Research

Installation view of Noria Mabasa: Shaping Dreams (2022) at the Villa-Legodi Centre for Sculpture at NIROX Sculpture Park. Photo: Lucky Lekalakala. Courtesy of the Centre and !KAURU Contemporary Art from Africa

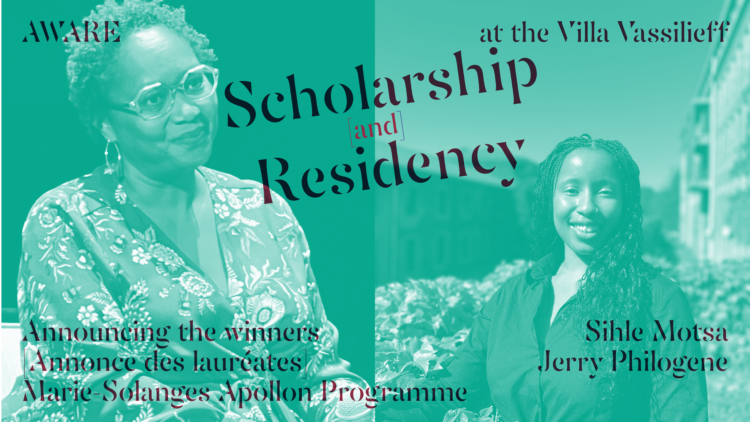

The following research project developed by Sihle Motsa as the recipient of the Marie-Solanges Apollon Scholarship looks at the mythologies generated by KwaZulu-Natal’s ecopolitical configuration through Noria Mabasa’s artistic lens. N. Mabasa’s sculptural works, Carnage I and Carnage II, were created as a meditation of the ecological turmoil that had gripped the province of KwaZulu-Natal, which in 1987 faced harrowing devastation from torrential floods. According to S. Motsa, these works might be recognised as an astute reading of the sublime quality of violence and ecological degeneration in KwaZulu-Natal. N. Mabasa’s life and oeuvre serve as a pointed disavowal of narratives that confine African artistic expressions to the formal and the so-called ‘traditional’. N. Mabasa’s works evince the fact that African aesthetic traditions offer a vernacular that is dynamic and capable of contending with cataclysmic occurrences. As such this exposition of her work contends with the political and ecological scenes as they are explored by the artist, asking how N. Mabasa’s representations embody the cyclical nature of both violence and climate injustice.

Violence is endemic to KwaZulu-Natal. One might even surmise that violence is part of the political and historical makeup of the South African province, as its story is shaped by conquest, war, dispossession and colonial violence. In the early 20th century, KwaZulu-Natal, like other regions, experienced massacres sanctioned by the British colonial administration in response to civilian-led rebellions and protests, notably the 1906 Bambatha Rebellion. During this tragic event, over three thousand Zulu workers were killed by the state for resisting the implementation of a new poll tax. The 1970s and 1980s saw KwaZulu-Natal engulfed in civil and political unrest. An intense political rivalry developed between the African National Congress (ANC) and the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) amid the broader armed struggle against Apartheid, leading to a brutal campaign of counterinsurgency1. Despite the dawn of democracy, violence persisted in KwaZulu-Natal, firmly embedding itself in the province’s political and cultural psyche. Beyond its turbulent political history, KwaZulu-Natal is also the site of profound ecological turmoil. Located on the eastern coast of South Africa, the province is prone to heavy rainfall and flooding whose frequency is exacerbated by climate change. In April 2022, one such flood killed over four hundred inhabitants of the region – a death toll second only to that of the floods that wrecked the region in 1987 – and displaced many others, the majority of whom were women living in informal settlements.

Examining the work of artist Noria Mabasa (1938–) is pivotal at this juncture. N. Mabasa’s works, although often viewed through the purview of the dreamscape, offer a way to contend with the histories and politics of KwaZulu-Natal, and the social processes operant in the country more broadly. They represent a poignant example of how African aesthetic traditions speak the experiences of its peoples, giving life to the particularity of being in a political landscape characterised by social and economic exclusions. These aesthetic traditions appear as not atavistic but inherently imbued with an ecological awareness and spiritual consciousness. N. Mabasa’s clay sculptures, fashioned from wood, water and red clay sourced from the river, make her an artist who converses figuratively and artistically with her landscape and her community. Her practices resonate with the scene in which KwaZulu-Natal has been irrevocably shaped by the processes of colonialism and global capitalism. Her sculptural forms embody the intertwined experience of marginality faced by the majority of KwaZulu-Natal’s population. In scholar Mlondolozi Zondi’s stirring wording, N. Mabasa’s forms serve as “a mode of negotiating epigenetic memory”, as a way to reckon with the sublime face of political and ecological disorder and encode the experience using a Black artistic vernacular.2

