Research

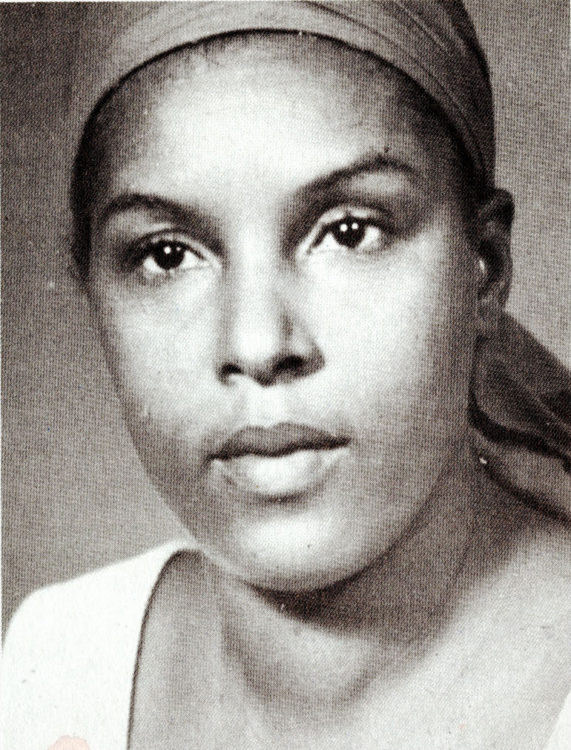

Standing up, surrounded by immense carob trees and swirls of earth, speaking up in front of a circle of women looking at me attentively, with a distrust in their eyes that gradually turned into hope. That’s how I met Claudia Alarcón and some of the women who today make up the Silät collective.

In late 2015 I began to work with women weavers of the Wichi people. I was the coordinator for training programmes organised by Argentine state institutions.1 These workshops were meant to ‘add value’ to the handicrafts made by women of an indigenous community, a territory that, paradoxically, was in conflict with that same state. The idea was to generate ‘innovations’ in counterpoint with a process of questioning and consultations about what to change and why.

A fabric can be transformed according to its use and presentation, but in and of itself it’s already an interrogation and a demonstration of what can be done by something that refuses to disappear.

Chaguar collection process, 2018. © Andrei Fernandez

Chaguar, 2018. © Andrei Fernandez

Chaguar, 2019. © Andrei Fernandez

Claudia Alarcón processing chaguar fibres for weaving, Santa Victoria Este, Salta, Argentina, 2023, Courtesy of Andrei Fernández and Cecilia Brunson Projects

Sending out a search party

In the three years after I began working in the part of the Gran Chaco situated in the province of Salta, Claudia Alarcón attended all of the workshops. I only got to know her voice two years after seeing her in the weekly meetings where increasing numbers of women were connecting as they brought their fabrics to try out new finishings and mixes, and, for the first time, to decide their prices themselves. Until then sales prices had been fixed by others. Men.

The other workshop participants and I quickly understood that the most urgent ‘innovation’ needed to safeguard the community was to get organised. So, although not yet completely conscious of what we were doing, we founded a women’s organisation. Together we began to look for a new outlet for the woven bags that people in the Gran Chaco had always made to carry messages and memories, and which had become one of the few ways they could earn an income.

Claudia was one of the first who dared to make a trip to the cities to sell the nascent group’s products. As the workshops turned into meetings and assemblies, between 2017 and 2021, we took part in circular economy, design and handicraft fairs as part of our search for people who would valorise the work that the Wichi people had refused, and are still refusing, to abandon. In those early years the group called itself Thañí/Viene del monte [Comes from the bush]. It broke up in 2023, and some of its leaders, including Claudia, founded Silät.2

A continuity

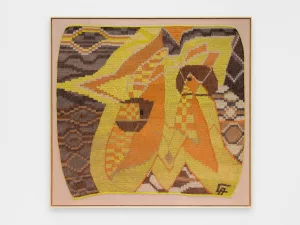

In the Wichi language, the act of weaving can only be described as a continuing action: tayhin (weaving) is an intransitive verb that can also refer to building, reconstructing and healing. Demóstenes Toribio3 points out that when Wichi women weave images together, they are building, reconstructing and healing memories and imaginations as part of a long-term continuum. The territory is also continuously woven on the surface over which it extends, healing its vital transformations and thus producing its texture. The soil, like a skin, conditions the shapes of the monte4 and their fleece. In the woven body, the woven territory, the woven bag, the weaving is the message in which thicknesses are condensed.

They weave – reconstruct – heal images meant to be carried on the body as bags called yicas5 in the Gran Chaco region of Argentina. The geometric shapes of the yicas are named as if they were fragments of living beings, animals and plants. They have a symbolic value superimposed on their practical use that freights them with meanings linked to various dimensions of community life. They are containers specifically used for gathering food, and, since the mid twentieth century, as a kind of currency to buy foodstuffs no longer found in the monte due to the deforestation resulting from agribusiness and other extractive industries.

