Interviews

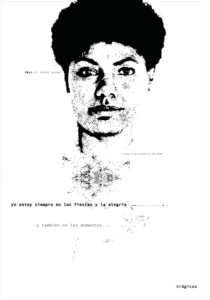

Natalia Iguiñiz, Buscando a María Elena [Looking for Maria Elena], 2011–2012, street action © Courtesy Natalia Iguñiz

This interview explores Natalia Iguiñiz’s feminist practices.1 Perrahabl@ (1999), her first street action, carried out as a member of LaPerrera,2 involved the city-wide distribution of 3,000 posters with an image of a female dog and normalised popular slang linking women, sexuality and animality.3 This piece provoked a national debate. Her subsequent street works Buscando a María Elena [Looking for Maria Elena, 2011-2012] and Dejo este cuerpo aquí [I leave this body here, 2020] contained more autobiographical elements. This interview concludes with a presentation of her latest project, working with the collective Retablos para la Memoria [Altarpieces for memory, 2022–2023].

Colectivo LaPerrera, Perrahabl@, 1999, street action © Courtesy Natalia Iguñiz

Colectivo LaPerrera, Perrahabl@, 1999, poster © Courtesy Natalia Iguñiz

María Laura Rosa: In your work there is a remarkable fluidity in the passage between your street actions and your pieces meant to be shown in the context of traditional art circuits. Is there some specific approach that facilitates this transition?

Natalia Iguiñiz: Perrahabl@, María Elena and Dejo este cuerpo aquí are traversed by very specific biographical elements embedded in social relations, which is how they produce a dialogue between exhibition spaces and the street. For me, the two poles of the back-and-forth process you mentioned are complementary. Working in the street produces an enormous energy because instead of the usual suspects you’re working with people outside of your circle of friends, professional colleagues and family, and big cities like Lima are especially fragmented in social, economic and cultural terms.

Taking to the streets, whether as part of a group or by yourself, makes it possible to establish a bridge between the exhibition space and the city, giving you a chance to see what’s happening and experience the reactions and thinking of people excluded from contemporary art circuits. It’s very invigorating. For me it’s important to meet others who make me feel like a part of this community and keep me from being dragged down by the highly unequal and unjust social structure we live in.

Perrahabl@ was situated at the end of the Fujimori dictatorship, at the end of the 1990s. In that period, feminists who arose in the 1970s became more centred on institutions and abandoned the streets. With Perrahabl@ we put forward a bit of a return to our early days through processes outside of the dictatorship’s ambit, since the Fujimori regime had taken over the media. Overnight the streets were postered with a decidedly non-commercial message. The slogans were not the kind associated with more institutional feminism, like “Stop gender violence”, which lack impact because they don’t really grab people. At a time when there was little public space for irony, LaPerrera used male supremacist phrases in an ironic fashion, with no further explanation. We intervened in a circuit to take advantage of its potential for our political project – interrogating patterns of sexual violence. Through Perrahabl@ I began to work for feminist NGOs, and we launched campaigns with more direct goals. It was an important moment, because I hooked up with the Sindicato de Trabajadoras del Hogar [the Household Workers’ Union]. I did campaigns with them, linking the work I had been doing with feminist and trade union issues.

Natalia Iguiñiz, Buscando a María Elena [Looking for Maria Elena], 2011–2012, poster © Courtesy Natalia Iguñiz

Natalia Iguiñiz, Buscando a María Elena [Looking for Maria Elena], 2011–2012, poster © Courtesy Natalia Iguñiz

Natalia Iguiñiz, Buscando a María Elena [Looking for Maria Elena], 2011–2012, street action © Courtesy Natalia Iguñiz

Natalia Iguiñiz, Buscando a María Elena [Looking for Maria Elena], 2011–2012, poster © Courtesy Natalia Iguñiz

MLR: What was the context for Buscando a María Elena?