“Noria the artist”, Thembinkosi Mabaso for SPEAK Magazine, Johannesburg (South Africa), October 1993, newspaper clipping

The artist was born Noria Muelwa Luvhimbi in Limpopo, South Africa’s northernmost state, in the village of Xigalo. As a young girl, N. Mabasa was subjected to patriarchal standards, performing chores in her rural village. She then left for Johannesburg to live with relatives. There, she met and married Jim Mabasa in 1954. The couple returned to Limpopo with their two children but they separated when she began having nightly visions and psychosomatic symptoms relating to her artistic calling. In these dreams, she encountered the figure of an old woman “with leprosy, no mouth and no nose”3 who haunted her for ten years. After a ritual healing, N. Mabasa resolved to keep the illness and the visions of the old woman at bay by giving in to her demands. She began sculpting figurines which she sold at the local market. This dialogue with the woman, whom N. Mabasa references as one of her guides,4 led to larger works and eventually to wood – wood that has since become closely identified with her artistic identity. She has acknowledged that it was chiefly her women ancestors who guided her towards sculpture, although she was initially hesitant due to its predominantly male-dominated culture establishing wood carving as the preserve of men5. In the Venda cosmogony and culture, men traditionally act as intermediaries with the spirits on behalf of the entire family, as women are not granted the authority to do so. However, N. Mabasa challenges the limits of this gendered order, demonstrating through her art that Venda women too can give the world a representational form.

Her own artistic journey is a consequence of communing with the spirits and attentively listening to their guidance. More than the profundity of the dream and its centrality in N. Mabasa’s practice, the time between the dream and the shaping of the clay reveals a deeply perceptive vision. Through thoughtful contemplation and rumination, this insight brings forth the gifts of the artist’s psyche. N. Mabasa’s first clay sculptures capture traditional Venda scenes, in which the day to day is imbued with symbolism. This period mainly featured portraits, each with a resounding dignity or pathos – a sense of intrigue and tenderness. N. Mabasa’s women figures in particular intimated a reverence that did not romanticise their hardships but located them as important vectors within the community and within the sphere of social, spiritual and political reproduction6.

In her series Carnage (1987/88), N. Mabasa skilfully navigates realms beyond the physical and delves into the political constructs that shape and confine racialised and gendered existence. Carnage comprises four wood sculptures that serve as a poignant reflection of the gender dynamics within her society, influenced by her personal experiences. In Carnage I, N. Mabasa portrays a scene of communal embrace where human figures engage in dialogue with various animals such as cows, sheep and dogs within an intimate, circular space. This setting symbolises a world where animals play a crucial role in facilitating communication between people and the spiritual realm, emphasising their significance and reverence. Sculpted in the traditional style of the region, using unprocessed timber that incorporates natural elements of the tree, the work embodies a rhythmic flow. This flow mirrors the movement of diverse elements through the artist’s own life and resonates within the creative and political landscape that shapes her practice.

Noria Mabasa, Carnage II, 1988, fig tree wood, 80 x 250 x 200 cm

Noria Mabasa, The Flood, 2002, single section of a giant sycamore fig tree, 154 x 69 x 43 cm

The figures of Carnage II present a more embattled scene. Fluid forms are entangled as they attempt to retrieve a body from the jaws of a crocodile. Smooth wood figures glide into each other in a manner that betrays the fraught scene, urging us to face the dual symbolism implied. The image conjures a watery world where water allows for a lightness of body and being, but can also be a source of profound danger, violence and sinister allure. We are reminded of the repeated flooding in KwaZulu-Natal, reflecting the duality present in N. Mabasa’s sculptural scenes.