Chaguar thread, 2018. © Andrei Fernandez

Weaving process, 2021. © Andrei Fernandez

Textiles by Silät, 2023 © Clara Johnston

Chaguar thread and the stars

Thread from the plant known as chaguar has always been of fundamental importance to Wichi women. They live with this plant, which is part of the monte just like them. They tell stories about how this plant never ceases to surprise them because of the shapes it can take and all it can do. It is their teacher and support. Wichi memory recounts that women originally came from the sky and descended on a chaguar thread. Before they were women, they were stars. Now, when they weave, they caress that radiance that was taken from them, while the chaguar transmits messages through its fragrance. The weaver and researcher María del Carmen Toribio says that chaguar fibre is capable of enormous transformations. It can adapt to all kinds of changes and thus teaches Wichi women about their own potential versatility.6

To work with chaguar you have to go deep into the monte to find these plants. This bromeliad grows in the chiaroscuro under the tree cover. You have to be very careful in cutting it so that the thorns around its leaves don’t rip your hands. A spear improvised from a tree branch and a machete are used to gather the leaves, which are then peeled and crushed to loosen the fibres. After being soaked and dried, they are spun onto the weaver’s body. A thigh is used so that a hand smeared with ashes can twist the fibre while the other hand holds the resulting thread.

The thread is dyed with roots, bark, leaves and seeds – the colours of the monte. Artificial dyes can be used to imbue the fibres with bright, sometimes phosphorescent colours. Afterward they are stretched between two brackets, perhaps poles thrust into the ground. The distance between them depends on the size of the future fabric, created hanging in the air using a needle or thorn. The most important element is the movement of the hands – light, choreographed and constant – using the thread to draw eyes, the name given to the holes in the weave that allow the fabric to expand. They are eyes that can open.

The collective imagination

The Wichi people are organised into numerous communities in the provinces of Salta, Chaco and Formosa in northern Argentina. In Santa Victoria Este, a municipality bordering Bolivia and Paraguay, there are more than a hundred Wichi communities. Each exercises its own authority and in turn belongs to the Lhaka Honhat organisation, coordinated by a young woman, Cristina Pérez. Lhaka Honhat has ardently defended its territory for decades, winning its legal recognition as the collective property of five peoples who existed before the establishment of the Argentine state.7 Property held in common means shared ownership of a territory. Although it is organised and divided into subunits for its use, everything belongs to its inhabitants – and not just the human ones.

For these people, images are also a communal territory from which springs a collective imagination. The woven images are jointly-owned property, although each weaving is a particular manifestation to be completed through its use. The person who makes a fabric can sell or exchange it for whatever they need, but the shapes and messages are not theirs alone. Ownership can be transitory and authorship fluid, in line with the Wichí people’s understanding that the same body can be inhabited by different beings.

A weaver can generate an interruption, a change in the continuity in which her work is inscribed, but this modification can be repeated by another member of her community without any conflicts about copying or appropriation. But what happens when the change produces a new, additional value?

Exhibition view, La Escucha y los Vientos. Narratives and Inscriptions of the Gran Chaco, October 2020–January 2021, ifa-Galerie de Berlin, 2020. © Victoria Tomaschko

Claudia Alarcón & Silät, Okajhiaj [A landscape of happiness], 2024, hand-spun chaguar fibre, woven in yica stitch, Photography by Silvia Ros, courtesy of the artists and Cecilia Brunson Projects

Exhibition view, Claudia Alarcón & Silät | Nitsäyphä: Wichí Stories, Cecilia Brunson Projects, London, October 2023, Photography by Eva Herzog, courtesy of the artists and Cecilia Brunson Projects

Claudia Alarcón, Kates tsinhay [Star women], 2023, hand-spun chaguar fibre, woven in yica stitch, Photography by Eva Herzog, courtesy of the artist and Cecilia Brunson Projects

Exhibition view, La vida que explota, MALBA-Puertos, 2024, Photography by Santiago Orti & Diego Spivacow, courtesy of MALBA-Puertos and Cecilia Brunson Projects

Exhibition view, La vida que explota, MALBA-Puertos, 2024, Photography by Santiago Orti & Diego Spivacow, courtesy of MALBA-Puertos and Cecilia Brunson Projects

Exhibition view, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere, 60th International Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, 2024, Photography by Marco Zorzanello, courtesy of la Biennale di Venezia and Cecilia Brunson Projects

Exhibition view, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere, 60th International Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, 2024, Photography by Marco Zorzanello, courtesy of la Biennale di Venezia and Cecilia Brunson Projects

A silät

The term silät, meaning message, was the name given to the first pieces made for contemplation that the Thañí weavers made for the 2020 exhibition La escucha y los vientos8 that I curated in the Berlin ifa-Galerie as an experiment in collaborative creation.9 With the help of the Salta artist Yannitto Guido (born 1981), the Thañí weavers worked in subgroups with different materials and made bigger pieces, on a scale that makes them look like banners, or as if the weavings were an outcry.

When I asked Claudia what words could describe these collectively-made fabrics, she told me the group agreed that they should be called silät, because they are a message meant for people who don’t know that Wichi women continue to weave just as their ancestors did.

