acrylic paint, 152 x 89 cm, © ADCK – Centre culturel Tjibaou

In addition to a political climate that was favourable to the rehabilitation of indigenous culture, which the colonial powers had long suppressed, the careers of these four artists were also jumpstarted once they had access to training. They began attending the Académie de la Peinture in Nouméa in 1982, as well as classes taught by artist Jean-Pierre Le Bars (born 1951) at the OCSTC. Le Bars played a decisive role for three of these artists by introducing them to Oceanian art. In these lessons they discovered – from a European, ironically – the richness of the cultures around them and the potential that their own tradition held. M. Néporon left to study at the École des Beaux-Arts in Bordeaux and then in Marseille from 1990 to 1992. Beyond the theoretical instruction they all received, it was mostly the people they met during local cultural events, such as the seasons held in the lead up to the creation of the Tjibaou Cultural Centre (1995-1998), or international shows, such as Paradise Now? Contemporary Art from the Pacific (2004) in New York, which left a durable impression on them. They were able to draw from these contacts with other cultures and immerse themselves in these exogenous forms, all the while establishing “a new syntax”4 rooted in the tradition that ties them together.

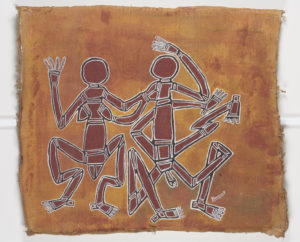

Denise Tiavouane, La Danse, 1994, paint, collage and vegetal fibre on paper, 78.8 x 63.8 cm, © ADCK – Centre culturel Tjibaou

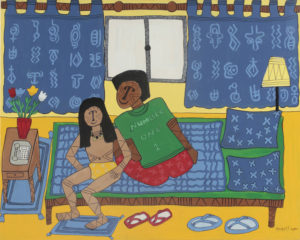

They each started out painting and drawing, mediums that were almost exclusively reserved for women among Melanesian artists at the time, as confirmed by the inaugural exhibition of painters and sculptors Ko I Névâ (which in Ajië means “spirit of the country”) in 1990. The first works they produced were figurative, depicting Caledonian landscapes, local legends and other scenes of daily life. According to Susan Cochrane there were no traditional constraints on painting at the time.5 They found a degree of freedom in these paintings, of which D. Tiavouane has said, “We were allowed to make them because they were just stories, because they didn’t exist”, as opposed to woodcarvers who, on the other hand, were forced to respect tradition.

Yvette Bouquet, L’Hôtel Laetitia, 2006, acrylic on canvas, 80 x 100 cm, © ADCK – Centre culturel Tjibaou

Subsequently, the traditional ancestral technique of engraved bamboo, which was abandoned around 1917 following colonisation and the indigenous people’s forced acquisition of the Western writing system became part of the artists’ practices. P. Boi-Gony discovered the technique during the Fourth Festival of Pacific Arts in 1984 and decided to revive it, vowing that it would one day be taught in schools, and prompting M. Néporon, who had also rediscovered the technique with J.-P. Le Bars, to follow in her footsteps. They carved bamboo with scenes of present-day life, not with the aim of achieving “the artificial resuscitation of relics from the past, but to express contemporary identity issues”.6 Y. Bouquet also uses engraved bamboo motifs in her painting, in addition to those found in petroglyphs, which are omnipresent in her production.

Micheline Néporon, Les Huit Aires linguistiques, 1996, felt pen and varnish on bamboo, 136 x 9 cm, © ADCK – Centre culturel Tjibaou