Made from a giant section of a single sycamore tree, The Flood (2002) renders a scene where bodies are stacked rhythmically one atop of another in an image of poignant chaos. The angles at which the bodies lie suggest a rupture in the natural order as they appear to be ascending, or at the very least in supplication – entreating the heavens for a reprieve. The piece similarly reflects both political and ecological turmoil that peaked in 1987 in KwaZulu-Natal. The upheaval rendered in this artwork, and even its name, has a metaphoric resonance in keeping with N. Mabasa’s perceptiveness.

Noria Mabasa, Tsanwani, 2004, clay, 30 x 35 x 53 cm, installation view of Noria Mabasa: Shaping Dreams (2022) at the Villa-Legodi Centre for Sculpture at NIROX Sculpture Park, © Photo: Lucky Lekalakala. Courtesy of the Centre and !KAURU Contemporary Art from Africa

Installation view of Noria Mabasa: Shaping Dreams (2022) at the Villa-Legodi Centre for Sculpture at NIROX Sculpture Park. Photo: Lucky Lekalakala. Courtesy of the Centre and !KAURU Contemporary Art from Africa

Installation view of Noria Mabasa: Shaping Dreams (2022) at the Villa-Legodi Centre for Sculpture at NIROX Sculpture Park. Photo: Lucky Lekalakala. Courtesy of the Centre and !KAURU Contemporary Art from Africa

N. Mabasa’s choice of the sculptural medium positions her as an important figure within a tradition that burgeoned beyond the reaches of a pervasive colonial mandate. As such, her work represents more than a pure indigenous expression; it stands as a deliberate rejection of Western colonialism’s pervasive reach. It serves as a clear disavowal of co-option and appropriation, dedicating itself instead to crafting an artistic lexicon that acknowledges its deep connection to the world in all its ecological, psychological and emotional dimensions. Over the years, N. Mabasa has revealed herself to be a strong and independent voice. Despite her self-excommunication from the white-run art spaces of the Apartheid era and a gendered marginalisation, she has continued to carve the South African political and ecological rhythms into her wooden figures. From May to June 2022, the artist significantly benefited from a residency and an exhibition at NIROX’s Residency Studio in South Africa, followed by a subsequent retrospective, Noria Mabasa: Shaping Dreams, at the Villa-Legodi Centre for Sculpture from October to November 2022, in collaboration with !KAURU Contemporary Art from Africa and the Vhutsila Arts and Craft Centre. In 2023 she was conferred with an honorary doctorate in art and design by the University of Johannesburg, a feat that speaks to how her work has quietly but powerfully shaped the South African artistic landscape.

In 2024 N. Mabasa continues to work from her home in the Limpopo province, where her homestead is open to artists, researchers, tourists and those simply spurred on by curiosity. Her home is a beacon of artistic pedagogy, where she continues to teach those interested in the importance of being and place, the history of South Africa, its political and social idiosyncrasies and how these might be illuminated by the artist’s hand.

Johnston Alexander, “Politics and Violence in KwaZulu Natal,” Terrorism and Political Violence, vol. 8, no. 4, 1996, pp. 78 – 107.

2

Mlondolozi Zondi, “‘An Impossible Form’: The Absence That Keeps on Giving,” Liquid Blackness, vol. 8, no. 1, 2024, pp. 28.

3

South African Department of Arts and Culture, (2021) “Noria Mabasa –Sculptor of Dreams”, ArtFundi Tech, pp. 14.

4

South African Department of Arts and Culture, (2021) “Noria Mabasa –Sculptor of Dreams”, ArtFundi Tech, pp. 9..

5

Thembinkosi Mabaso, (1993) “Noria the Artist”, Speak, pp. 10.

6

Noria Mabasa famously depicted the Women’s March to the Union Buildings in 1956 where tens of thousands of South African women gathered in protest of the Apartheid government’s oppressive pass laws.

Sihle Motsa is an art historian and art practitioner. Holding a master’s degree in art history from the University of the Witwatersrand, she has worked as a researcher, writer and curator of exhibitions on Black material cultures, ecological vernaculars and Black women’s artistic practices. She is pursuing a second master’s degree with the Department of Historical Studies at the University of Cape Town.

Sihle Motsa, "A Violent Sublime: Noria Mabasa’s Ecological Reckoning." In Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions magazine, . URL : https://awarewomenartists.com/en/magazine/un-violent-sublime-leco-politisme-de-noria-mabasa/. Accessed 17 January 2026