NI: More than a decade later, in 2011–2012, when I made Buscando a María Elena, the context in Peru was different. Earlier since the mid-1980s Lima had been wracked with the highest inflation ever. The 1990s brought the disastrous neoliberal policies of the Fujimori government. Amid the devastating armed conflict in the 1980s and 1990s, the city fell apart. María Elena Moyano (Lima, 1958–1994) was an Afro-Peruvian activist, a feminist leader of the left, whom I knew when I was a child. She was assassinated because she stood up to the terrorist Shining Path group. Her body was dynamited, blown to pieces. According to the Peruvian myth of the Inkarri, when the Spanish conquerors killed the last Inca leader they cut his body into pieces and sent each of his arms and legs to a different corner of the Tahuantinsuyu, the Inca empire. One of his extremities was sent to each of the suyus (regions), and his head went to Cuzco. According to the myth, the unjust order that was imposed will be overturned when his body becomes whole again. This can also be interpreted as the possibility of the people taking action for the sake of a better life. I feel that the figure of María Elena, an opponent of the Shining Path who was blown to pieces because her struggle was for the cause of life and for an end to the violence, represents an enormous source of strength, an untapped potential, not only in terms of women’s access to power, but also because she embodied a different kind of leadership. When I made the piece, the right was wielding the spectre of the armed struggle and trying to directly link the left with terrorism. They constantly attacked the first woman elected mayor of Lima. For me, this piece was a way to continue the debate about how we women can come to power as advocates of feminism and the demands of the left. My piece tries to go beyond the celebrity status that has been built up around her and to address her as a person, with all her contradictions and complexity.

The piece consists of posters with graphics representing the different parts of María Elena’s body. The plan was to bring them together on the anniversary of her death. But when that day came, I decided not to bring the posters together because the goal of a political power giving space to pleasure and sexuality had not yet been achieved. For women, the exercise of political power is an unfulfilled project.

There was an aesthetic shift between Perrahabl@ and Buscando a María Elena. The former appropriates the “chicha”4 aesthetics used in advertising, with primitive drawings and fluorescent colours. The piece’s high contrast iridescent colours are combined with the more 1970s psychedelic look adopted by Peruvian cumbia (“chicha”) bands of that time. Yet when I started to work on the body of María Elena, which in a way is my own body, I didn’t need colour. Furthermore, I had been able to read things that she wrote and her media interviews. I took excerpts from them and put them on the posters. They are monochromes, black and white. Instead of an image of a dog, there is a corpse.

The intense process of bringing up my children led me to invent new ways of continuing to make art. Struggling intensely and on my own to keep my household together and support my children led me to work more at home. Between 2012 and 2016 my production was limited to whatever was possible for me at that time, trying to politicise domestic life, mainly through photography. In 2016, with the #Ni Una Menos [#Not one woman less] movement that had emerged in Argentina, I started to hit the streets again.

Natalia Iguiñiz, Dejo este cuerpo aquí [I leave this body here], 2020, cardboard signs © Courtesy Natalia Iguñiz

MLR: How did the context of the massive upsurge of feminism starting in 2015 impact your piece Dejo este cuerpo aquí?

NI: In 2016 I began to take courses in art and feminism and joined women’s groups. But the statistics regarding sexual violence remined unchanged. I began to feel that none of this made any difference. We would march and hold sit-ins but the violence continued. Actually, it became worse. Younger and younger girls were being raped, even babies. A girl was burned alive in a bus. Dejo este cuerpo aquí was not an exposure. It was a desperate action. I remember how when I was a child, people used to put up cardboard boxes on lamp posts with signs asking for contributions of medicine. Some were put up in the middle of avenues where nobody could read them. To me, that seemed very desperate. I had collected photos documenting the various uses of such boxes, whether in marches, as posters or appeals for help, for alms and food. Furthermore, when the common graves left behind by the armed conflict are dug up, the remains of the dead are turned over to the families in cardboard boxes. I began to gather these materials as a way of looking at the status of this issue, and the state of art. I was working with cardboard boxes with the understanding that people use them not only as a means of self-expression, but also as a temporary shelter and a way to ask for help and demand what they need.

In the middle of all this the COVID pandemic hit. I found myself locked up in my house with my two children. Our delivery boxes began to pile up. I began to think about how a body needs rest. The image of a recumbent body arose in my mind. The pandemic mainly affected women, those doing renumerated jobs and unpaid domestic work as well, with no networks or other help. Many women were locked down with their aggressors. One way of getting the body out on the streets was by putting up posters in the least expected places. The text was printed in very small type to alter your movements as you approached it. You had to bend over to see what was happening with this person. This was very different from the usual way posters are used. The strategy was not to raise a hue and cry but to pose the question of how to resist, how to exist, when you can’t go out. This piece was a response to a situation where people had to withdraw, when we needed new strategies to confront the violence used against us, then and now.