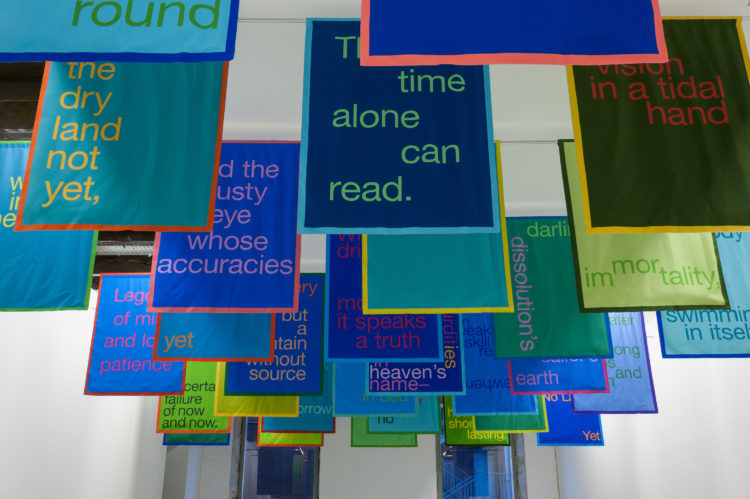

In 1996, bolstered by their many encounters with foreign artists and professionals in the field of culture, they introduced installation into their practice, especially in the case of D. Tiavouane and M. Néporon. Les Taros qui pleurent [The crying taros, 1996] is one example of a site-specific installation, presented by D. Tiavouane at the Second Asia-Pacific Triennial in Brisbane.7 It consisted in taro and yam plantations – tubers that symbolically represent women and men – from which the cries of a baby could be heard, calling out to its forebear, asking, according to the artist: “What is my place?”

Denise Tiavouane, Éléments naturels, 1994, watercolor and collage on paper, 56 x 45 cm, © ADCK – Centre culturel Tjibaou

But above all, what needs to be highlighted is the way in which they responded to the political context: when M. Néporon called for reconciliation in her installation at the third Biennale d’art contemporain de Nouméa (1997), under the direction of Jean-Hubert Martin, she echoed the tensions at play between communities and the future of a country destabilised by the “Events”. The performative installation consisted in various tea-making objects and elements of local daily life arranged on a mat. P. Boi-Gony also evoked politics when she painted Jeu de dupes [Fool’s game] (2008) to mark the occasion of the Matignon-Oudinot Agreements. The four artists also became involved on a more personal level: Y. Bouquet was a member of the GFKEL (Groupe des femmes kanak et exploitées en lutte – Exploited Kanak. Women’s Struggle Group) and P. Boi-Gony took part in the creation of the separatist flag when she worked as an assistant to J.-P. Le Bars at the ADCK. Finally, although political activism is often visible in their work, what constitutes feminist activism for them is the “act of artistic creation itself”8 rather than the subjects they illustrate – at least according to historian Alice Bullard, who underlined the importance of these artists “in the context of the Kanak patriarchy”.9 D. Tiavouane mentioned this traditional framework in an interview, recalling that in the Melanesian world, women are often seated; she therefore equates her ambition with “learning how to stand”.

Paula Boi-Gony, L’Avenir en couleur, 1996, acrylic on canvas, 296 x 139 cm, © ADCK – Centre culturel Tjibaou

In a fight for the recognition of a Melanesian culture that had long been suppressed, they also fought for the professionalisation of artists in New Caledonia. At the start of their careers all four of them regularly partnered with the ADCK, which supported their first solo exhibitions.10 However, the relationship with the institution was at times conflicted: in 1999, P. Boi-Gony felt that the reason the public had often thought that Kanak artists “belonged” to the ADCK was “because they [had] made use of the only tool they could count on”,11 and this tie seems to have been severed nowadays with some of these artists who might have felt they were taken advantage of. S. Cochrane’s response to this question is more nuanced, reminding us of the considerable opportunities they were afforded, which helped them to gradually free themselves from the marginalisation of Kanak artists at the time.

Paula Boi-Gony, Nounou Zak, 2003, acrylic and pastel on paper, 73.4 x 53.3 cm, © ADCK – Centre culturel Tjibaou

In response to what they saw as a lack of institutional support, and as had regularly been the case on the island in terms of women’s struggles, the associative format enabled these visual artists to take action. This was how the association Djinü Owa was created in 1992, which they intended as a means of organising events themselves and facilitating the dissemination of the work of Kanak artists, at a time when there was little representation of their work in galleries. They also contributed to the emergence of the associations SIAPO in 1999 and La Case des artistes in 2012, both with the goal of creating a legal structure for the status of artist on New Caledonia and the implementation intellectual property rights, the absence of which they found regrettable.

Yvette Bouquet, Profil art, 1996, acrylic on canvas, chamfered fixed frame, central crosspiece, 145.5 x 91.5 cm, © ADCK – Centre culturel Tjibaou

It seems important here to emphasise that, alongside their careers, these women often had to work several jobs so they could afford the means they required to pursue an artistic profession, and that they were dependent, like many women artists, on their family situation. Y. Bouquet recalls that she had to live at the home of her father for a long time, and that P. Boi-Gony and D. Tiavouane could rely on the financial support of their husbands. The success they enjoyed seems therefore to be based more on their social status than on any financial recognition, as underlined by D. Tiavouane: “I earn more admiration than cash.”

