Research

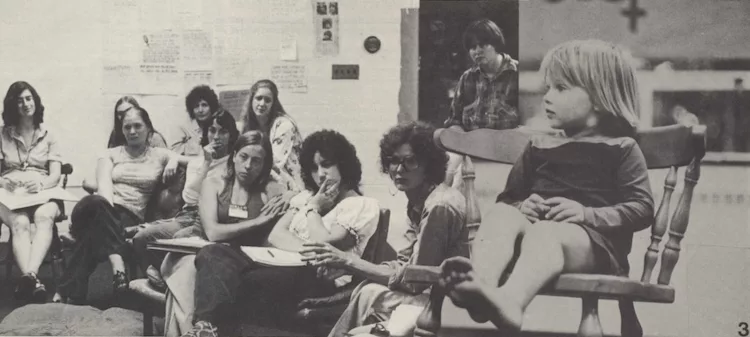

Dita Roque-Gourary and Odette Filippone at the exhibition Les femmes architectes exposent in Koekelberg, 1981 © Archives d’Architecture de l’ULB – the exhibition panel on the right is that of Claire Henrotin

Belgian women’s late arrival in architecture

Belgium has been slower than other Western nations in integrating women into the profession of architecture. It was not until 1926 that the Société Centrale d’Architecture de Belgique (SCAB) gained its first woman member, Jeanne Van Celst (1889–1983), and it was only in 1930 that Claire Henrotin (1908–1989) became the first Belgian woman to complete architecture studies, training at the recently founded Institut Supérieur des Arts Décoratifs de La Cambre in Brussels. Belgium was thus nearly fifty years behind countries like France and the United States. An article published in SCAB’s bulletin in the late nineteenth century reveals the mindset of the time: “If what they say is true, that there are too many architects, real or otherwise, in Belgium, then the situation must be quite different in America or France. There seems to be a shortage of architects in the New World, according to the article below, which we have clipped from a daily newspaper: ‘Women have managed to break down the doors of the medical school; now they are launching an assault on the school of fine arts’.”1

In the first half of the twentieth century, very few women studied or practised architecture in Belgium. La Cambre stands out amongst other schools with its record of ten women graduating between 1930 and 1950. Some, such as Simone Guillissen-Hoa (1916–1996) and Odette Filippone (1927–2002), went on to have significant and even critically acclaimed careers. However, most remained unknown in the architectural community, despite having careers lasting several decades in some cases. As few of their archives have been preserved and their projects were never almost published in the media, researching them is extremely difficult.

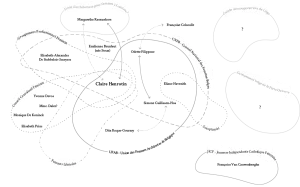

Mapping the feminine and feminist networks of the first generation of Belgian female architects © Elisabeth Gérard

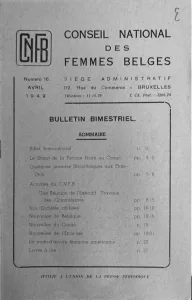

Bimonthly bulletin of the National Council of Belgian Women© CARHIF

Women’s and feminist organisations in Belgium

If we examine the biographies of this first generation of women architects, we notice a consistent engagement, to different degrees, with women’s and feminist organisations. Amongst the fifteen or so female practitioners from the first half of the twentieth century identified to date, no fewer than nine were linked to one or more women’s networks. While these groups were oriented around political leanings (Socialism, liberalism or Christian movements, for example), their commitment to women’s causes remained constant. They frequently invited architects to contribute articles, deliver lectures or display some of their projects at women’s exhibitions.

In 1934, for instance, C. Henrotin was invited to speak as an architect and industry expert in a lecture series on household economics organised by the Fédération Nationale des Femmes Libérales. In the following year, the Groupement Professionnel Féminin, the Belgian section of the International Federation of Business and Professional Women, put on a women’s crafts exhibition in Brussels. The event received positive media coverage: “Yet in our country, two women architects revealed their abilities. These are Madame De Stobbeleir-Smeyers, best known for a tenement building project in Vilvorde, and Madame Claire Henrotin, who developed ingenious plans for a children’s home. Furniture concepts, marketing posters and illustrations of all kinds prove that women excel at many forms of artistic expression.”2

Even more conservative organisations called upon the expertise of women architects. Such was the case with Jeunesse Indépendante Catholique Féminine, which in 1953 asked Françoise Van Cauwenberghe (1922–2020) to contribute an article about the essential role of housing to its monthly publication, Jeunesse et Vie.