After participating in contemporary art fairs where this work was presented in 2020, in the following year Claudia was invited to show her work at the Cecilia Brunson Projects gallery in London. She insisted that this be done along with work by the Silät weavers. We called the show Nitsäyphä,10 a Wichi word for the explosion when spring water first begins to flow, and their own power as well. The opening of a space to see and realise one’s own destiny.

This was part of the Proyecto Bosques Nativos y Comunidad in conjunction with the technical team of the INTA (Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria de Argentina) of the Agencia de Extensión Rural de Santa Victoria Este, Salta, Argentina.

2

In July 2024 this group brought together 120 women of different generations who worked as an association to make pieces to be sold on the art market and distributed as utilitarian textile handicraft objects through various commercial outlets.

3

The Wichí people’s communicator. He is a member of the Consejo de la Lengua Wichí Lhämtes and a bilingual (Wichi-Spanish) translator for Acceso a la Justicia. He works as an interpreter during the interviews and testimonials given by the women of the Silät collective and the spiritual teacher Caístulo.

4

The “monte” (bush) is an Argentine ecoregion mainly marked by the predominance of shrubbery, located at the foot of the Andes mountains in the northeast, central and northern provinces of Patagonia. The Wichí say that they live in and with the monte, in the Gran Chaco. In Argentina the word monte has acquired a political dimension related to the defence of this territory in the face of advancing agribusiness, and because it was the theatre of revolutionary rural guerrilla warfare in mid-twentieth century northern Argentina.

5

Yica is a word in the Quechua language. It is used in the Salta region of the Chaco when speaking in Spanish about a kind of square-shaped bag used by local people as part of their everyday outfits, worn at the hip with the strap crossed over the chest like a backpack.

6

In a lecture given as part of the Jornada de Arte Textil held at the MALBA (Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires), February 2024.

7

Since the early 1980s they have asked for a single ownership title, with no subdivisions, in the name of all the indigenous communities that inhabit what used to be called the Lotes Fiscales 55 y 14 del Departamento Rivadavia, in the province of Salta. Since the Argentine state failed to reply, in 1998 the Asociación Lhaka Honhat, under the sponsorship of the CELS, filed a complaint with the Inter-American Human Rights Commission. In 2012, the Commission issued a report on the merits of the case declaring that the communities’ rights had been violated and ordering the payment of reparations. Because of the State’s non-compliance, in 2018 the case was submitted to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. “The Court determined that the State violated the right to community property. In addition, it determined that the State violated the rights to cultural identity, a healthy environment, and adequate food and water, due to the ineffectiveness of State measures to stop activities that were harmful to them.” https://www.cels.org.ar/web/2020/04/la-corte-interamericana-de-derechos-humanos-condeno-al-estado-argentino-y-fallo-a-favor-de-las-comunidades-indigenas-saltenas/

8

See https://untietotie.org/en/event/the-listening-and-the-winds/

9

I worked as a curator from 2012–17, when I took a break from this practice to immerse myself in the monte, where I coordinated social economy workshops. I took it up again in 2019 to work with the Argentine artist Gabriel Chaile.

10

See https://www.ceciliabrunsonprojects.com/artists/151-claudia-alarcon-%26-silat/

11

Voir https://www.ceciliabrunsonprojects.com/artists/151-claudia-alarcon-%26-silat/.

Andrei Fernández (Cutral-Có, Neuquén, 1983) is an independent curator, consultant and researcher. She has curated exhibitions in museums, galleries and artist-run spaces in Argentina, Germany, Paraguay, Portugal, Spain and the UK. She curated the project “La escucha y los vientos” presented in 2020 at the Berlin ifa-Galerie, and in 2021 at the Salta Museo de Bellas Artes and the Museo del Barro/Fundación Migliorisi in Asunción. She curated the 110th Salón Nacional de Artes Visuales del Palais de Glace organised by Argentina’s Ministerio de Cultura (2022). In 2023 she was in residence as a curator at the Delfina Foundation in London, with a grant from the Programa Puentes sponsored by the Argentine embassy to the UK and the Anglo-Argentine Society. She is a member of the Unión Textiles Semillas, weavers, artists and activists from Northeast Argentina, and, as such, works with the 99 Questions programme at the Humboldt Forum under the direction of Michael Dieminger. Together with the Wichi weavers collective, she works with the Cecilia Brunson Projects Gallery and community cultural projects in northern Salta. She is a member of FACT, the Fundación para el Arte Contemporáneo de Tucumán.

Claudia Alarcón’s work was featured in the 60th International Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere in 2024. In December 2022, Claudia Alarcón became the first indigenous woman to be awarded a National Salon of Visual Arts prize by the Ministry of Culture in Argentina. She was also awarded the Ama Amoedo Acquisition Prize at Pinta Miami in 2022, and her work is held in the collections of the Museu de arte de São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand (MASP), the MALBA Collection in Buenos Aires, the Denver Art Museum, Colorado, and the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minnesota.

Andrei Fernández, "Silät. The flickering of fabric." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/silat-le-cillement-du-tissu/. Accessed 26 January 2026