Yvette Bouquet, L’Homme et la Femme, 1996, acrylic and natural ochres on burlap canvas glued on fixed frame, newspaper glued to the back of the canvas, 99 x 113 cm, © ADCK – Centre culturel Tjibaou

Like many other women artists isolated from the omnipotent West, P. Boi-Gony, Y. Bouquet, M. Néporon and D. Tiavouane were sidelined from a phallocratic and euro-centred art history. As pioneers in New Caledonia, they had their works shown multiple times, but they still remain little-known abroad. Despite this, they have contributed to the professionalisation and broader reach of contemporary Melanesian art in the Pacific and beyond, and have enjoyed an exhaustive historiography and local recognition. Several of their works were acquired by the Fonds d’art contemporain kanak (FACKO), which was established in 1995.12 Far from having simply followed Western aesthetic trends, they made use of the styles and techniques to which they were exposed to create new forms, emancipating themselves from the limitations of traditional artwork and giving free rein to an imagination nurtured by narratives of the past and more recent encounters. It is therefore imperative that we take further interest not only in the work of P. Boi-Gony, Y. Bouquet, M. Néporon and D. Tiavouane works, but also those of the women who followed in their footsteps, so that they can at last earn the visibility they deserve beyond the place they are from.13

Susan Cochrane, “Art contemporain kanak : une expression en expansion”, in Le Mémorial calédonien, vol. 10, ed. Philippe Godard (Nouméa: Pacifique Presse, 1998), p. 363.

2

The “Events” refer to a near-civil war that took place between 1984 and 1988, which ended with the signing of the Matignon-Oudinot Agreements on 26 June 1988, followed by the Nouméa Accord on 5 May 1998.

3

The Office culturel scientifique et technique canaque (OCSTC), founded in 1982, was replaced in 1986 by the OCC, the Office calédonien des cultures [Caledonian cultures office] and in 1989 by the ADCK, the Agency for the Development of Kanak Culture, the main instrument of which is the Tjibaou Cultural Centre.

4

Lydie Gardet, “Cartographie”, Brwâdjï : Micheline Néporon, Denise Tiavouane, Yvette Bouquet, Paula Boi Gony (exh. cat. Païta: Mairie de Païta), p. 9.

5

The comments were made during interviews conducted between June and December 2021, excerpts of which can be found in the research file that comes with this article and is available at the AWARE documentation centre. Australian curator Susan Cochrane was head of the Kanak and Pacific contemporary arts section at the ADCK in the late 1990s.

6

Roberta Colombo Dougoud, “Kanak Engraved Bamboos: Stories of the Past, Stories of the Present”, in Tides of Innovation in Oceania: Value, Materiality and Place, eds Elisabetta Gnecchi-Ruscone and Anna Paini (Canberra: ANU Press, 2017), p. 126.

7

See Emmanuel Kasarherou, “Denise Tiavouane”, The Second Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery, 1996), p. 123.

8

Alice Bullard, “Le théâtre des plages en Nouvelle-Calédonie: présentation du corps et art kanak féministe”, Journal de la Société des océanistes(1999): p. 137.

9

Ibid.

10

P. Boi-Gony, M. Néporon and D. Tiavouane would even work for the OCSTC and later the ADCK.

11

Filippi Orso, ed., Chroniques du pays kanak, vol. 3 (Nouméa: Planète Mémo, 1999), p. 222.

12

The FACKO owns 17 works by P. Boi-Gony, 11 by Y. Bouquet, 31 by M. Néporon and 8 by D. Tiavouane.

13

In reference to M. Néporon’s exhibition Le lieu d’où je suis, which translates as “the place where I’m from”, hosted by ADCK in 1993.

14

En référence à M. Néporon, Geïra. Le lieu d’où je suis, cat. exp., ADCK, 1993.

Sarah Lolley, "Pioneers: Paula Boi-Gony, Yvette Bouquet, Micheline Néporon and Denise Tiavouane." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/pionnieres-paula-boi-gony-yvette-bouquet-micheline-neporon-denise-tiavouane-processus-de-professionnalisation-et-strategies-emancipatrices-de-quatre-artistes-femmes-kanak-en-nouvelle-caledonie/. Accessed 14 February 2026