Colectiva Retablos por la Memoria, First intervention with one hundred retablos for democracy, December 2022, carried out in Barranco with the participation of several Peruvian artists © Courtesy Natalia Iguñiz

Colectiva Retablos por la Memoria, First intervention with one hundred retablos for democracy, December 2022, carried out in Barranco with the participation of several Peruvian artists © Courtesy Natalia Iguñiz

MLR: I’d like to know more about the current project you launched at the end of 2022 with the Retablos por la Memoria group.

NI: The Retablos por la Memoria collective arose during the protests that broke out after Pedro Castillo’s attempted coup and the subsequent establishment of a new government by Dina Boluarte. Gala Berger contacted Venuca Evanán and myself with the idea of trying to reach out to people disconnected from the crisis shaking the country. Our objective is to celebrate the lives of the people who have been murdered, and to emphasise the importance of preventing the institutionalisation of violence and repression as means of resolving conflicts. Venuca suggested that this memorial take the form of a retablo, a folk altarpiece that resembles a little protective house. We want every single person in Peru to feel that their life has value and should be protected. We can’t allow a single life to be stolen just because someone raised their voice to demand their rights as citizens. We began with a retablo responding to the massacre in Ayacucho; we carried it through the streets of Miraflores (Lima) in response to a call put out by a network of artists for democracy, which includes diverse cultural actions in different regions and Lima neighbourhoods. Then we widened the retablo to include the victims of the massacre in Puno, which we presented during the big march that took place on 12 January 2023. Because of the strong welcome we received then, we decided to work with poster/retablos and carry tens of them in the following demonstrations already being organised. Finally, we carried all of these posters during the massive march of 9 February in the Plaza 2 de Mayo to commemorate the massacre in Juliaca. Now we’re giving workshops to teach people how to make these retablos, and this is expanding to other Latin American countries.

A short version of this interview, conducted between January and October 2023, was posted in Spanish on the DISIDENTA website.

2

A group active in Lima between 1999 and 2004.

3

In Peru, the term “perra” (female dog or bitch) is used to describe women who make free use of their body, thus transgressing social and religious norms. A “perrera” is an animal shelter (translator’s note).

4

Peruvian kitsch aesthetic characteristic of the 1980’s (translator’s note).

5

Le texte original féminise le genre du substantif « collectif » ; nous en faisons de même, à l’instar de certains groupes militants féministes en France qui féminisent également « la collective ». (NdT)

Natalia Iguiñiz (Lima, 1973) is a visual artist, university teacher, mother and feminist activist. She has challenged the patriarchy throughout her 30-year career, in individual pieces produced in the context of the existing art circuits and in street activism, in both cases fluidly blending the specific codes of the two kinds of spaces. Her critical and disruptive projects have made her one of the leading figures in Peruvian and Latin American art and feminist activism.

María Laura Rosa is a professor in the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters of the University of Buenos Aires and a researcher at the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET). Her scholarship focuses on feminist art in Argentina, Brazil and Mexico since the 1970s. She coedited O sexo da Arte. Teorías e críticas feministas (2023) with Luana Saturnino, and is the author of De cuerpo entero. Debates feministas y ámbito cultural en Argentina 1960–1980 (2021), as well as many books and articles on feminist art. Her curatorial projects include the exhibitions Querida Felka. Alberto Greco por Ilse Fusková, at Galería W in Buenos Aires (2023) and 40 años de Polvo de gallina Negra. Arte feminista en México at the Museo Cabañas, Guadalajara, Mexico (2023).

An article produced as part of the TEAM international academic network: Teaching, E-learning, Agency and Mentoring.

María Laura Rosa & Natalia Iguiñiz , "“For women, the exercise of political power is an unfulfilled project”: Natalia Iguiñiz and feminist activism in Peru." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/pour-les-femmes-lexercice-du-pouvoir-est-une-puissance-en-attente-natalia-iguiniz-et-lactivisme-feministe-au-perou/. Accessed 10 February 2026