Within this constellation of women’s organisations, one stood out for its ties with architects: the Conseil National des Femmes Belges (CNFB), the Belgian branch of the International Council of Women, which had been founded in the United States in 1888 and is still active today. This vast institutionalised organisation was created to unite the country’s various women’s organisations, serving as this era’s ‘essential hub of Belgian feminism’.3 C. Henrotin began playing an active role in CNFB during the interwar period. She joined in 1937 and chaired its Housing Commission from 1939 to 1956. This body included specialists in architecture and construction, as well as scientists, legal experts, sociologists and representatives of other professions. After the war, the Housing Commission expanded to include at least ten members, amongst whom architects represented a significant number. The names S. Guillissen-Hoa, O. Filippone and Eliane Havenith (1918–2004) thus appear repeatedly in the minutes of the organisation’s meetings between 1948 and 1966. The Housing Commission tackled a wide range of issues, many of them closely aligned with contemporary feminist concerns, including the under-representation of women in the field of architecture, the need for communal services in housing developments aimed at supporting women and children and strategies for involving women in urban planning and decision-making.

UIFA Congress, undated, © Archives d’Architecture de l’ULB – Dita Roque-Gourary est au centre de la photo

Union des Femmes Architectes de Belgique

A significant share of Belgium’s first women architects were active in women’s organisations, reflecting a genuine awareness of and sensitivity to women’s issues in the twentieth century, years before the second wave of Western feminism. It is thus unsurprising that these same figures played a role in creating the Union des Femmes Architectes de Belgique (UFAB) in the late 1970s.

Founded and later chaired by Dita Roque-Gourary (1915–2010), UFAB is the Belgian branch of the International Union of Women Architects (UIFA), established in 1963 by Frenchwoman Solange d’Herbez de La Tour (1924), who also served as its first chairwoman. The Belgian organisation was created following the 1978 exhibition Les Femmes Architectes Exposent organised by UIFA at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. Eight Belgian women, including D. Roque-Gourary and E. Havenith, were represented. D. Roque-Gourary then brought a group of Belgian women architects together to form a Belgian delegation at UIFA’s Fifth International Congress in Seattle and Washington, DC, in 1979. In that year, twenty-six women became UFAB members – a number representing roughly ten percent of all women registered with the Ordre des Architectes at the time. Amongst them were C. Henrotin, S. Guillissen-Hoa and O. Filippone, whose careers were already well established or complete.

Lessons to be learned

These archival findings support the researcher’s initial intuition: the first generation of women architects in Belgium were indeed individuals who challenged the gender norms of their time. They pursued a profession traditionally dominated by men and, in some cases, maintained a presence in it for many decades. Focusing on their feminist sensibilities and engagement in women’s networks reveals the important strategy of solidarity amongst women. These architects knew and associated with each other, coming together to discuss architecture outside the conventional, male-dominated professional sphere. They formulated feminist demands, some architectural and others related to their working conditions.

It is now difficult to determine with full certainty whether involvement in women’s networks is specific to Belgian architects or is a reality shared by those in other countries. But what these observations teach us is that research on women architects must always go beyond the archives and other traditional forms of architectural documentation. Very few women architects have archival collections in their own names, and they frequently experienced a degree of marginalisation both during and after their careers. It is therefore enlightening to explore other kinds of historical sources, some quite unexpected, like the archives of feminist organisations or illustrated publications aimed at women.

In Belgium, the archives of the Conseil National des Femmes Belges, kept at the Centre d’Archives d’Histoire des Femmes in Brussels and the Mundaneum in Mons, along with UFAB’s collections in the architecture archives of the Université Libre de Bruxelles, have proved crucial in reconstructing the biographies of several architects, especially C. Henrotin, whose personal archives are lost. Using articles from women’s and feminist journals, personal correspondence, photos and meeting records, we have traced a substantial portion of her career, which diverged from the conventional paths of the era. The most revealing example is undoubtedly a photograph found in UFAB’s archives. Taken during a Brussels exhibition devoted to women architects, it allowed us to credit C. Henrotin with the design of a house in the Belgian Ardennes, thus bringing to light a previously unseen facet of her long and compelling career in rural architecture. This is a striking example of feminist research methodology, in which the archives of women’s organisations and fellow women architects pave the way for new, more inclusive narratives in architecture.

“Des femmes-architectes”, L’Émulation 9/5, 1884, p. 4.

2

“Une exposition d’artisanat féminin”, La Nouvelle Belgique, 25 August 1935, p. 8.

3

Catherine Jacques, “Le féminisme en Belgique de la fin du 19e siècle aux années 1970”, Courrier hebdomadaire du CRISP, 2009/7-8, no. 2012–2013, pp. 5–54.

Architect Élisabeth Gérard graduated in 2022 from the La Cambre-Horta School of Architecture at the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB). She devoted her Master’s thesis to the first women architects who had studied at La Cambre-Horta (Brussels, 1927–1950). This project earned her the La Cambre-Horta thesis prize as well as the first prize for a feminist thesis of the Université des Femmes. She currently practices architecture in Brussels, continues her research at the laboratory Hortence and works as a teaching assistant at ULB.

Élisabeth GérardÉlisabeth Gérard, "Twentieth-century Belgian networks and associations for women architects." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/reseaux-et-associations-darchitectes-femmes-en-belgique-au-xxe-siecle/. Accessed 12 March 2026